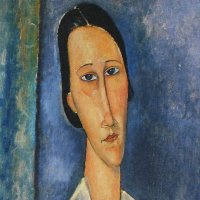

Seated Man

This canvas is one of a set of plein-air paintings produced by Cézanne in Aix-en-Provence towards the end of his life. In it, Cézanne’s gardener, Vallier, poses against the balustrade on the terrace of the artist’s new studio, close to Les Lauves. Though dressed in the plain blue work-clothes of the Provençal peasant, the sitter conveys a sense of strength and solidity, and occupies most of the picture. The vertical thrust of the figure is offset by the strong horizontal plane of the ochre-coloured parapet. By applying thinned oil paints with transparent, geometrical brushstrokes, Cézanne breaks the picture down into small planes of colour. The serene, formal arrangements of earlier years starts to disintegrate, as form and colour become inseparable in Cézanne’s quest to capture the inner structure of things.

“What I wanted was to make of Impressionism something solid and durable, like the art of museums.” With this aim in mind Cézanne, one of the participants in the first Impressionist exhibition of 1874, began to consider this pictorial language excessively ephemeral and visual and turned his attention back to classical painting. Focusing his full interest on achieving a style that combined the modern accomplishments of Impressionism and the durability of museum works, he succeeded in going much further than his Impressionist colleagues, bringing about a lasting transformation in the language of painting.

This Seated Man, whose first owner was the dealer Ambroise Vollard, belongs to a set of plein air portraits that Cézanne painted of the people of Aix-en-Provence during the latter years of his life. His gardener Vallier, who often sat for him, or some other local poses before the railing of the terrace that surrounded the facade of the building where his new studio was located, near the hill of Les Lauves north of Aix. From this terrace Cézanne painted the distant Mount Saint-Victoire, the nearby scenery and the plants in his garden, and portrayed the country folk from the neighbouring area by the huge lime tree under whose shadow he used to work. Despite the simple blue outfit characteristic of the country people of Provence, the sitter is depicted with monumental proportions and occupies much of the centre of the painting. He sits on a rustic chair with legs crossed, leaning on his stick, in a calm pose that affords him a dignity and serenity that recall the great Renaissance portraits.

This work is a good example of the style of the artist’s final years, when the still, formal arrangement of previous years began to disintegrate, the picture surface became more agitated and the colours more luminous. Endeavouring to represent the inner structure of things, Cézanne made form and colour inseparable and his compositions became more architectural. Here the verticality of the figure contrasts with the marked horizontal formed by the ochre parapet and the horizontal patches of the hat. Furthermore, the geometric, transparent brushstrokes applied with greatly diluted oils gradually shape the surface of the picture and break down the image into a continuous series of small planes of colour. The figure, which looks unfinished, is integrated into a blurred background of vegetation, perhaps a symbol of how he is perfectly in tune with the setting. As stated in John Rewald’s catalogue raisonné, Cézanne “did not follow any preconceived plan of work, so that the essential sections, such as the features of the model, could be left vague or, rather, could be attended to on a later occasion (which might never arise).” In addition, as in other works from the artist’s final period, some areas of the canvas have deliberately been left bare, forming part of the composition. Cézanne, rejecting the traditional idea of a finished work, embraced the notion of the unfinished, which went on to enjoy so much influence in all twentieth-century art.

Cézanne’s last portraits, including the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza Seated Man, were described by Lionello Venturi as “genuine dialogues with death.” Excited by their dramatic intensity, the Italian historian wrote that “Cézanne observes the old gardener with such a burden of painful compassion that it is in fact he himself who is showing himself through it, producing a sort of self-portrait so to speak. On the threshold of death, he performs his daily task: without hope, but with faith in the duty fulfilled.”

Paloma Alarcó