In 1937, at the suggestion of Federico García Lorca, Salvador Dalí sent a letter to André Breton introducing his friend Roberto Sebastián Antonio Matta Echaurren. The painter, known simply as Matta, had been in Paris since 1933 working at Le Corbusier’s studio and sharing a house with a fellow Chilean, the writer Pablo Neruda. Breton included Matta in his Surrealist exhibition of 1938, and his first paintings were published and commented on in the magazine Minotaure. Very soon, under Breton’s intellectual patronage, the young Matta emerged as a prominent member of the Surrealist group. Shortly afterwards Marcel Duchamp persuaded him to emigrate to America, and he joined the group of Surrealist artists such as Max Ernst, Yves Tanguy and André Masson, who found refuge in New York city along with Breton during the Second World War. In 1942 Matta was included in the exhibition of artists in exile organised by the Pierre Matisse Gallery, and is portrayed in the famous photograph immortalising the event alongside Breton, Ernst, Masson, Tanguy, Eugene Berman, Marc Chagall, Fernand Léger, Jacques Lipchitz, Piet Mondrian, Amédée Ozenfant, Kurt Seligmann, Pavel Tchelitchew and Ossip Zadkine.

During his years in New York, Matta established an even greater complicity with Breton and Duchamp, with whom he shared the notion of Les Grands Transparents, invisible entities that surround human beings. Breton referred to these entities in his writings and the Chilean painter gave visual form to them in his apocalyptic settings. Matta’s emphasis on the power of violence led him to be hailed as one of the most influential figures of late Surrealism, and during the early 1940s his studio in the Greenwich district (New York) became the centre of a debate in which many of the future Abstract Expressionists took part, such as Robert Motherwell, William Baziotes, Arshile Gorky and Jackson Pollock.

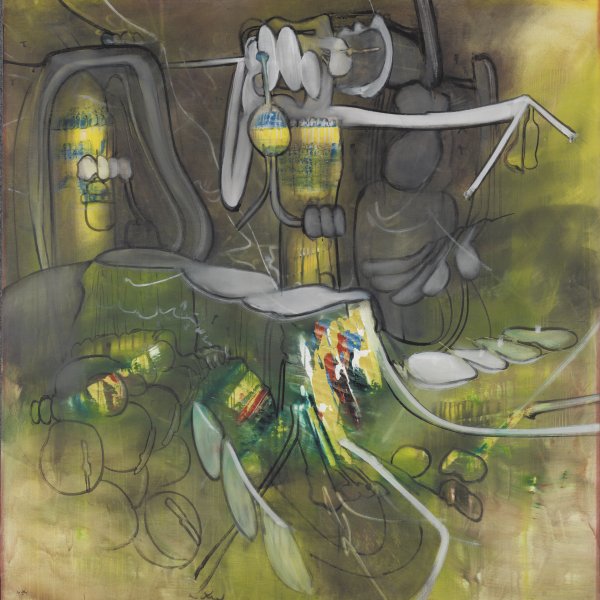

Although the titles of his paintings were essential to the Chilean painter, the present work does not have one. It has sometimes been published as Composition or Abstract Composition, but both the artist’s wife Germana Ferrari and Christopher Green prefer the more neutral name of Untitled, which is now used. Furthermore, although this small canvas belonging to the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza has been dated to around 1938‒39 on more than one occasion on account of its biomorphic forms built from fine, semitransparent layers, which greatly resemble his Psychological Morphology paintings or Inscapes (interior or mental landscapes) of the late 1930s, it is more likely to have been painted while he resided in New York.

Christopher Green convincingly proposes that the work should be dated to 1942‒43. Although related to the Psychological Morphology paintings derived from the works of Tanguy, which established a new concept of Surrealist landscape embodying uncontrolled human thoughts, Green points out that the rhomboidal incisions made in the still-wet oil, with which Matta creates a network of white linear forms that hover over the picture space, are not found in his oeuvre until October 1942. The present painting would thus be one of the first in a series executed between 1942 and 1945, referred to by Rommy Golan as the Duchampian suite, which displays linear motifs derived from the large installation produced by Duchamp for the First Papers of Surrealism exhibition staged by André Breton in New York. Duchamp’s installation, a huge Labyrinth of ropes draped across the room in all directions, disorienting the viewer, reflected the feelings of an expatriate — a status he shared with many Surrealists. Breton himself stated in “Prolégomènes à un troisième manifeste du surréalisme, ou non, ” published in New York in 1942 with illustrations by Matta, that “man must flee the ridiculous web that has been spun around him: so-called present reality with the prospect of a future reality that is hardly better.”

Paloma Alarcó

Search

Ir al contenido principal

Search

Ir al contenido principal