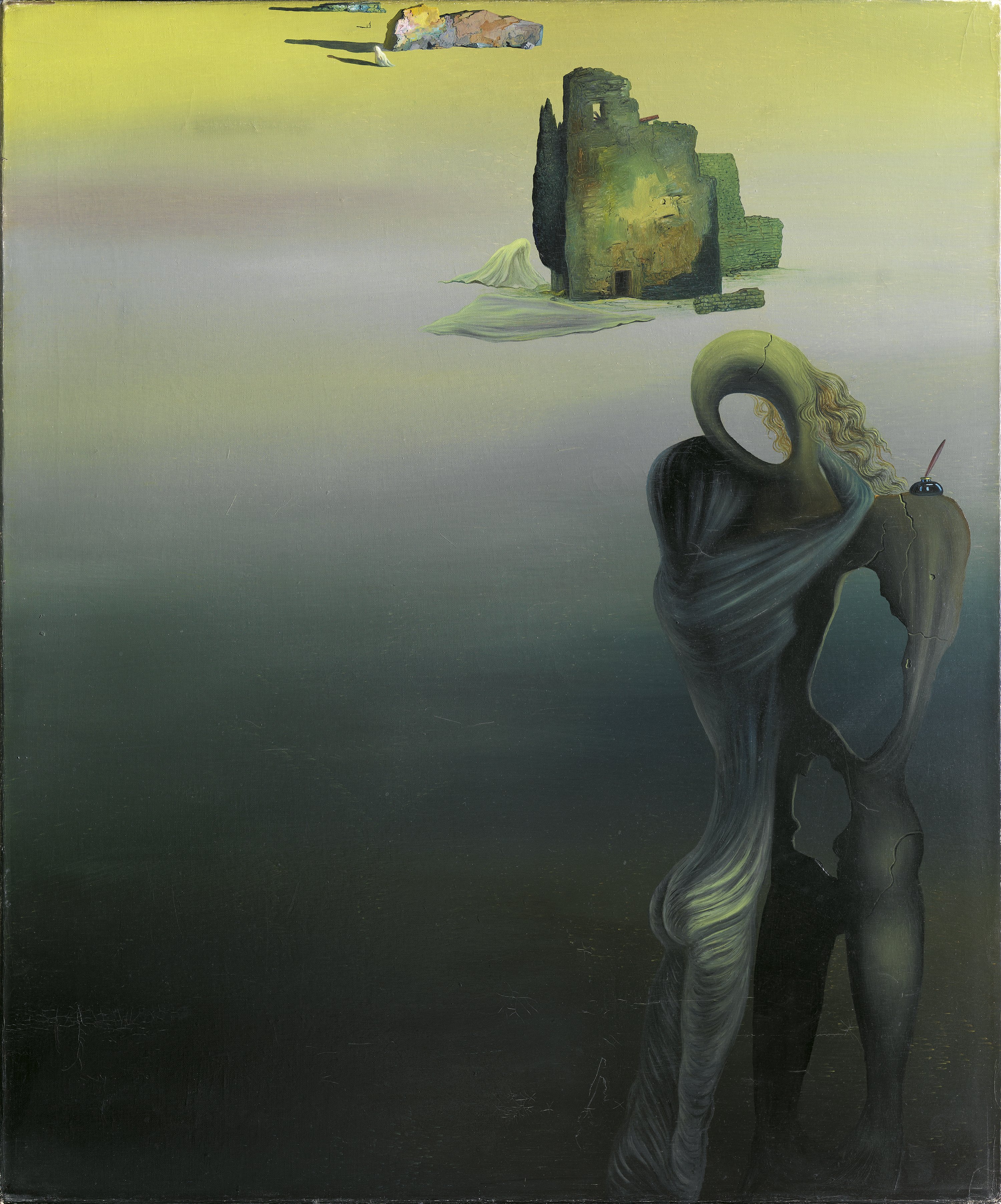

Gradiva rediscovers the Anthropomorphic Ruins (Retrospective Fantasy)

1932

Oil on canvas.

65 x 54 cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Inv. no.

511

(1975.39

)

Room 44

Level 1

Permanent Collection

When Salvador Dalí settled in Paris in 1929, he came into contact with the Surrealist group led by André Breton. That summer he invited to Cadaqués the Surrealists René Magritte, Camille Goemans, Luis Buñuel and Paul Éluard and his wife Gala, with whom Dalí immediately fell in love and who became his muse for the rest of his life. Dalí’s main contribution to Surrealism was his “paranoiac-critical method, ” developed from 1930, according to which, on the basis of Freudian theories on dream interpretation, every image could be read doubly: “The way in which it has been possible to obtain a double image is clearly paranoiac, ” the artist explains. “By a double image is meant such a representation of an object that is also, without the slightest physical or anatomical change, the representation of another entirely different object, the second representation being equally devoid of any deformity or abnormality betraying arrangement.”

Gradiva Rediscovers the Anthropomorphic Ruins (Retrospective Fantasy) is generally dated to 1931, although, as Christopher Green has pointed out, since it was not included in the major exhibition of the artist’s work at the Pierre Collé gallery in Paris the following year, it should be ascribed to 1932, after the show. Gradiva had entered Dalí’s personal mythology in 1931, the year the French translation came out of Sigmund Freud’s Delusion and Dreams in Jensen’s Gradiva, written in 1907. Freud’s essay was an interpretation of the novella by Wilhelm Jensen and was published together with a French translation of the latter. Gradiva provided Freud with an archaeological metaphor for the analysis of repressed desire and immediately aroused the interest of the Surrealists, who regarded the novella as an expression of the power of dreams and desire over reality.

The main character in Jensen’s tale is a young archaeologist, Norbert Hanold, who is obsessed by the figure of a tunic-clad woman, Gradiva, he had seen in a classical relief. The young woman appears to him in dreams when Vesuvius is about to erupt in Pompeii, and when he visits the ruins of the ancient Italian town the same phantasmagorical figure appears to him on three occasions. At first he believes her to be the incarnation of Gradiva, but he later realizes that she is his childhood love Zoe Bertgang, who immediately becomes his “Gradiva rediviva.”

The Surrealists made Gradiva their heroine and in Dalí’s case it was Gala who had the same curative effect and thus became his Gala-Gradiva. The work in the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection features two figures locked in an embrace among the ruins of the ghostly, deserted landscape; one appears to have been converted into a rock. William Jeffett interprets them as two representations of Gradiva, one the real Gradiva, the other that which is buried in the memories of the young Hanold — or, in other words, two representations of Gala-Gradiva buried in the memories of the young Dalí-Hanold.

Paloma Alarcó

Gradiva Rediscovers the Anthropomorphic Ruins (Retrospective Fantasy) is generally dated to 1931, although, as Christopher Green has pointed out, since it was not included in the major exhibition of the artist’s work at the Pierre Collé gallery in Paris the following year, it should be ascribed to 1932, after the show. Gradiva had entered Dalí’s personal mythology in 1931, the year the French translation came out of Sigmund Freud’s Delusion and Dreams in Jensen’s Gradiva, written in 1907. Freud’s essay was an interpretation of the novella by Wilhelm Jensen and was published together with a French translation of the latter. Gradiva provided Freud with an archaeological metaphor for the analysis of repressed desire and immediately aroused the interest of the Surrealists, who regarded the novella as an expression of the power of dreams and desire over reality.

The main character in Jensen’s tale is a young archaeologist, Norbert Hanold, who is obsessed by the figure of a tunic-clad woman, Gradiva, he had seen in a classical relief. The young woman appears to him in dreams when Vesuvius is about to erupt in Pompeii, and when he visits the ruins of the ancient Italian town the same phantasmagorical figure appears to him on three occasions. At first he believes her to be the incarnation of Gradiva, but he later realizes that she is his childhood love Zoe Bertgang, who immediately becomes his “Gradiva rediviva.”

The Surrealists made Gradiva their heroine and in Dalí’s case it was Gala who had the same curative effect and thus became his Gala-Gradiva. The work in the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection features two figures locked in an embrace among the ruins of the ghostly, deserted landscape; one appears to have been converted into a rock. William Jeffett interprets them as two representations of Gradiva, one the real Gradiva, the other that which is buried in the memories of the young Hanold — or, in other words, two representations of Gala-Gradiva buried in the memories of the young Dalí-Hanold.

Paloma Alarcó