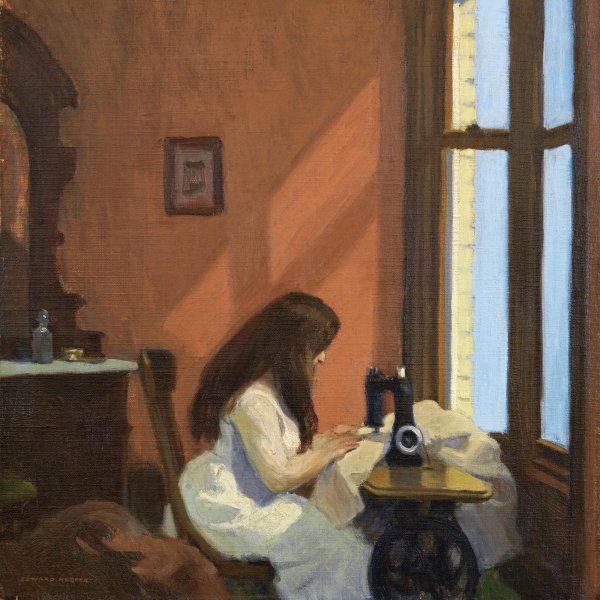

Hotel Room

The loneliness of the modern city is a central theme in Hopper’s work. In this painting, a woman sits on the edge of a bed in an anonymous hotel room. It is night and she is tired. She has taken off her hat, dress and shoes, and—too exhausted to unpack—she is checking the time of her train the next day. The space is confined by the wall in the foreground and the chest of drawers on the right; while the long diagonal line of the bed directs our gaze to the background, where an open window turns the viewer into a voyeur on what is happening in the room. The female figure, sunk in her own thoughts, contrasts with the coldness of the room, whose sharp lines and bright, flat colours are heightened by strong artificial lighting from above.

Hotel Room is an evocative metaphor of solitude, one of Hopper’s favourite subjects. It is the first in a long series of oil paintings set in different hotels, undoubtedly inspired by the artist’s fascination with travelling. It was executed a year after Sunday Morning, another tribute to the alienation of modern man, which is hailed as Hopper’s first masterpiece and was the first of his paintings to be acquired by the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Following his first taste of success, Hopper tried his hand at using a large canvas in Hotel Room. The painting shows a semi-naked young woman inside a simple room in a modest hotel on a balmy night. Josephine Nivison, Jo, the artist’s wife from 1924, wrote in her diary that she posed for this painting in the Washington Square studio and also gave a description of the composition in the artist’s notebook alongside a sketch made by him. Perhaps she has just arrived and, before unpacking, has taken off her hat, dress and shoes and sits languidly on the edge of the bed, engrossed in her own thoughts with the introspection characteristic of Hopper’s female figures. She reads a yellowed paper, which we know from Jo’s exhaustive notes to be a train timetable.

The tranquil, melancholic appearance of the figure, which is rendered on a monumental scale, contrasts with the coldness of the stark, simple, depersonalised room. The space is constructed from a few vertical and horizontal lines, which delimit large planes of unitary colour that are interrupted by the marked diagonal of the bed. It is illuminated by an artificial source that is not seen but creates a powerful contrast of light and shadow, which Hopper accentuates in order to heighten the dramatic force of the scene.

The angle from which the figure is portrayed, causing her feet to fall outside the picture plane, and the upward perspective, recall certain compositions by Degas. By using a powerful diagonal, Hopper immediately directs our gaze from the girl to the background, where a half-open window, which provides the vanishing point of the composition, reveals the pitch blackness of the night. Gail Levin, the author of the catalogue raisonné of the artist’s oeuvre, points out that this image is borrowed directly from an illustration by Jean-Louis Forain in the magazine Les Maîtres Humoristes, which Hopper had brought back from Paris. In Forain’s drawing a woman in her underclothes, seated on the edge of a bed — also positioned diagonally — stares at her lover’s shoes.

As generally occurs when contemplating the works of this American painter, the painting incites the viewer to imagine the underlying story, to guess what comes before and after the instant immortalised in his painting. On account of these narrative connotations, the work could easily be a pictorial transcription of a story narrated by Hopper’s literary contemporaries (such as Hemingway, Dos Passos, e. e. cummings or Robert Frost), who told of people’s private lives using a plain and simple language without details and incidents. Similarly, the solitude of empty interiors with open windows, alluding to feelings of frustration, was common in romantic literature, of which Hopper was particularly fond. There are also precedents in the depictions of indoor settings in seventeenth-century Dutch painting, particularly the work of Vermeer of Delft, another artist who inevitably springs to mind when we view Hopper’s paintings. The open window furthermore causes an effect of inversion, whereby Hopper brings the viewer into his work, transforming him into a voyeur.

Paloma Alarcó