We know that museums are an archive of memory. Not just of the life of the works and their artists but also an archive of the life of the institutions. Small and large museums have at times been tasked with responding to contemporary social problems. Today, our interest is in knowing whether this social aspect linked to migration processes remains, creating hospitable spaces where people can meet. Museums that can be homes.

Below you can read extracts from different conversations and meetings on hospitality and the role of cultural institutions as meeting spaces. These reflections were prompted by a series of questions that emerged out of dialogues between different specialists from fields such as museum curating, anthropology, cultural management and production, and the creation of art.

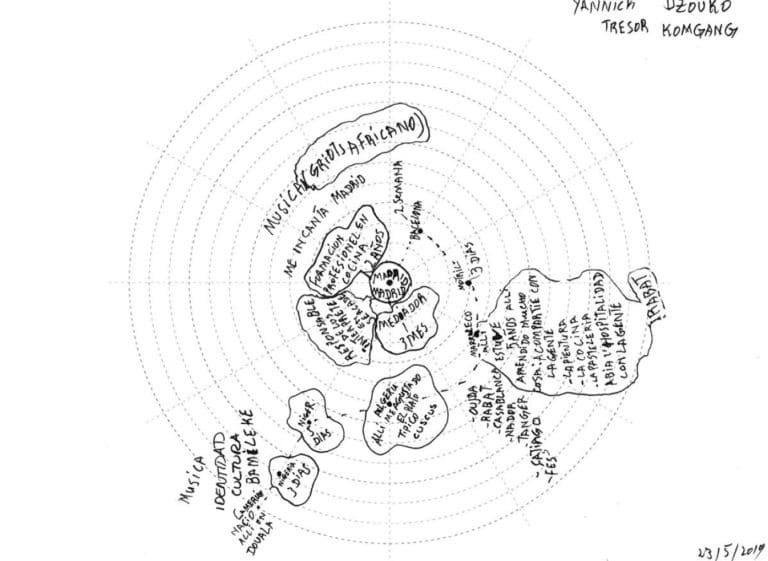

Yannick Tresor’s map

How do we understand hospitality?

Susana Moliner (Grigri Project): I have worked on community cultural projects for some time. In many of them we have proposed different themes and last year we reflected on the idea of hospitality. Within this proposed space for reflection, the philosopher Marina Garcés has given us three essential terms to understand what hospitality might entail: “arrive”, “welcome” and “decide”. In an extract from our interview with Marina, she said that it was crucial to understand hospitality as a set of relations and practices that cannot be thought about in isolation. Rather, they must be considered collective practices that weave fabrics because they are counterweights to limits, borders, border spaces and voids, but also to the mental, cultural, religious, bodily and racial voids that challenge us all the time.

Hospitality is not just about opening the possibility, but of that possibility making us look at life and our lives in a different way. It is a reciprocal exercise, not only for the person arriving and the person who opens up, but because there is a transformation regarding the point or moment at which the other will become us, and in my view that is the complex part.

In parallel, around the questions relating to hospitality, we work in a practical manner with the idea of vital pathways and maps. To tackle the issue, we proposed using concentric circles where the important thing for everyone was that the centre that unites us should be the city of Madrid. Here is one of the proposals from Yannick Tresor, from Cameroon. Yannick has been in Madrid for two years and it took him nearly four years to get here. He managed to cross the border and then caught a small boat in Morocco, finally arriving in Almería. The idea behind the creation of this map was not to share the difficulty and the trauma of the endeavour, but to share all the lessons and give visibility to all these spaces, experiences and people that made him feel at home

Xirou Xiao (Artista, educadora e investigadora): In my case, I’ve been living in Spain for more than seven years. Here I work as an artist, educator and mediator and I’d like to add to the conversation by sharing what home means to me. Two years ago, in China, at home with my cousin and my grandmother, I asked myself the same question leading to the following reflection that would form part of the Como la casa mía project.

“At times I feel like a plant with no roots that flies in the wind and sows its seeds where it falls. Home is the home of my body. My body makes my house a home even if it’s not always very neat. My house, where there’s affection in the air, dancing in silence and the tears, no, those drops behind our eyelashes flowing, and where time escapes ceaselessly.”

In terms of hospitality, at first I didn’t understand the word. It was very exotic. So I looked up the meaning and, with the help of Google, discovered that it’s a quality of welcoming guests with friendliness and generosity. After reading the official meaning of hospitality, it’s not a word that represents me. I don’t belong to this word. What is it talking about? From what position do they speak of this hospitality? In the end I’m the guest, the other and the stranger. After that, I looked a little further and in the debate on hospitality found two specific currents. On the one hand, there is the idea that hospitality serves as an ideological instrument to control the foreigner, while the other current talks about hospitality as a system for the exchange of goods, skills and favours, with the emphasis on social legitimacy.

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza

Marco Godoy (Artista visual): In my artistic work, I’m especially interested in the issue of power, how it’s structured, how it’s maintained and how this question pervades places, disciplines and relationships. In this sense and in relation to what we’re discussing, I would like to ask a few questions. What direction does hospitality have? What hierarchical directions are there between the giver and recipient? How is hospitality geared towards an encounter between people who share or exchange as a gesture of empathy with each of their positions?

It would be necessary to put into practice a hospitality that, for example, is not affected by social class or gender relations, which are limitations that are very present when it comes to visiting an institution or feeling part of it. Don’t you think so? I think, in the end, all of these questions are found to be implicit before you reach the space and that prevents a stranger to this space from really being part of it.

Are museums spaces of hospitality?

What is the response of art to the different social crises?

Sara Torres (Researcher): Let’s take the word hospitality. What is the need? Can we verbalise this need that the museum is looking to satisfy through hospitality? I have always understood the arts as being in the public domain, part of the commons. If art isn’t for everyone, it’s not art because we’re talking about a luxury. We’re starting from the basis that art is a human need and, as a human need, I don’t need a museum to come and give it to me.

Art is present in lots of ways in many moments of our lives. So then, the museum… how does it contribute? And if we go back to the word hospitality, is it a tool or not?

Marco Godoy (Artist): I think that in a collection with a journey over time like that of the Museo Thyssen, in the end all these images are a way of helping us to be and to understand the complexity of our contemporaneity, because lots of contexts and works have been repeated, haven’t they? There is a nice moment in the French Revolution when they collected all of these works from the aristocracy and asked, “What should we do with them?” Some said, “We should burn them as a symbol of tradition, we have to invent a new world.” Others argued for placing them on display for everyone, regardless of social class, gender or origin. Then the Louvre was created and its mission was for every French man and woman to visit it at least once in their life, because part of the experience as a citizen was to see these works. Of course, the images themselves, in reality, do not have this capacity until you activate it. You give them life because suddenly they seem contemporary.

So, what can I do to make sure, as part of my experience as a visitor, that when I leave the museum these activated images remain with me? Of course, we also have to understand that society is changing rapidly. So, maybe it’s not so much about looking at the collection as looking at society. So I wonder, what’s the point of negotiation? What is the meeting point between images and experiences? I always believe that the work of the images has a lot to do with weaving an experience, a time, an image in which you as a spectator can develop this type of relationship with the artwork.

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza

Rufino Ferreras (Education Area of the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza): The question is where we position ourselves. I think it is necessary not only to look at it from an art history perspective. The history of art is just another tool. We should look from a contemporary perspective and everything that comes with it. The power to look at the past from today brings me to that apocryphal quote attributed to Mark Twain: “History doesn’t repeat itself but it rhymes.” Of course, we can talk about the past and highlight the problems of the present through images from centuries ago, because human beings have always had the same problems in different contexts, at different times and I think that’s the way for the narrative to be reversed and make museums relevant to 21st-century societies. There is no sense in approaching the works only through the narratives of the past with a society that is asking us for narratives of the future.

Susana Moliner (Grigri Project): Make it possible for the collection to be a polyhedron, if I’m saying that correctly, that has many prisms and can generate these necessary narratives.

Juan Ángel López Manzanares (curator and chief content officer at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza): From everything we’re talking about, I think that one of our fields of work might be that of building experiences and relationships with people like a rhizome; a root that extends horizontally but that has no centre. I believe that a museum must lose a lot if it wants to be hospitable in the strongest sense of the word. It has to decentralise, admit that there are many different narratives, that there are many different people, and develop a plural, fragmented discourse, even though museums don’t usually do this.

Also in line with this conversation, I would like to tell you about one of the most revealing moments of my career. It happened last year, when I was attending the ICOM International Conference in Kyoto. There was a debate about the new definition of the museum. Even though it didn’t pass, largely due to the opposition of the art museums and traditional ideology against anthropology or natural science museums, it nonetheless outlined the museum of the future. There were various fundamental ideas debated with which I identify quite closely: The need for the museum to respond to the challenges of the time (climate change, poverty, social and cultural inequality, etc.); its active role as a forum of social debate and a creator of social well-being (and not only as a temple for the contemplation of beauty for a select few); its inclusiveness, open to the communities around it; its critical nature, which promotes different narratives against a single narrative imposed by the management of the museums.

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza

How are museums questioning audiences?

How would we like them to be?

How could they satisfy social demands?

How can they create networks and build support communities?

How can the museum be a home?

Ana Gómez (Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza): Museums are born as spaces to conserve and display collections; as institutions that legitimise knowledge. They therefore become a space of power. Spaces to view and admire works. These museums are created following the structures of the past and within globalised, capitalist systems of logic. On the one hand, the museums of today respond to these demands, but they have the opportunity to create more inclusive and social spaces. But how can we create a network of relations with those who don’t visit the museum? How can we listen to them and build this experience? I think, basically, the important thing is to focus on listening to the other and creating universal experiences and narratives, issues and questions that unite us rather than separate us.

Sara Torres (Researcher): And with the only mobilisation strategy with which I don’t have a conflict, which is that which comes from outside. The idea that there is a social demand. We all know that changing internal structures is very difficult from our own quarters. But if there is a social demand and it’s strong and robust, then the museum has no choice.

Marco Godoy (Artist): Returning to hospitality, which continues to cause the same problems for me. I’ve spent a while searching for the looking glass. We’ve been asking ourselves how to make the museum more hospitable, but I wanted to ask: Have we asked the communities themselves how they would be more comfortable rather than asking ourselves? How can we escape our own skin and approach these communities?

Patricia Alonso (curator, Museo Nacional de Antropología): Here at the Museo de Antropología we’re rethinking our own institution to turn it on its head. For several years we have been attempting to change things with projects where we rethink the collections on the basis of the participation of the source communities. We have come up with four temporary exhibitions in which this participation is key: Tigua: Art from the centre of the world, curated together with Alfredo Toaquiza, one of the outstanding Tigua painters; Rio somos nós! The Community Museums of Río de Janeiro and the Shift to Decolonialism, curated by the professionals of eight participating community museums; and two more exhibitions, the first focused on Ecuadorian migrants and the second on the Senegalese community in Madrid. In these exhibitions, the museum offers resources and advice, but it is the migrants who participate in the project who make the decisions about the exhibition and prepare the discourse around it. They are the ones who decide what they’re going to tell us about themselves, about their country of origin and about their experiences in Spain.

Rufino Ferreras (Education Area of the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza): I would like to finish my contribution to these sessions by suggesting that perhaps museums themselves, in a sort of neo-liberal shift, have defended the idea of social institutions where reality sees the person as a customer and not as a stakeholder who forms part of something, of a home. And along these lines, we are always talking about the rights of others, those who have no access to museums, but we never realise they have a right not to want to come and museums also have to defend that right. Defend the right of the people who don’t want to come to discern and reflect on the role of the museum in contemporary society.

Susana Moliner (Grigri Project): I think that’s a very relevant reflection. Often, these types of proposals focus on including other voices and integrating other communities in the question. We question neighbours, migrants, women, people from the neighbourhood, etc., and the first response is that perhaps they’re not interested, that they don’t feel any sense of belonging and nor do they feel challenged. In this regard, I think it’s interesting to approach it more as a need of the institution itself to learn and to look at itself from another perspective, to decentre. A museum that grows from these perspectives, to learn and to give visibility to these other stories hidden within their works.

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza

“Human beings are closeness and shelter. It’s not a house that’s a shelter, rather it’s human beings, their way of being constitutes shelter”

The Intimate Resistance, Josep María Esquirol.

“Human beings are closeness and shelter. It’s not a house that’s a shelter, rather it’s human beings, their way of being constitutes shelter”

The Intimate Resistance, Josep María Esquirol.