The building of the Atri and Villhermosa palaces

The Atri palace

In 1746, the property on the corner of the Carrera and the Prado de San Jerónimo was acquired by Margarita Leonor Pío de Saboya, Dowager Duchess of Atri (1712−1760). A member of the Spinola family, who had settled in that part of the city back in the sixteenth century, Margarita Leonor married Domenico Acquaviva d'Aragona, 17th Duke of Atri (around 1690−1745) in 1726. After living for years in Naples, where the duke’s family was from, the couple sought a new home in Madrid in 1744. The purchase went ahead despite the duke's death the following year.

In 1748, the Dowager Duchess of Atri remarried secretly. Her second husband was Alessandro Pico della Mirandola (1705−1787). Popularly known as Abbé Pico because of his style of dress, although he had never been a priest, Pico della Mirandola enjoyed success at the court as an opera librettist and came to hold the honorary position of usher of the curtain to the king.

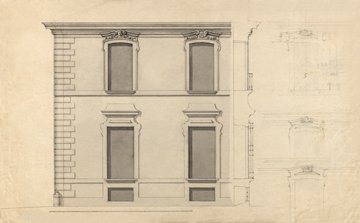

Returning to the house on the corner of the Carrera and the Prado de San Jerónimo, in 1754 the Dowager Duchess of Atri and Abbé Pico commissioned the Italian architect Vigilio Rabaglio (1711−1800) to renovate it. A collaborator of Giacomo Bonavia (1695−1759) and Giovanni Battista Sacchetti (1690−1764) and designer of the palace of Riofrío (1751), Rabaglio built a modest two-storey Rococo-style palace whose main façade, accessed via the second bay, continued to look onto the Carrera de San Jerónimo. Greater importance was given to the palace’s other façade – on the Prado de San Jerónimo – not long afterwards following the alterations undertaken by Charles III (1716−1788) to convert the Prado Viejo into a promenade, which came to be known as the Paseo del Prado.

After the death of the Dowager Duchess of Atri, the palace passed into the hands of the Abbé Pico, who sold it in 1771 to Juan Pablo de Aragón-Azlor, 11th Duke of Villahermosa (1730−1790). However, the abbé stipulated in the deed of sale that he be allowed to stay there for the rest of his life in exchange for rent. As it turned out, he did not hand over the keys until eleven years later.

The Villahermosa palace

Aragón-Azlor, a descendant of John II of Aragón and Navarra (1398−1479) and a member of one the most important Spanish noble families, had been appointed as attaché at the Spanish embassy to Paris in 1763. In the French capital he frequented the Enlightenment Salons and began assembling an important library and an extensive collection of prints. He also befriended D'Alembert (1717−1783), whose letter of introduction enabled him to visit the elderly Voltaire (1694−1778) during his retirement at the Château de Ferney, near Geneva.

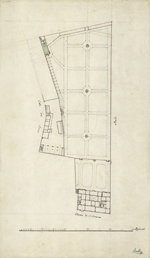

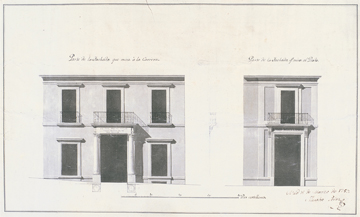

In 1769, the Duke of Villahermosa married María Manuela Pignatelli (1753−1816), daughter of the Spanish ambassador to Paris. Two years later, they acquired the Atri palace and commissioned the architect Francisco Sánchez (1737−1800), a pupil of Ventura Rodríguez (1717−1785), to draw its floor plans and elevations with a view to a future refurbishment. When the duke and duchess returned to Madrid in 1773 the palace was still occupied by the Abbé Pico and they were forced to move into another family residence near the convent of the Encarnación.

In 1778, Aragón-Azlor was appointed ambassador to Turin and it fell to María Manuela to demand the keys to the Atri palace from the Abbé Pico. He finally handed them over in 1782. Immediately afterwards, the duchess asked Juan de Villanueva (1739−1811) – who had designed the Cabinet of Natural History in Madrid, now the Museo del Prado – for an estimate of the cost of renovating the palace. The refurbishment, once again not very extensive, may have been carried out by Manuel Martín Rodríguez (1746−1823), a nephew and pupil of Ventura Rodríguez.

When Charles III died, his successor Charles IV (1748−1819) awarded the Duke of Villahermosa the Order of the Golden Fleece in 1789. Several drawings of new alterations to the palace, made by Silvestre Pérez (1767−1825), another pupil of Ventura Rodríguez, date from the same year. This time the façade – still two storeys high – was adapted to the new neoclassical taste.

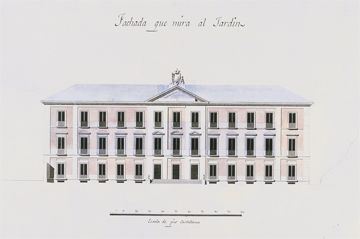

After Villahermosa's death, it was María Manuela who commissioned the final refurbishment of the palace. The first drawings were possibly made by Antonio López Aguado (1764−1831), a pupil of Villanueva and the designer of Madrid's Puerta de Toledo, among other buildings. They involved enlarging the building in area – giving it thirteen openings onto the Paseo del Prado and two inner courtyards − and also increasing its height to three storeys. However, the entrance to the palace was still located in the second bay of Carrera de San Jerónimo, while the façade overlooking the garden was restricted to nine bays – the same number as the façade on the Carrera de San Jerónimo.

After Silvestre Pérez returned from his five-year stay in Italy thanks to a travel grant in 1796, he produced a new design, locating the entrance to the palace in the centre of the façade on the Carrera de San Jerónimo. The Paseo del Prado façade now had sixteen openings and the façade overlooking the garden (owing to the uneven shape of the plot) thirteen. The design also featured three central courtyards instead of two. The last known drawings, showing two central courtyards separated by a large monumental staircase (which would eventually be replaced by an oratory), were made by López Aguado, who was responsible for the final design.

Work began in 1805 and two years later the duchess was able to move into the first bays adjacent to the Carrera de San Jerónimo. Shortly afterwards, in accordance with the ordinance prohibiting the coats of arms of two palaces – in this case those of Villahermosa and Medinaceli – from being displayed facing each other, the north façade was also completed, exhibiting the family coat of arms. Below this, on the pediment, the following inscription can still be read: ‘IN EODEM LOCO, ARTIS PERFECTIONEM ET NATURAE OBLECTAMENTUM MARIA EMMANUELA, DUCISSA DE VILLA-HERMOSA, CONSOCIAVIT’ [In this place, María Manuela, Duchess of Villahermosa, combined the perfection of art with the delight of nature].

Life in palace until the middle of the 20th century

- The palace during the Peninsular War and the reign of Ferdinand VII.

- The palace of Villahermosa houses the Artistic and Literary Lyceum.

- The Villahermosa palace during the second half of the 1800s and first half of the 1900s.