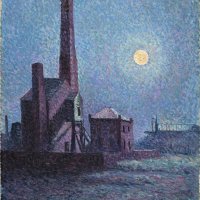

The Four Seasons: Winter

ca. 1725 - 1729

Oil on canvas.

42.5 x 33.5 cm

Carmen Thyssen Collection

Inv. no. (

CTB.1930.91

)

Room A

Level 0

Carmen Thyssen Collection and Temporary exhibition rooms

Although appreciated by his contemporaries, Pierre-Antoine Quillard was one of the French Rococo painters who quickly fell into obscurity. Only a few works can be assigned to him with certainty, and little is known about his life. According to the Abécédario pittorico by Père Orlandi (1753), he was a pupil of Watteau's. It is known that the influential Abbé de Fleury granted him a yearly allowance of 200 livres, and that he failed twice in the competition for the Prix de Rome; in 1723, he came second to Boucher, and one year later, to Carle Vanloo. In 1726, accompanying the Swiss natural scientist Charles Merveilleux, Quillard went to Portugal, where King João V made him court painter. During his few remaining years, Quillard primarily painted fêtes galantes and portraits, but also completed a few ceiling and altar decorations; in addition, he illustrated books written at the Academy of History founded by the king.

As is the case with almost all of Quillard's works, the date and provenance of the Four Seasons are not known. It is possible that they were painted before he left for Lisbon and that they originally hung in a hôtel -probably in a dining room- belonging to a cultured art lover. Like the "Four Times of Day" and the "Four Ages of Man", the "Seasons" enjoyed wide-spread popularity as a theme in contemporary writing and painting in the first half of the 18th century. In the 17th century, these paintings were usually required to contain a metaphysical, sacred symbolism that alluded to the fleeting nature of human existence, as in Poussin's work, for example. However, in their pastoral landscapes and fêtes galantes, artists such as Watteau, Lancret, Pater and Boucher celebrated rural life and the "natural" itself. In this way, they created what is undoubtedly a highly artificial contrast of the city dweller, estranged from nature and bound by social conventions.

It is not just their oval format and warm, golden-brown tones harmonised by gentle accents of colour that unite Quillard's Four Seasons, but above all the continuous compositional scheme that links them together. In Spring, Summer and Autumn, the spectator has a view of a stage-like landscape with figures dressed in the fashions of the day. Behind them are trees, behind which stretches a populated riverbank. In all of the paintings, the horizon runs along on the same level. Only Winter -a tea party set in an elegant interior- does not fit into the scheme. However, the placing and gestures of the figures, who also seem to be on a stage, correspond to the other paintings, and the mantelpiece is on the same line as the horizon in the landscapes.

The references to the various seasons can be easily deciphered: flower-picking in Spring, a cooling bath in Summer, the grape harvest and wine drinking in Autumn, and the warm fireside tea party in Winter. However, all of this classic symbolism is subordinated to one theme that binds all of the paintings: love. In Spring, city dwellers have gathered together in a garden. The stages of courting were expressed through music, but above all through the language of flowers, which was known to all classes in the 18th century. A poem accompanying an engraving of Lancret's Spring says: "What toil, to coax the tender gifts of spring to bloom! But if they will be picked by the hand of my adored, then I have not wasted my time!). The amorous entertainment is accompanied by glances, restrained gestures and movements. In the foreground, a gallant gentleman woos his still hesitant neighbour by playing the guitar. Behind him, a peasant plucks a blossom from a rose bush, while a female figure, placed diagonally in the right-hand side of the composition, gathers flowers in a basket. The centre is occupied by a couple: a lady accepts two flowers form a gardener, thereby reciprocating his declaration of love.

The social inequality of the couple is the key, not only to the image, but to the whole cycle. It symbolises a love that transcends social boundaries, that is free from formal obligations and social conventions, obeying only feelings, only sentiment. Nevertheless, there is something artificial about this yearning for natural love and the adoption of simple ways of life. This is because the gardener and the other "peasants" alike are actually costumed city inhabitants who played the "gallant villagers" in popular 18th-century masquerade games at their châteaux de plaisance or folies East of Paris. In Autumn, which is the compositional and thematic counterpart to Spring, the situation is similar. In the tradition of 17th-century Dutch genre painting, it shows a country family receiving a visit from a city dweller, wearing a jaunty hat. Here, love appears in another "natural" shape: music is also played, but the forms of communication are less refined than in Spring. Direct glances and gestures dominate; instead of seduction through flowers, we see the influence of wine. Four lines from an engraving for Lancret's Autumn praise the enjoyment of wine and love: "The nectar of autumn inflames your boldness [...] Love harvests its grapes without witnesses." In Summer, the charms of the female body in all aspects are displayed before the observer's eyes. Quillard shows the women bathing in a pure genre scene; nevertheless, for the viewer, the reference to classical mythological themes such as Diana and Acteon or Pan and Syrinx was constantly present. Quillard achieved considerable success with the bathing theme, as can be seen in the Marquis d'Arcambal's catalogue: "Tilliard [sic]. Bathing women. The scene shows a charming landscape with beautiful stretches of water. On the right side, one sees several figures bathing; one in the water, others on the bank. One of them is undressing; this subjects is graceful, painted with a light brushstroke, of a tender contrast with pretty colouring." In Winter, the city dwellers are once again in their own surroundings. In the salon, one converses, takes tea using fine gestures, and ponders the summer's amusements champêtres, to which the "dessus de porte" also alludes. Only the extinguished candle on the mantelpiece and the Grim Reaper on the rich bronze clock hint at the fleeting nature of life.

Quillard's Four Seasons are an example of the popularity of the goût de Watteau during the first third of the 18th century and clearly echo well-known works of their time. The figure showing its back in Winter appears to be borrowed from Watteau's Les Plaisirs du Bal, while the bathing figure on the right side in Summer paraphrases Watteau's Diana Leaving her Bath, and the peasant raising his glass in Autumn and the gardener in Spring quote Watteauesque flourishes. Yet, even though Quillard's contemporaries were already comparing him to Watteau, and works were still being wrongly ascribed to him as late as the early 20th century, he never attained Wateau's artistic refinement. His rather doll-like figures seem soulless, human beings and nature are not as closely related as they are in Watteau's fêtes galantes, and nature remains a stage for a historiette. Summer evinces a resemblance to the work of Pater, who painted over fifty versions of Bathers. Contrastingly, Quillard's Winter recalls the Four Seasons painted by Lancret for Leriget de La Faye.

Martin Schieder

As is the case with almost all of Quillard's works, the date and provenance of the Four Seasons are not known. It is possible that they were painted before he left for Lisbon and that they originally hung in a hôtel -probably in a dining room- belonging to a cultured art lover. Like the "Four Times of Day" and the "Four Ages of Man", the "Seasons" enjoyed wide-spread popularity as a theme in contemporary writing and painting in the first half of the 18th century. In the 17th century, these paintings were usually required to contain a metaphysical, sacred symbolism that alluded to the fleeting nature of human existence, as in Poussin's work, for example. However, in their pastoral landscapes and fêtes galantes, artists such as Watteau, Lancret, Pater and Boucher celebrated rural life and the "natural" itself. In this way, they created what is undoubtedly a highly artificial contrast of the city dweller, estranged from nature and bound by social conventions.

It is not just their oval format and warm, golden-brown tones harmonised by gentle accents of colour that unite Quillard's Four Seasons, but above all the continuous compositional scheme that links them together. In Spring, Summer and Autumn, the spectator has a view of a stage-like landscape with figures dressed in the fashions of the day. Behind them are trees, behind which stretches a populated riverbank. In all of the paintings, the horizon runs along on the same level. Only Winter -a tea party set in an elegant interior- does not fit into the scheme. However, the placing and gestures of the figures, who also seem to be on a stage, correspond to the other paintings, and the mantelpiece is on the same line as the horizon in the landscapes.

The references to the various seasons can be easily deciphered: flower-picking in Spring, a cooling bath in Summer, the grape harvest and wine drinking in Autumn, and the warm fireside tea party in Winter. However, all of this classic symbolism is subordinated to one theme that binds all of the paintings: love. In Spring, city dwellers have gathered together in a garden. The stages of courting were expressed through music, but above all through the language of flowers, which was known to all classes in the 18th century. A poem accompanying an engraving of Lancret's Spring says: "What toil, to coax the tender gifts of spring to bloom! But if they will be picked by the hand of my adored, then I have not wasted my time!). The amorous entertainment is accompanied by glances, restrained gestures and movements. In the foreground, a gallant gentleman woos his still hesitant neighbour by playing the guitar. Behind him, a peasant plucks a blossom from a rose bush, while a female figure, placed diagonally in the right-hand side of the composition, gathers flowers in a basket. The centre is occupied by a couple: a lady accepts two flowers form a gardener, thereby reciprocating his declaration of love.

The social inequality of the couple is the key, not only to the image, but to the whole cycle. It symbolises a love that transcends social boundaries, that is free from formal obligations and social conventions, obeying only feelings, only sentiment. Nevertheless, there is something artificial about this yearning for natural love and the adoption of simple ways of life. This is because the gardener and the other "peasants" alike are actually costumed city inhabitants who played the "gallant villagers" in popular 18th-century masquerade games at their châteaux de plaisance or folies East of Paris. In Autumn, which is the compositional and thematic counterpart to Spring, the situation is similar. In the tradition of 17th-century Dutch genre painting, it shows a country family receiving a visit from a city dweller, wearing a jaunty hat. Here, love appears in another "natural" shape: music is also played, but the forms of communication are less refined than in Spring. Direct glances and gestures dominate; instead of seduction through flowers, we see the influence of wine. Four lines from an engraving for Lancret's Autumn praise the enjoyment of wine and love: "The nectar of autumn inflames your boldness [...] Love harvests its grapes without witnesses." In Summer, the charms of the female body in all aspects are displayed before the observer's eyes. Quillard shows the women bathing in a pure genre scene; nevertheless, for the viewer, the reference to classical mythological themes such as Diana and Acteon or Pan and Syrinx was constantly present. Quillard achieved considerable success with the bathing theme, as can be seen in the Marquis d'Arcambal's catalogue: "Tilliard [sic]. Bathing women. The scene shows a charming landscape with beautiful stretches of water. On the right side, one sees several figures bathing; one in the water, others on the bank. One of them is undressing; this subjects is graceful, painted with a light brushstroke, of a tender contrast with pretty colouring." In Winter, the city dwellers are once again in their own surroundings. In the salon, one converses, takes tea using fine gestures, and ponders the summer's amusements champêtres, to which the "dessus de porte" also alludes. Only the extinguished candle on the mantelpiece and the Grim Reaper on the rich bronze clock hint at the fleeting nature of life.

Quillard's Four Seasons are an example of the popularity of the goût de Watteau during the first third of the 18th century and clearly echo well-known works of their time. The figure showing its back in Winter appears to be borrowed from Watteau's Les Plaisirs du Bal, while the bathing figure on the right side in Summer paraphrases Watteau's Diana Leaving her Bath, and the peasant raising his glass in Autumn and the gardener in Spring quote Watteauesque flourishes. Yet, even though Quillard's contemporaries were already comparing him to Watteau, and works were still being wrongly ascribed to him as late as the early 20th century, he never attained Wateau's artistic refinement. His rather doll-like figures seem soulless, human beings and nature are not as closely related as they are in Watteau's fêtes galantes, and nature remains a stage for a historiette. Summer evinces a resemblance to the work of Pater, who painted over fifty versions of Bathers. Contrastingly, Quillard's Winter recalls the Four Seasons painted by Lancret for Leriget de La Faye.

Martin Schieder