To New York

“In a way I’m sort of limited to Sundays in New York. There’s too much traffic during the week. I work from a tripod with a 4 x 5 camera. I get set up and somebody pulls up and parks a car right in front of me. So I really have to photograph on Sundays. It’s impossible any other time. I wait for a good Sunday, when it looks like a really beautiful day with sun and fluffy clouds. I have to drop everything and go out to photograph because I may not get another Sunday like that for months.” Richard Estes

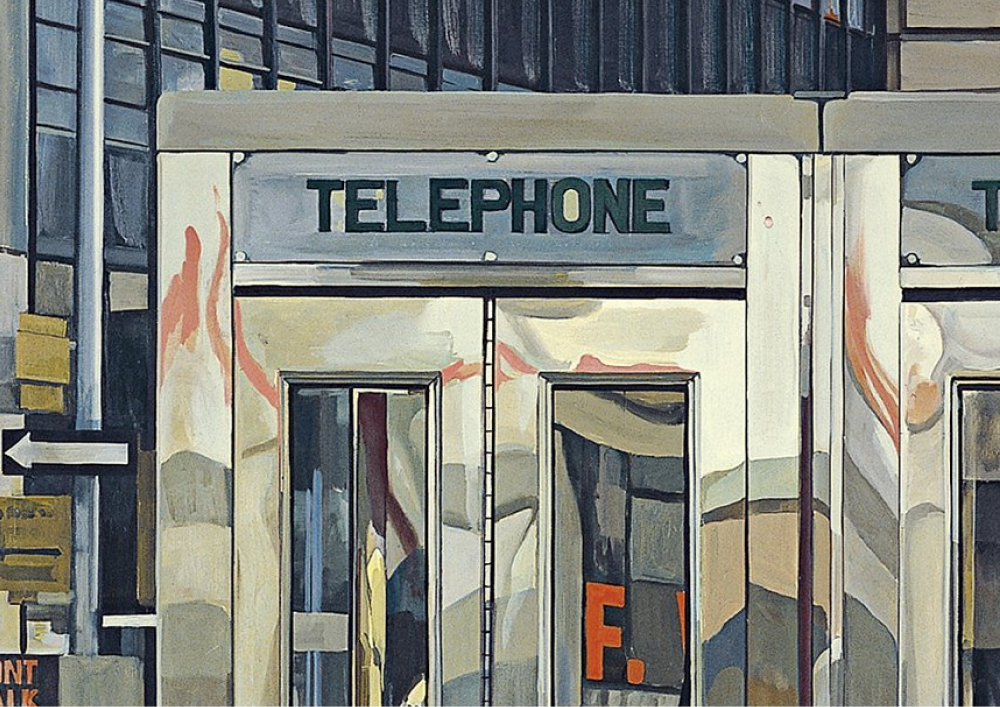

Artist Richard Estes took several photographs of phone boxes at the intersection of Broadway, Sixth Avenue and 34th Street, which he combined and transformed into a painting titled Telephone Booths (1967).

Richard Estes

Telephone Booths, 1967

Acrylic on masonite. 122 x 175.3 cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

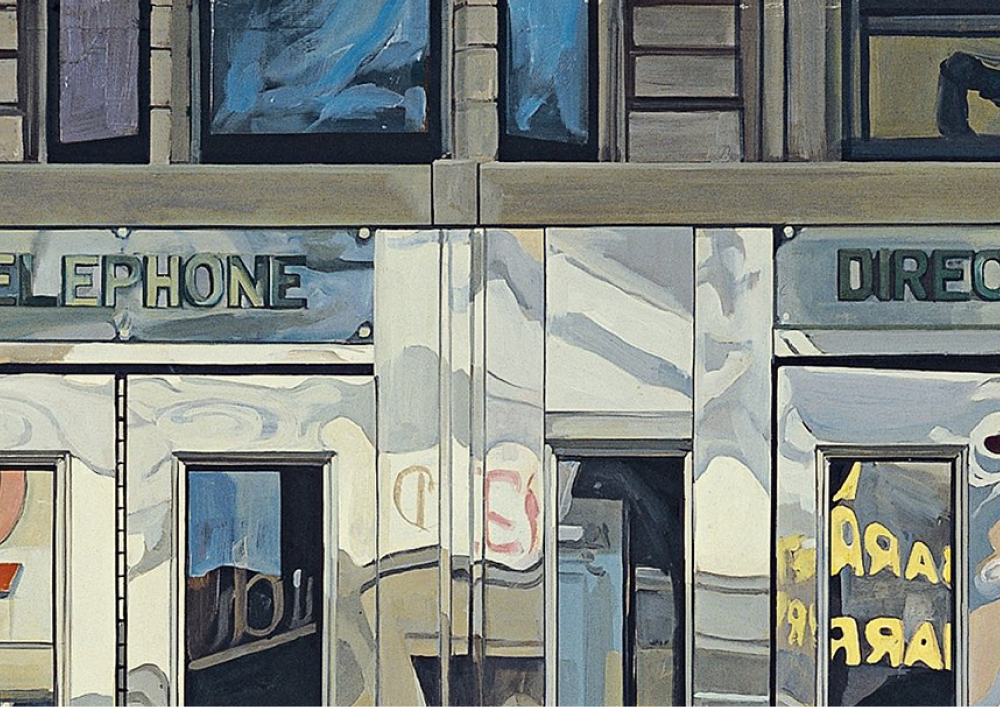

Richard Estes

Telephone Booths (close-ups), 1967

Acrylic on masonite. 122 x 175.3 cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Under the label of photorealism, Estes’s work conceals a complex, confusing city. For this reason, when we look at the composition, we see glass panes that are mirrors, mirrors that do not reflect, some recognisable reflections and other misleading ones, sparks which our mind struggles to interpret.

Bewildered by the distorted surfaces of the booths and dazed by the intense photorealistic effect, we believe we are looking at truth when in fact we are not. We are facing a discourse of the real where, as Italo Calvino wrote in Invisible Cities, “The eye does not see things but images of things that mean other things”, and where “your gaze scans the streets as if they were written pages: the city says everything you must think, makes you repeat her discourse, and while you believe you are visiting Tamara you are only recording the names with which she defines herself and all her parts”.

The picture contains infinite signs that point to a particular time and place. For instance, we can make out a yellow cab, we see several people with their backs turned to us, and we recognise the buildings looming up behind us, like Macy’s department store or the American fast-food chain Nedick’s.

Rather than giving us answers, it seems the painter wants to ask us questions. We are flustered and invited to understand those incomprehensible symbols. As “there is no language without deceit”, each of us must detect and avoid the trap, the great lie of the city, and project our truths onto it; we must strive to lift our critical gaze above this city made of signs until we glimpse our silhouette in the distorted reflection of its booths.

(1) Various taxis on the streets of New York, 1967

(2) Macy’s department store in New York, 1967

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza