Sketch for "The Yellow Christ"

s.f

Pencil on Paper.

26.7 x 18.2 cm

Carmen Thyssen Collection

Inv. no. (

CTB.2000.59

)

Room F

Level 0

Carmen Thyssen Collection and Temporary exhibition rooms

It was in Brittany, in his retreat in Pont-Aven and Le Pouldu, that Gauguin began to be interested in religious subjects, an interest which lasted until the end of his life. Clearly attracted by Catholicism, strongly felt in this province, and later, when he moved to Tahiti, by the study of the Maori religion and mythology, he abandoned conventional imagery to practice syncretism and to identify himself with the figure of the betrayed Christ of Golgotha.

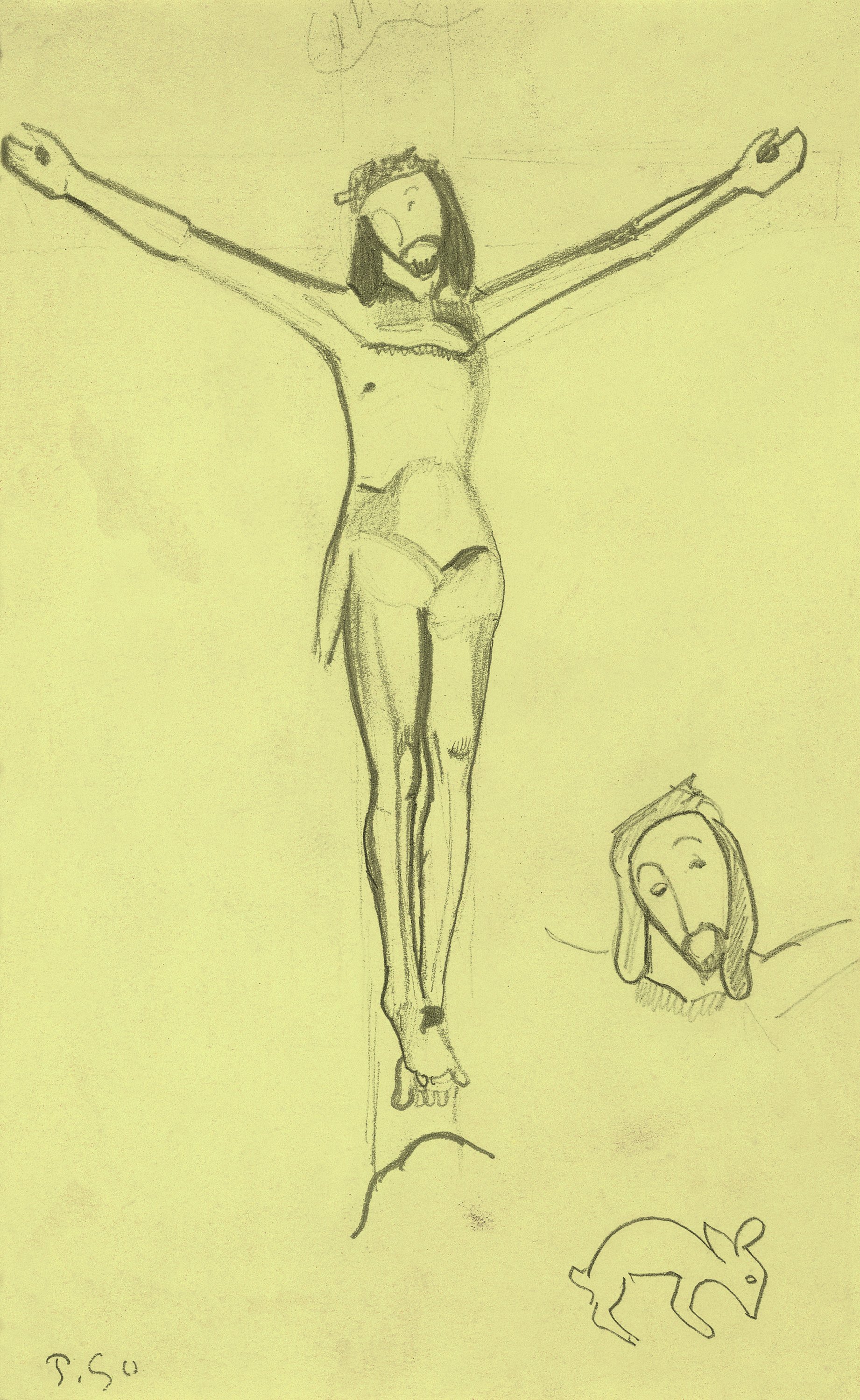

The drawing of The Yellow Christ is the first evidence of this spiritual and artistic itinerary. The chapel of Trémalo, on the heights of the Bois d'Amour, in the outskirts of Pont-Aven, hosts a 17th-century crucifix, in polychrome wood, which served as a model for this drawing. Gauguin was probably seduced by the elegance and delicacy of this suffering Christ with arms wide open, and he drew his simplified silhouette, reinforcing the outline with a marked trait. As he frequently did in his sketch books, he later took up a detail from the composition and made a portrait of Christ that was both detailed and stylised. The small animal, in the bottom right-hand corner, belongs to the sculpted decoration of grotesque figures bordering the top of the walls of the chapel.

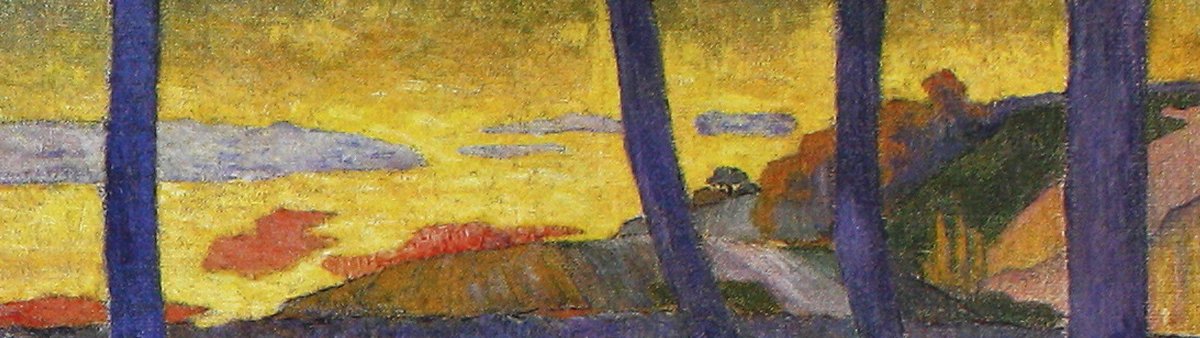

This synthetic and remarkable study of the Crucifix of the chapel of Trémalo was the starting point for Gauguin's Breton masterpiece, The Yellow Christ (Buffalo, NY, Albright-Knox Art Gallery), painted in the autumn of 1889. The Christ of the chapel of Trémalo, an image of sorrow and mystery, becomes under Gauguin's paintbrush a glowing deity and already the symbol of the new trend of his art: mystic, violent, barbaric. Octave Mirbeau was the first to feel enthusiastic towards this Calvary where "Christ, like a Papuan deity, roughly carved in a tree trunk by a local artist, the pitiful and barbaric Christ, is daubed with yellow paint." Yellow was then the artist's fetish colour.

Just before his departure for Tahiti, at a time when Gauguin was questioning himself on the meaning and the aim of his vocation, which was at the origin of so many sacrifices and so much suffering, the Christ of the chapel of Trémalo appeared again in his work. He can be seen in close-up, as a painting within a painting, behind a self-portrait and his presence gives a metaphorical meaning to the face of the artist. By associating his destiny with that of Christ, Gauguin included himself in the Wagnerian tradition which conceived art as a superior mission necessary for the salvation of mankind, and which required the artist's complete sacrifice. But the almost naive simplicity of the yellow Christ also evokes an idea cherished by Gauguin: that of redemption through the primeval and the wild.

Isabelle Cahn

The drawing of The Yellow Christ is the first evidence of this spiritual and artistic itinerary. The chapel of Trémalo, on the heights of the Bois d'Amour, in the outskirts of Pont-Aven, hosts a 17th-century crucifix, in polychrome wood, which served as a model for this drawing. Gauguin was probably seduced by the elegance and delicacy of this suffering Christ with arms wide open, and he drew his simplified silhouette, reinforcing the outline with a marked trait. As he frequently did in his sketch books, he later took up a detail from the composition and made a portrait of Christ that was both detailed and stylised. The small animal, in the bottom right-hand corner, belongs to the sculpted decoration of grotesque figures bordering the top of the walls of the chapel.

This synthetic and remarkable study of the Crucifix of the chapel of Trémalo was the starting point for Gauguin's Breton masterpiece, The Yellow Christ (Buffalo, NY, Albright-Knox Art Gallery), painted in the autumn of 1889. The Christ of the chapel of Trémalo, an image of sorrow and mystery, becomes under Gauguin's paintbrush a glowing deity and already the symbol of the new trend of his art: mystic, violent, barbaric. Octave Mirbeau was the first to feel enthusiastic towards this Calvary where "Christ, like a Papuan deity, roughly carved in a tree trunk by a local artist, the pitiful and barbaric Christ, is daubed with yellow paint." Yellow was then the artist's fetish colour.

Just before his departure for Tahiti, at a time when Gauguin was questioning himself on the meaning and the aim of his vocation, which was at the origin of so many sacrifices and so much suffering, the Christ of the chapel of Trémalo appeared again in his work. He can be seen in close-up, as a painting within a painting, behind a self-portrait and his presence gives a metaphorical meaning to the face of the artist. By associating his destiny with that of Christ, Gauguin included himself in the Wagnerian tradition which conceived art as a superior mission necessary for the salvation of mankind, and which required the artist's complete sacrifice. But the almost naive simplicity of the yellow Christ also evokes an idea cherished by Gauguin: that of redemption through the primeval and the wild.

Isabelle Cahn