To the city that was a woman

“No one knew me, no one looked at me, no one found fault with me; I was an atom lost in that immense crowd.” George Sand

The Psyche Mirror (1876) is a work that portrays feminine intimacy from the painter’s own experience. Berthe Morisot created it in the bedroom of her Paris home on rue de Guichard. Like the works of her Impressionist contemporaries, most of Morisot’s pictures were set in rooms and domestic interiors. She painted her immediate surroundings because, in the 19th-century mentality, there was a clear separation between the public and private spheres, and a bourgeois woman like her could not freely enter the public space whenever she pleased. That division was based on social status, but also on gender: while men enjoyed the new urban settings, women’s activities were limited to the domestic arena.

Berthe Morisot

The Psyche Mirror, 1876

Oil on canvas, 65 x 54 cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

By that time, flânerie—strolling aimlessly through the city, stopping to observe it (amid the crowds) and having time to narrate it—had become an exclusively male privilege, but it was also an absolutely necessary exercise for any self-respecting modern artist. Marie Bashkirtseff, a French painter of Ukrainian heritage and a contemporary of Morisot’s, expressed this in her notes: “What I long for is the freedom of going about alone, of coming and going, of sitting in the seats of the Tuileries […], of walking about old streets at night; that’s what I long for, and that’s the freedom without which one cannot become a real artist.”

Marie Bashkirtseff

In the Studio, 1881

Oil on canvas, 188 x 154 cm

Dnipropetrovsk State Art Museum, Ukraine

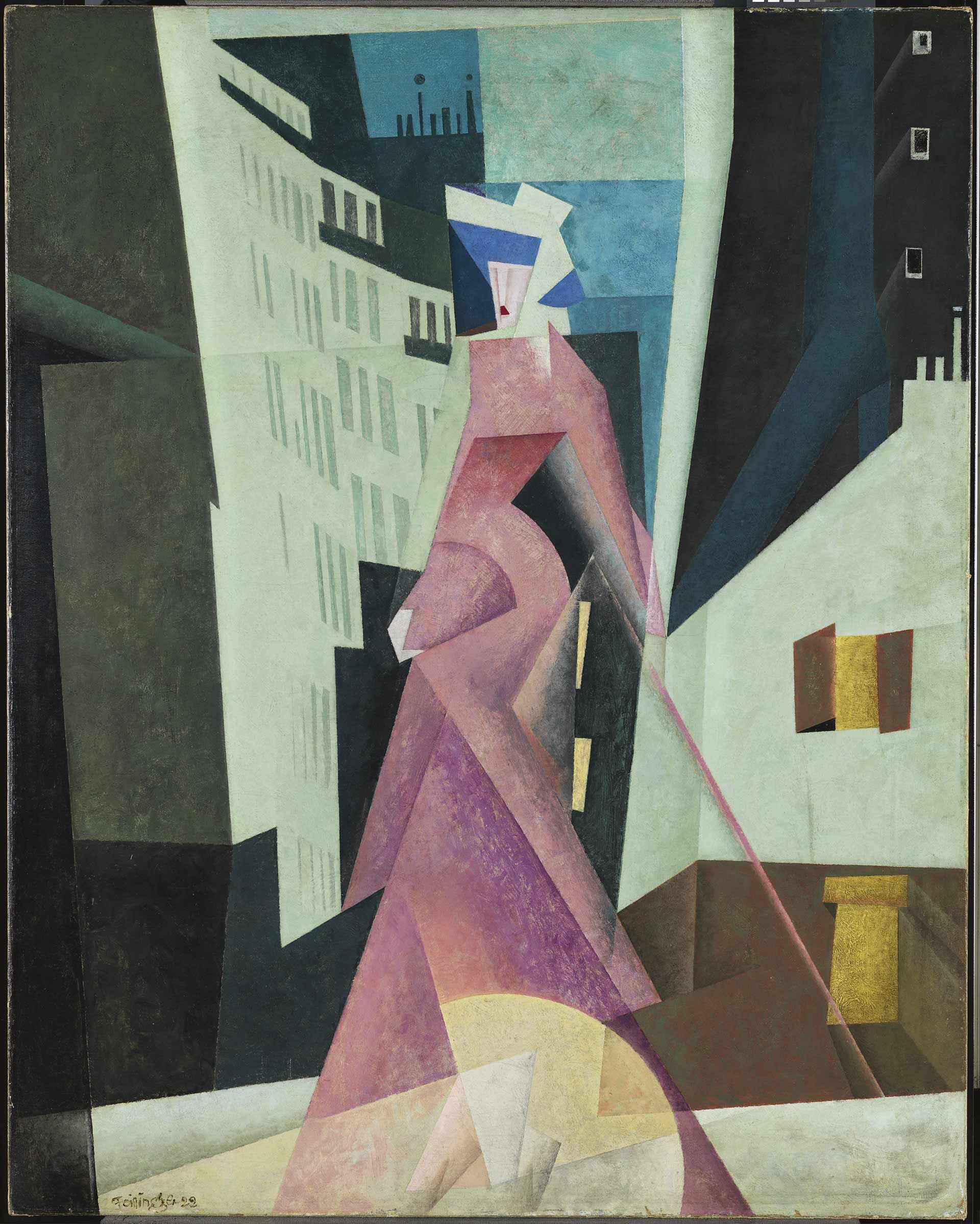

Yet this new social order could not stop women from filling the cities, out of necessity or a determination to defy conventional gender roles. In fact, their presence in urban settings was the great novelty of the principal modern cities. However, the representations, depictions and accounts that have shaped our collective imagery do not portray them as strollers or passers-by—in other words, as flâneuses—because women were denied the status of subjects. Woman was the observed and narrated object, the fleeting body that sparked the imagination and desire of the flâneur. This is how she appears in the dreamy recollection of Paris that Lyonel Feininger painted in Weimar. She is the fugitive who inspired the founding of the city of Zobeida, as described by Italo Calvino: “Men of various nations had an identical dream. They saw a woman running at night through an unknown city; she was seen from behind, with long hair, and she was naked. They dreamed of pursuing her.”

Despite social constraints, there was a female flânerie or flâneuserie of which little has been told. All sorts of rebellious walks through London, Berlin, Madrid, Saint Petersburg and other cities inspired and continue to inspire many women to explore and inhabit the urban space in a different way.

However, in the early decades of the 20th century, bustling Paris may have been the city that offered women more new and unprecedented opportunities than any other: anonymity, employment, uniquely female settings… At least this was true for what Shari Benstock called the “women of the Left Bank”, a motley community of self-sufficient urban ladies who came from near and far and settled in the City of Light’s charming sixth arrondissement.

French, German, English and American expatriates were united by Paris and the chance to live their own lives which they city offered them. The beautiful Natalie Barney always felt that Paris was “the only city where you can live and express yourself as you please”.

Lyonel Feininger

The Lady in Mauve, 1922

Oil on canvas. 100.5 x 80.5 cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Underwood & Underwood, New York City (photographer)

Party delegation en route to Paris to seek admission into the International Woman’s Suffrage Alliance, 1926

Eugène Atget

Eclipse (Paris), 1911

Library of Congress

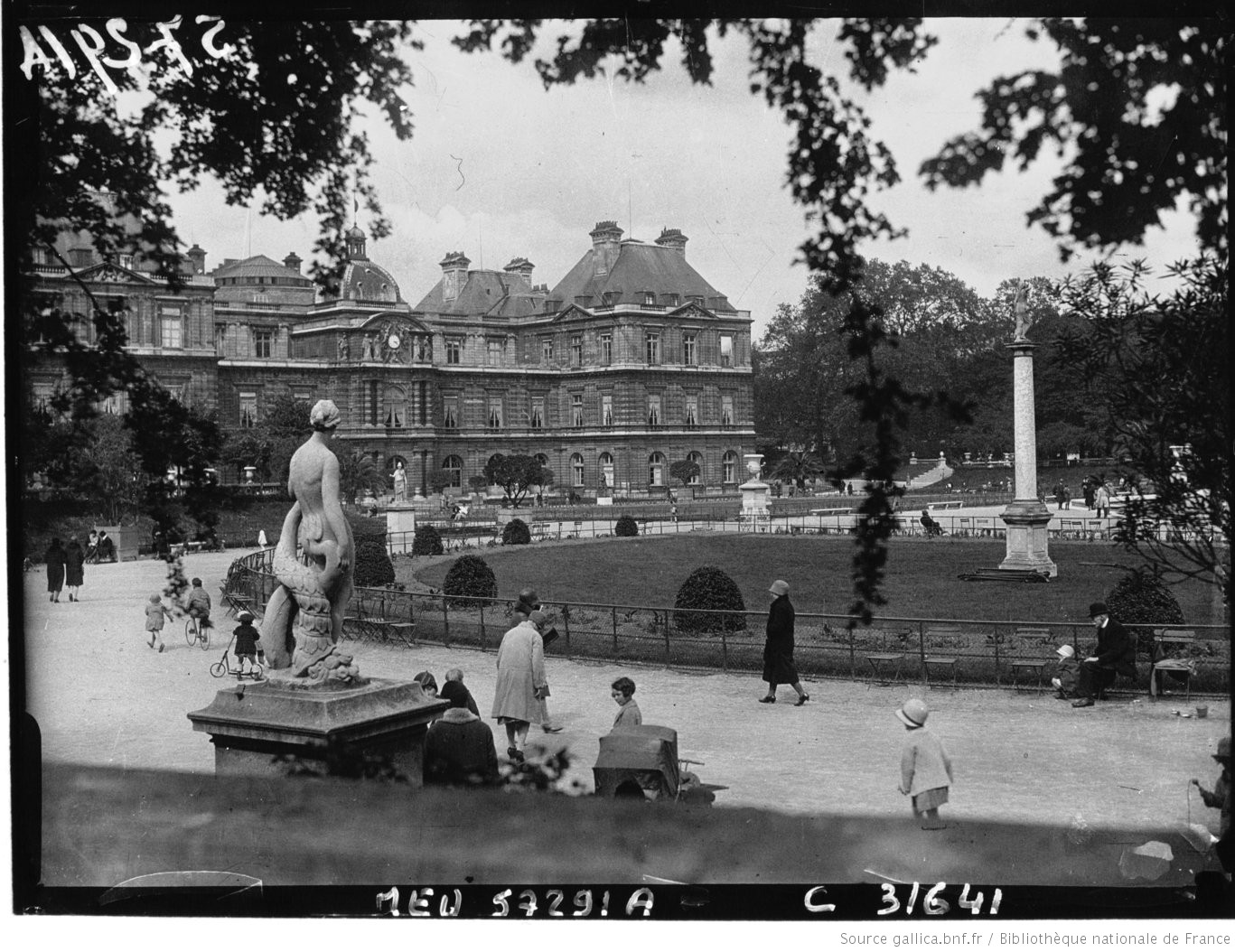

Agence de presse Meurisse

Luxembourg Gardens (Odéon, 6th Arrondissement, Paris), 1928

Bibliothèque nationale de France

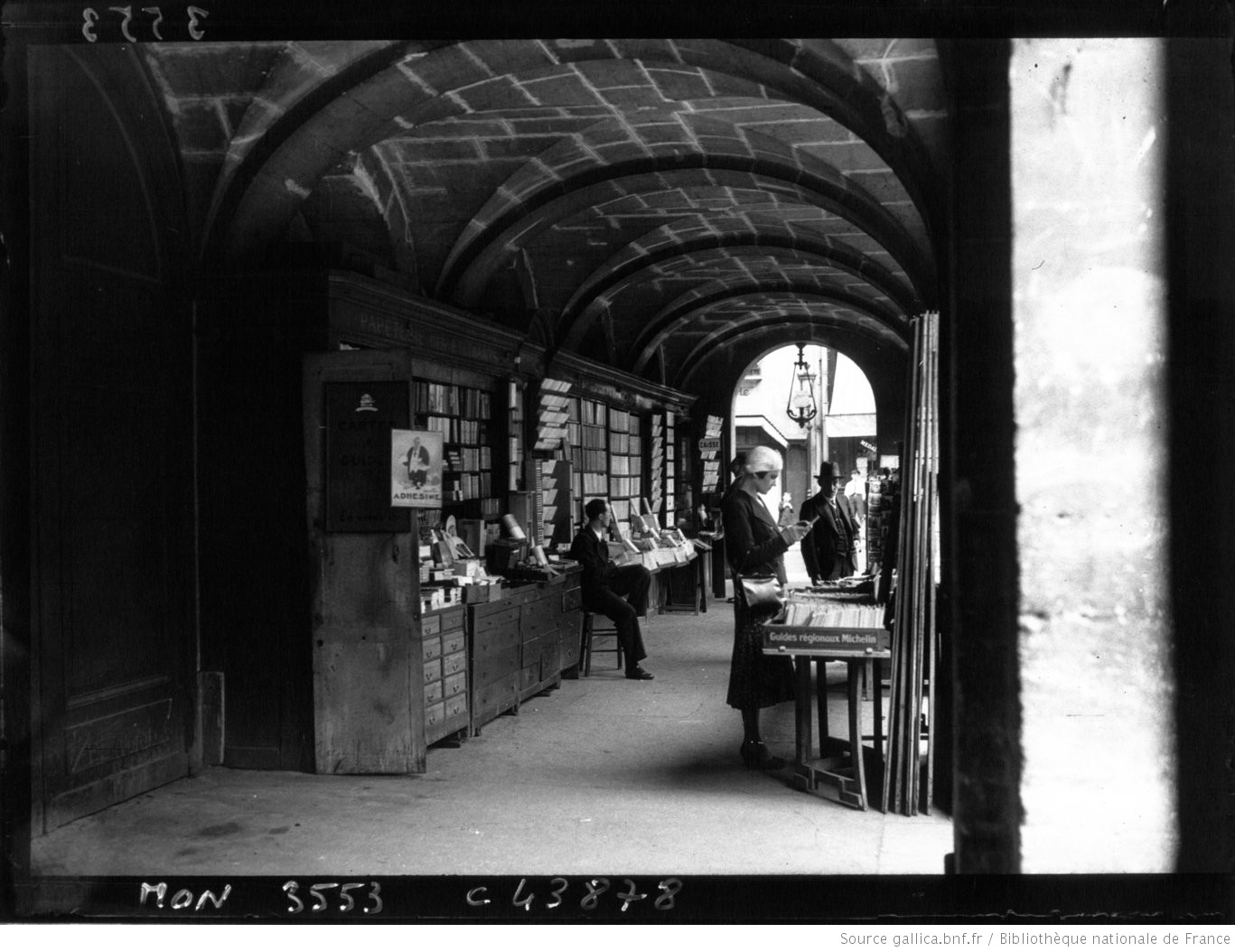

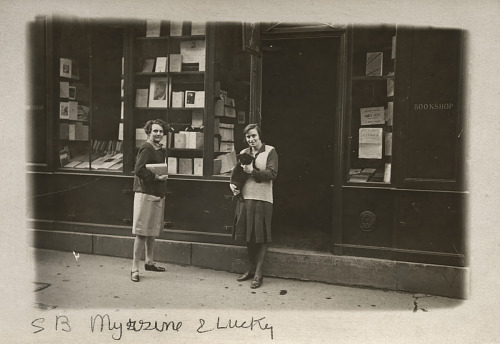

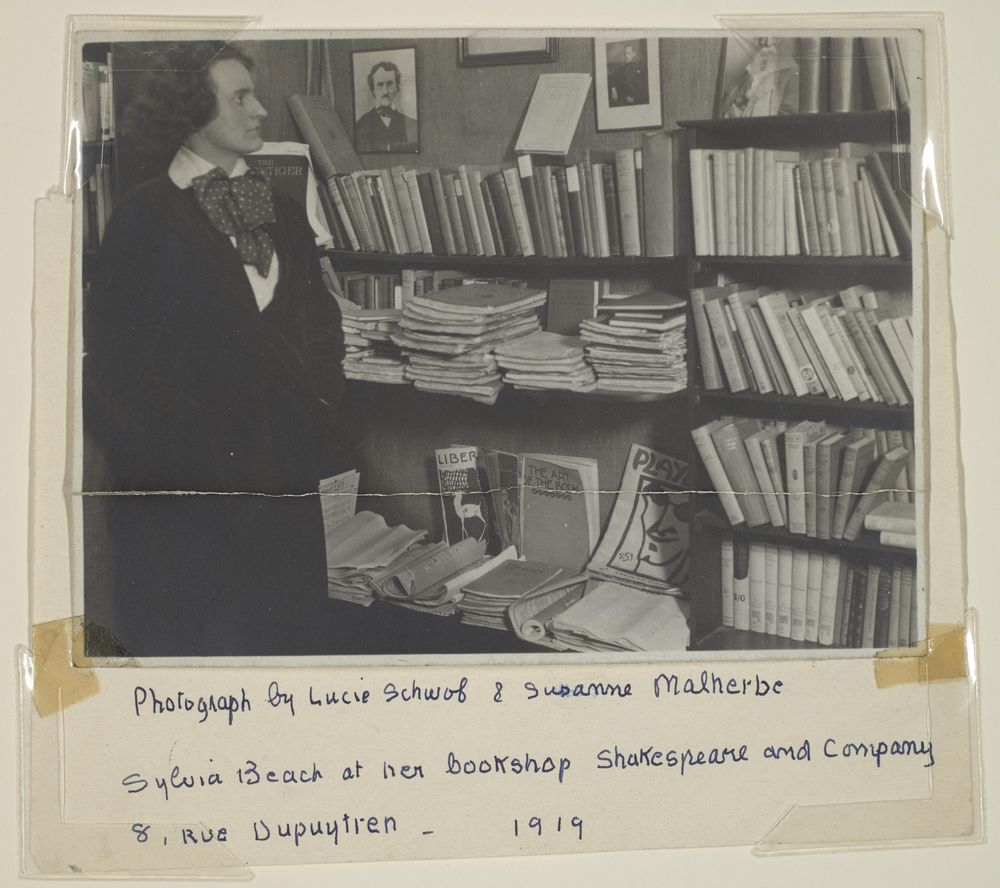

Not all of them practised flânerie in the strict sense of narrating the experience of roaming the city streets. But these female writers, publishers, photographers, painters, journalists and booksellers created three Parisian milieus that changed the city’s cultural scene: rue de l’Odéon, where Adrienne Monnier and Sylvia Beach, the first to publish James Joyce’s Ulysses, opened their respective bookshops, La Maison des Amis des Livres and Shakespeare & Co., the hubs of avant-garde English and French literature; Natalie Barney’s Temple of Friendship in rue Jacob, where Paris’s lesbian community gathered; and the fascinating apartment in rue des Fleurus owned by “literary Cubist” Gertrude Stein, where the cream of French avant-garde society began to come on Saturdays at any hour to admire her Matisse and Cézanne paintings.

Mondial Photo-Presse

Odéon, bookshop gallery, 1932

Bibliothèque nationale de France

Sylvia Beach, Myrsine Moschos and Lucky, 1924

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Claude Cahun

Sylvia Beach at rue Dupuytren, 1919

Princeton University Library

In one way or another, each left a record of their communal life in what the writer Colette called the “City of Love”, a contravention of the urban narrative that cost Stein the rejection of several friends when she published her successful chronicle of the artistic avant-garde in Paris, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933). Stein’s friend Janet Flanner highlighted that narrative in her fortnightly column for The New Yorker, titled “Letter from Paris”, in which the insightful American journalist gave an eyewitness account of Parisian modernity. Also present was the photographer Berenice Abbott, who began to portray European avant-garde intellectuals at Man Ray’s Paris studio and whose images were permanently displayed in Sylvia Beach’s bookshop. Following Eugène Atget’s example in Paris, she returned to New York in 1929 and spent nearly a decade recording the changes in the city’s physiognomy.

Sylvia Beach

Marie Laurencin, n.d.

Bibliothèque Marguerite Durand

Natalie Barney, Janet Flanner and Djuna Barnes, circa 1925

Sylvia Beach and Adrienne Monnier, circa 1938

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

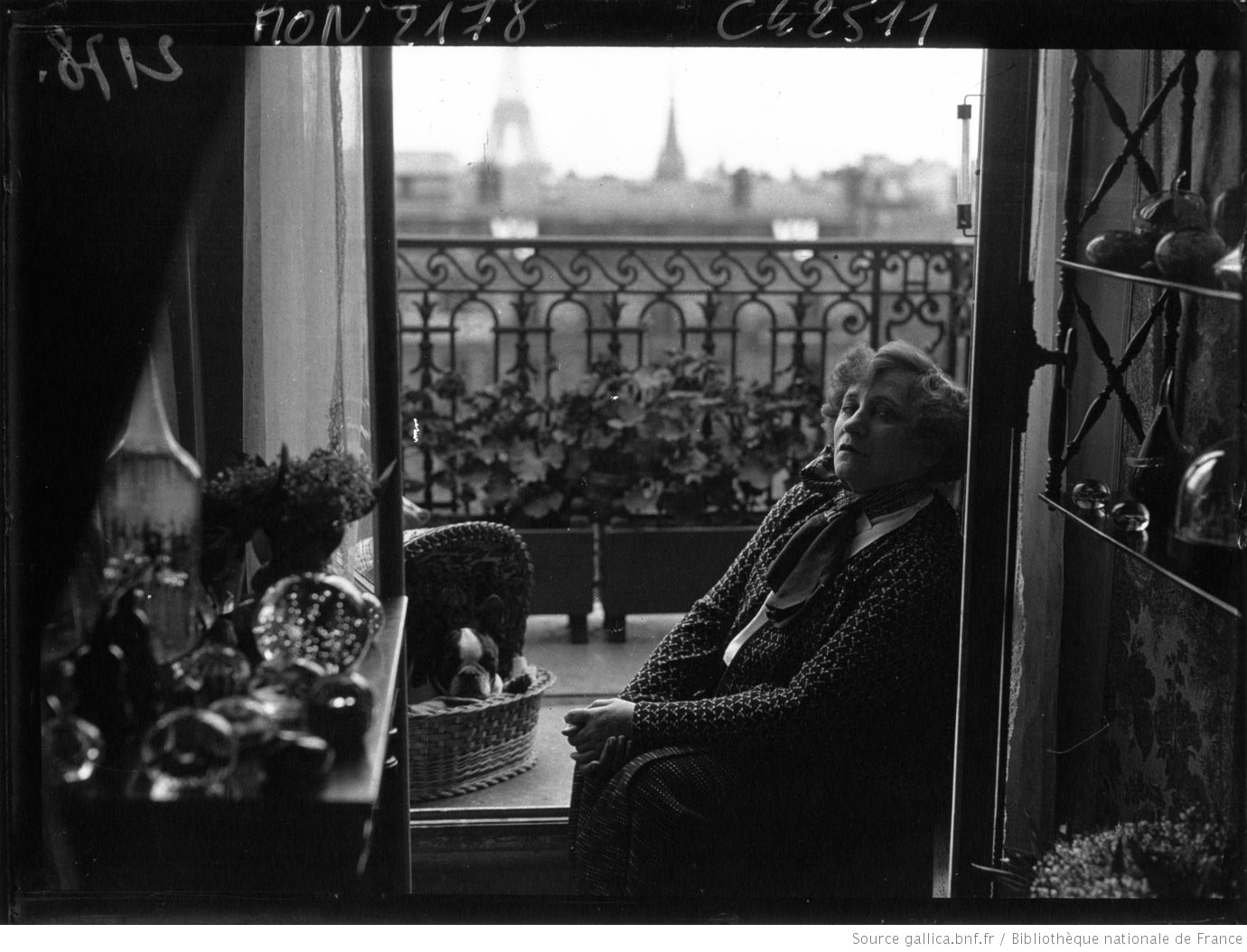

Mondial Photo-Presse

Portrait of the writer Colette, 1935

Bibliothèque nationale de France

“The only personality I would like to write about [..] is Paris, France, that is where we all were and it was natural for us to be there.” Gertrude Stein

Sadly, the collective narrative of the “Left Bank” was interrupted by World War II and the Nazi occupation of the French capital, forcing many of the women to scatter, flee or return to their home countries. From that moment on, as Andrea Weiss recounts, Paris was no longer a woman and the torch of modernity passed to New York, a cultural changing of the guard that had a great deal to do with the return of those female expatriates and the arrival of exiled European artists.

Berenice Abbott

Henry Street (Changing New York), 1935

The New York Public Library

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza