Leave-taking

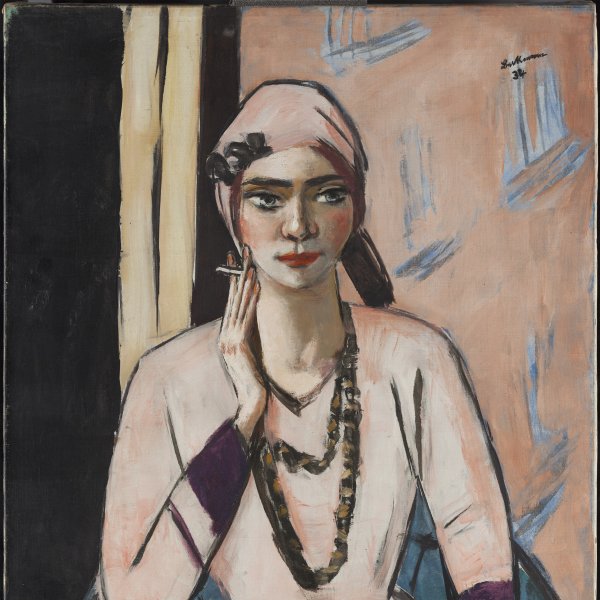

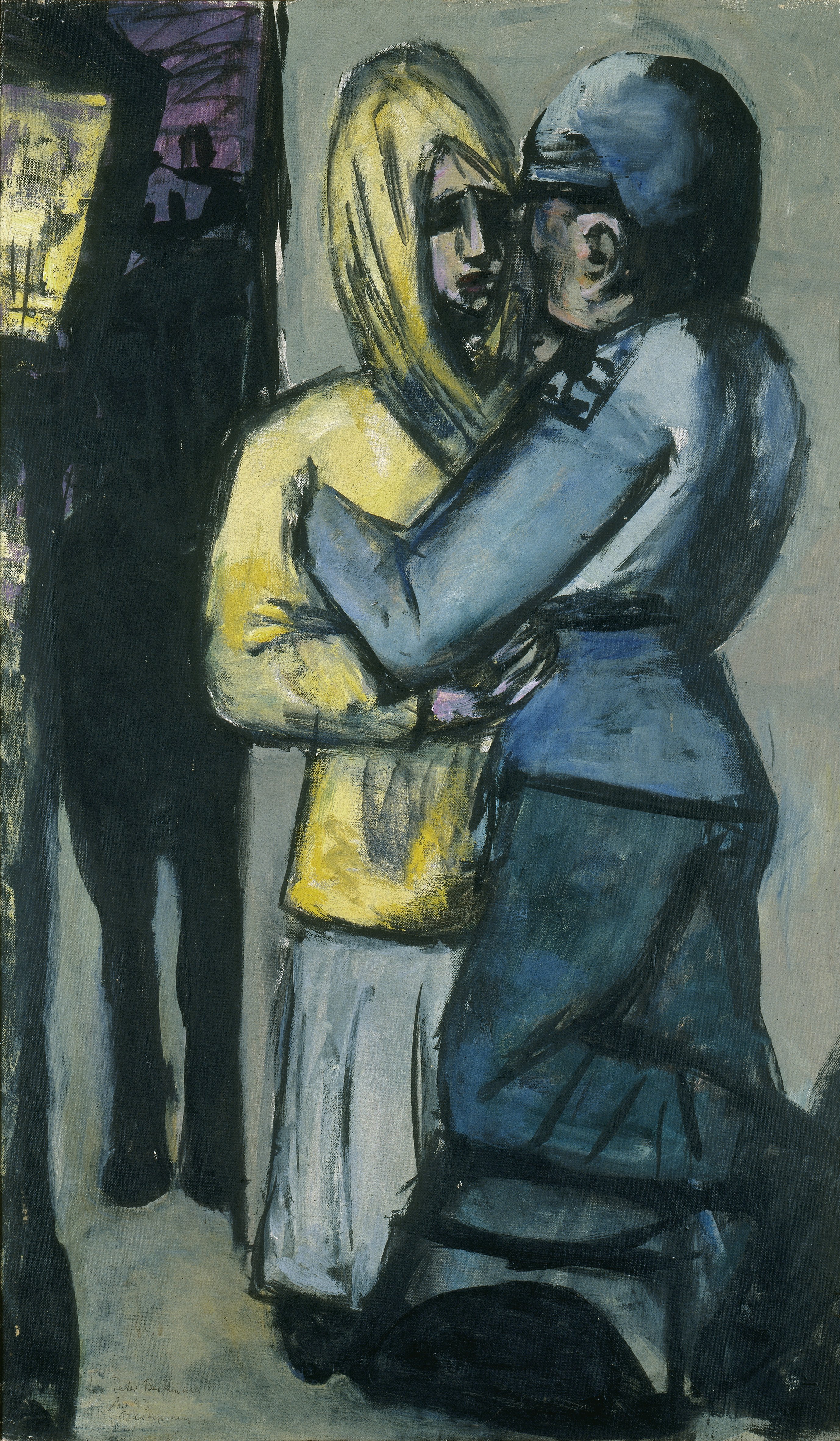

This oil was executed by Max Beckmann during his exile in Rokin, a district of Amsterdam, in the last months of 1942. It represents a couple in the foreground, the woman in the middle of the composition looking straight ahead, wearing a jacket and an acid-yellow scarf on her head, and the man in profile on the right in shades of green and blue. On the left there is a large black strip from which a kind of lamp-post protrudes, also in acid-yellow, while from the dark shadows an animal in black emerges, behind which is an area painted in violet. The man's left knee seems to be resting on a kind of stool. The two faces are looking at each other without touching, but their tones blend in together through the impastoed strokes although they are distinguishable by the yellow of the woman and the blue of the soldier's cap and jacket. His trousers tend to bluish greens, and his foot and the bench are lost in blackness. The eyes, nose and head of the beast that is gazing at this scene of leave-taking are emphasised in black against the dark mass.

According to the writer Stephan Lackner, Leave-Taking refers to the myth of Ulysses, the endless journey, the enforced exile that led Beckmann to the United States when World War II ended. In his book Ich erinnere mich gut an Max Beckmann, published in 1967, Lackner points out (p. 148) that "in his diaries he called himself 'poor Odysseus' and in his letters he referred to his own life as 'my Odyssey'". At that time, however, Beckmann was more involved in the iconography of the Apocalypse. For example, the animal in the background, which emerges from and within the blackness, refers more to the beast in the Book of St. John, as can be seen in the lithographs and even in the treatment of the black here. Beckmann was greatly influenced by Jean Paul's book Titan. This work probably combines an element of the Titan's farewell to death, symbolised by the black beast.

The "A 43" of the signature and date must be understood as Amsterdam and the date on which the painter gave the picture to his son Peter. Peter, the Beckmanns' only son, was a doctor who visited his father several times during his exile in Holland, despite having been called up because of the war. In his signatures Beckmann always put a capital letter connected with the place where he had painted the picture, whereas the date tends to correspond more to the moment when he signed or presented it than to when it was executed. Nevertheless, in the case of Leave-Taking we know the exact date when it was painted.

There are references to this picture both in the list of paintings prepared by Max Beckmann himself and in three entries in his Diaries (pp. 36-37, 373-374): "5 September 1942. Sketches finished, two 'Farewells', 'Yellow Lilies', 'Blacks' Bar' and 'Two Women'. / 20 November 1942. I worked on 'Farewell' [...]. / 15 December 1942. Indoors all day, I finished 'Farewell' almost in the dark".

The present work thus belongs to the period when Beckmann was intensely absorbed in the visual interpretation of the Apocalypse of St. John. The artist finished his 27 lithographs illustrating the Apocalypse (published in 1943 by G. Hartmann). According to his diaries, he coloured five copies by hand in April, and two more on 29 December. Leave-Taking was painted between these two dates, and in its iconography and technique there are references to the universe of the Apocalypse.

The Apocalypse was illustrated by Beckmann during his exile in Holland on a commission from Georg Hartmann (1870-1945), a Frankfurt businessman and an active patron of art. It can undoubtedly be seen as the text that offered the artist the greatest scope to reflect the spiritual and physical ruin of both Germany and Europe.

Beckmann's brushstrokes in Leave-Taking are vehement but not crude. His handling of the charcoal, his facility for sketching everything he saw, led him to construct mysterious, fascinating settings, accentuating the violence that lies beneath the calm surface of reality with great expressive force.

Here Beckmann does not add detail to the inner parts of the figures but links them together in their dialogue, their farewell, while the section on the left, the light and the animal seem to indicate the future. Rather than represent images, Beckmann constructs them. He is interested not only in the positioning of the figures but also in the way they stand out, in their shadows and in the relationship between their outlines and their shadows.

The saying that it is impossible to separate drawing and colour has always been attributed to Matisse. For that artist, drawing was the expression of the mastery of objects, and in that connection he recalled Ingres, who likened drawing to a wicker basket from which it is impossible to remove a twig without making a hole. Colour is not something added but a further form of expression. As for Edmund Husserl, colour is not something attached to objects but something consubstantial, their essence. Beckmann sought the essence of space and the essence of his painting in his handling of blackness. Blackness structured his visual thinking.

The application of colour without modelling, the distortion of the figures and the use of archetypal characters, the desire to get away from the illusion of perspective as spatial illusion, the taste for creating the painting with the same definition and intensity in all its parts, the use of black for outlining and structure, or planes of colour inscribed within a grid of lines, and the interest in printmaking techniques, are all features that establish a parallel between Beckmann's work and that of Ernst Kirchner and Georges Rouault.

In a talk given in London in 1938, Beckmann said: "My form of expression is painting, burdened or graced with a fruitful, vital sensibility, I have to seek wisdom with my eyes. I emphasise sight especially because I think that a cerebrally painted view of the world is absurd and meaningless without the frenzy given by the senses to every form of beauty and ugliness in what is visible. If this resulting form of the visible establishes literary themes which I have discovered, in other words the emergence of portraits, compositions of objects or landscapes, they arise from that condition of possibility of the senses, in this case sight, and every key theme once again becomes form, colour and space."

Kosme de Barañano