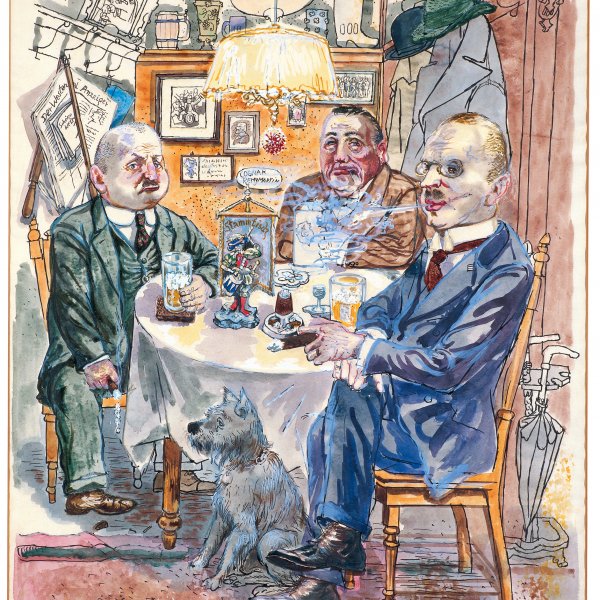

Metropolis

The transformation of the city into a vast metropolis was one of the subjects that most fascinated early twentieth-century painters, and Grosz was no exception. One of the many artists anxious to capture these rapid, constant changes, he painted this vision of Berlin at the height of the First World War in an Expressionist style in which red is the dominant colour. In it he uses Cubist and Futurist devices, a very rigid perspective and overlapping figures to convey the frenzied pace of city life. Yet whereas other painters provide a highly optimistic interpretation, Grosz—marked by his personal wartime experience—offers us an apocalyptic vision, stressing the alienation of man as he plunges headlong towards self-destruction.

Metropolis, painted by George Grosz in Berlin in the throes of the war, between December 1916 and August 1917, with an interruption due to his being called up again from January to May 1917, is a disturbing allegorical vision of a society doomed to its own destruction. The painting, a consequence of the horrors the artist had witnessed, is markedly Expressionistic in style, although the overlapping geometrical planes of the composition recall the Cubist aesthetic. Like his contemporaries Ludwig Meidner and Lyonel Feininger, in the present painting George Grosz is heavily influenced by the Futurist painters, with whose works he was familiar through the exhibitions organised by Herwarth Walden at the Der Sturm gallery in Berlin. The depiction of the hectic pace of urban life, typical of Italian Futurism, fitted in perfectly with the image of the world he wished to convey. Grosz makes the Futurist glorification of the city modern man’s fatal destiny. The dehumanised crowd we find in Metropolis is irremediably trapped in an infernal lifestyle that Grosz exaggerates by means of extremely prominent vanishing lines produced by a very rigid perspective, and above all through the predominant red of the blazing, unreal sun that illuminates the entire composition.

In his commentary on Metropolis, William Lieberman mentioned that Walter Mehring, who met Grosz in 1916, referred to this work as Reminiscences of the Entrance to Manhattan, owing perhaps to the fact that many of the preparatory drawings for the painting were imaginary renderings of New York. The German poet Theodor Daubler, in an early article about the painter, had already noted that “his conception of the big city is really apocalyptic” and stated, when describing a drawing of 1916 entitled Memory of New York, that “... the houses are geometrical, bare, like just after a bombardment. Suburban trains follow in rapid succession, like a thunderstorm they enter with a shudder at lightning speed and are away again. The people, mostly merely the expression of their greed, with pitted faces, are bewildered: one over the other!... He puts little stars in everywhere, even where there is merely writing, rhythmically linked like a stars firework. Or flying away: on the stars and stripes!” This work, like Metropolis, stemmed from the new fascination European intellectuals and artists felt for all things American as a symbol of modernity. Spurred by this admiration, in 1916, while starting work on Metropolis, the then Georg Gross decided to Americanise his name to George Grosz, which he used thereafter.

Metropolis is a significant work on account of its underlying history. In the mid-1920s it became one of Grosz’s first works to belong to a German public collection when it was acquired by the Kunsthalle of Mannheim, where the legendary Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) exhibition was staged in June 1925. The exhibition, organised by the museum’s director, Gustav Hartlaub, brought together examples of Post-Expressionist German figurative art. Shown alongside Metropolis was a work that was closely related to it, Dedication to Oscar Panizza, which, as Grosz later stated, was painted “as a protest against a mankind that had gone mad” and dedicated to this German writer who had been undeservedly confined to a psychiatric hospital and had his books banned.

With the advent of Nazism, Metropolis was exhibited in Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art), the Third Reich’s major endeavour to defame avant-garde through parody. Shortly afterwards it was among the works sold by the Nazi regime at the Galerie Fischer in Lucerne to raise money for its rearmament programme. It was bought by Curt Valentin, a German dealer who emigrated to New York, where he opened the Buchholz Gallery. Metropolis thus found its way into America, which would also become the new homeland of Grosz, who bought back this landmark work once he had stabilized his financial situation. The painting belonged to Richard L. Feigen for a time before entering the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection.

Paloma Alarcó