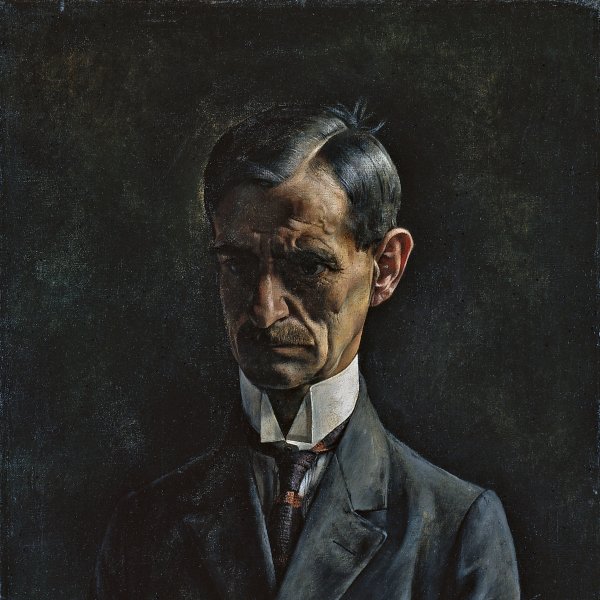

In 1955 Otto Dix recalled how, as a young artist starting his career, the painter Max Liebermann had advised him: “Above all, paint a lot of portraits! In any case, everything we Germans paint is a portrait!” Faithful to this tradition, whose origins lay in the German Renaissance, Dix executed this portrait of Hugo Erfurth with his Dog in which he not only used formal and compositional solutions derived from earlier German portraiture, such as the heavy curtain, the vivid blue background, the profile format and the presence of the dog, Ajax, but also made use of the painstaking technique of tempera on panel. This technique allowed Dix to define the smallest details in a way comparable to the German masters of the 16th century.

After a number of years in which Dix had been stylistically close to Expressionism and Dada, around 1919 his work moved towards a pronounced, harsh realism that reflected the scepticism of interwar society. This “New Objectivity” led the artist to become the acerbic portraitist of a varied group of sitters during the years of the Weimar Republic. Hugo Erfurth, a renowned society photographer and a friend of the artist, was among them.

MRA

Along with George Grosz, Otto Dix was one of the foremost practitioners of German New Objectivity. Like many of the artists who survived the war, he ceased to find the Romantic spirit of the avant-gardes appropriate and halfway through the 1920s, driven by the conviction that art could no longer change society, he progressively tempered his critical tone and revolutionary ideas. At the same time, his exaltation of human likenesses led him to devote himself to the genre of portraiture for several years. Dix produced a matchless gallery of portraits of the bourgeoisie and intellectuals of the Romanisches Café, the haunt of Berlin’s cultural bohemia. His paintings of the dancer Anita Berber, the journalist Sylvia von Harden, the abstract art dealer Alfred Flechtheim and the poet Ivar von Lücken are images that have become permanently ingrained in the collective memory as portraits of an era.

It is important to stress that for Dix, as for many of his contemporaries, this realism would be indissolubly linked to a working method heavily impregnated with references to the painting of his predecessors, as evidenced not only by certain stylistic similarities but also by the technical procedures employed. His interest in the craft aspect of painting led him to recover the techniques of the German Renaissance masters (Dürer, Cranach and Baldung Grien) described in Max Doerner’s book The Materials of the Artists and their Use in Painting (1921) — which led the witty Grosz to nickname him “Hans Baldung Dix.” From 1925 onwards, Dix nearly always painted on panel and occasionally even used mixed media, tempera and oil. The replacement of canvas by a hard board as a support enabled him to heighten the realism of his veristic style. Even the manner in which he signed his pictures evolved from the nervous, sharp handwriting of his Expressionist years to a monogram in the form of a serpent entwined around a bow and arrow — a tribute to Cranach, who signed with a small winged dragon.

Dix executed the portrait of Hugo Erfurth with Dog in 1926 on his return to Dresden from Berlin, after being appointed a professor at the Staatliche Akademie der Bildenden Künste. His friend, the photographer Hugo Erfurth, whom he had already painted the previous year holding a wide-angle lens, had been court photographer to the king of Saxony, and had later earned a certain reputation as a painter of portraits of the wealthy classes and intellectual and artistic circles of Dresden. As in most of his realist portraits, Dix adopts the traditional compositional models of portraiture: the photographer stands out against a plain background with a discreet decorative setting. Erfurth is portrayed half length dressed in his characteristic English tweed jacket and silk tie adorned with a pin set with a precious stone. He does not bear any attributes of his trade but poses with his huge dog, perhaps to symbolise the status he had attained as a photographer. Dix methodically followed the instructions given by Doerner in his book: he made two sketches on paper of the same size as the panel in which he worked out the positions of the two figures using charcoal, pencil and white chalk, and subsequently transferred the image to the panel, which he carefully painted using a tempera emulsion. Finally, he added the finishing touches with an oil glaze.

Both in this portrait, executed in 1926, and the earlier one made in 1925, as well as in the preparatory drawings for both, the painter takes particular care over the handling of the face and hands and achieves a close physical likeness and a detailed rendering of the tiniest details. Dix creates the impression of a frozen image by concentrating on objective fact, intensifying it through his hyper-realistic depiction of the details which, with its unusual precision, goes beyond appearances and lays bare the sitter’s inner character.

Paloma Alarcó

Emotions through art

This artwork is part of a study we conducted to analyze people's emotional responses when observing 125 pieces from the museum.

More details about Hugo Erfurth with Dog