William Michael Harnett

Clonakilty, 1848-New York, 1892

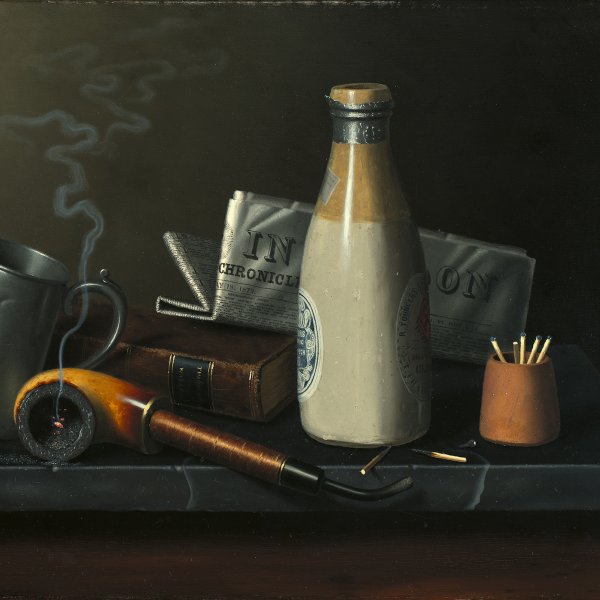

An Irishman by birth, William Harnett transformed American still-life painting of the last quarter of the nineteenth century. The use of an illusionistic technique with painstaking attention to the slightest detail, with which he created numerous trompe l’oeil effects, made him the most famous still-life painter of his day. His family emigrated to the United States not long after he was born and settled in Philadelphia, where the young Harnett started working as an engraver after his father died. In 1866 he began to attend drawing classes at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, while still working. In 1869 he moved to New York, where he continued as an engraver and furthered his art studies at the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art and the National Academy of Design. Harnett’s first still lifes date from 1874, a period in which he ceased to work as an engraver in order to open up a workshop and devote himself exclusively to painting.

In 1876 Harnett moved back to Philadelphia, where he resumed his studies and probably met John F. Peto, on whom he would exert great influence. Although his work was not highly valued by critics, by the end of the 1870s he was known to a wide audience and the proceeds from the sale of his paintings enabled him to visit Europe in 1880. During the six years he lived in the Old Continent he visited London, Munich and Paris, studied the still-life paintings of the Old Masters and introduced new themes such as hunting objects, under the influence of Adolphe Braun. Although he was very well received on returning to the United States and his works were a huge commercial success, his artistic activity became increasingly limited by a rheumatic illness from 1888 onwards and he was eventually forced to give up painting altogether in 1891. He died the following year.

In 1876 Harnett moved back to Philadelphia, where he resumed his studies and probably met John F. Peto, on whom he would exert great influence. Although his work was not highly valued by critics, by the end of the 1870s he was known to a wide audience and the proceeds from the sale of his paintings enabled him to visit Europe in 1880. During the six years he lived in the Old Continent he visited London, Munich and Paris, studied the still-life paintings of the Old Masters and introduced new themes such as hunting objects, under the influence of Adolphe Braun. Although he was very well received on returning to the United States and his works were a huge commercial success, his artistic activity became increasingly limited by a rheumatic illness from 1888 onwards and he was eventually forced to give up painting altogether in 1891. He died the following year.