Circus

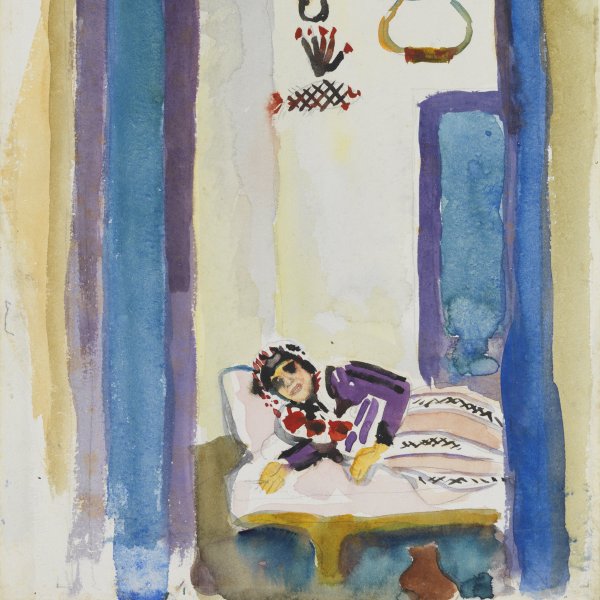

Three acrobats attend to a female rider who has had an accident. Her inert body is carried from the ring, while the horse that has caused the tragedy is led away. Closer to the foreground, a figure bending over in the shadows turns his back on the viewer in a sign of grief. In this work the circus reveals its dual nature, in which merriment can instantly transform itself into profound sadness and in which danger and death constantly lie in wait. The fragile rider and the circus can be related to August Macke, an artist who felt himself to be located on the margins of society in a way comparable to circus people.

In 1913 Macke had moved away from the Die Blaue Reiter [The Blue Rider] Expressionist group and his wanderings had taken him to Paris. His interest in Futurism, particularly the work of his close friend Robert Delaunay, is evident in this work in the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza. Macke’s focus on the expressive value of colour was combined with a fragmented concept of space derived from Delaunay in works that became the German successors to that French painter’s chromatic Cubism.

MRA

In the present painting and in Tightrope Walker, two works that are closely related, Macke rescues the theme of the circus. This performing art had previously interested many other artists on account of its colours and luminosity, and perhaps too because it was a world that went against the established norms. The factors that kindled Macke’s interest in circus subject matter during the winter of 1913–14 could be related, as Peter Vergo points out, to his move to Hilterfingen in Switzerland, on the banks of Lake Thun. There, according to a testimony of Elisabeth Macke, a family of artists called Knie used to perform in the market place. Their stunts on a wire set up in the square had impressed both her and her husband: “an unusual spectacle in richly contrasting colours such as one rarely sees. It all made a deep artistic impression on August, who translated these experiences in masterly fashion into numerous drawings and paintings.”

The scene Macke depicts in the present oil painting in the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, a riding accident in the middle of the ring, is a rather dramatic vision in which pain and death eclipse the actual performance. Painted a year before his premature death on the battle front, it is an exception in the painter’s oeuvre, which is generally characterised by its joyful and jovial nature.

The Post-Cubist language, very much consonant with Robert Delaunay’s Orphism, indicates the powerful influence this French artist exerted on Macke after they met in Paris in 1912. The canvas of the tent and the posts that support it are fragmented in a chromatic Cubism that deconstructs form through light and transforms the structure of the image into a transparent colour structure. Furthermore, the luminous colouring, a common feature of his entire oeuvre, creates a brilliant and unreal atmosphere that heightens the unsettling pathos of the scene.

Macke had already produced a first version of this theme, possibly based on a real event, in the small gouache entitled Fall dated 1911 and in a somewhat earlier charcoal drawing. Ursula Heiderich regards these compositions as a return to the traditional theme of the Pieta, evidencing the interest Macke always felt in the great masters of the past. In the manner of a dead Christ, the body of the young rider who has fallen from the horse is held by a doleful group of acrobats whose concern is expressed by their bodily poses, as Macke has deleted their facial features and expressions. According to Heiderich, the scene symbolises “the idea of danger that entails an existence on the fringes of society, like the life artists usually lead.”

Paloma Alarcó

Emotions through art

This artwork is part of a study we conducted to analyze people's emotional responses when observing 125 pieces from the museum.