Pierre-Auguste Renoir

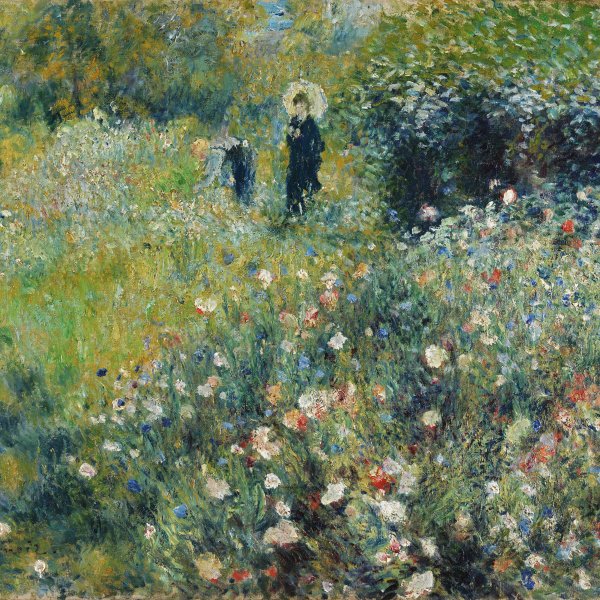

A central figure in the development of the Impressionist movement, the French artist Pierre-Auguste Renoir trained as a porcelain painter in the Lévy workshop, although his interest in painting spurred him to make regular visits to the Musée du Louvre, where he began to copy the works of the classical masters about 1860. In 1861 he attended the drawing classes taught by Charles Gleyre and was finally admitted to the École des Beaux-Arts in 1862, although he continued to frequent Gleyre’s studio, where he came into contact with Claude Monet, Alfred Sisley and Frédéric Bazille. He accompanied them on outings to the forest of Fontainebleau and was soon attracted by plein air painting.

Renoir had his first work shown at the Salon in 1864: Esmeralda, which he later destroyed. However, in the previous years the Salon rejected several of his works, which led him to exhibit at the Salon des Refusés in 1863. After an interval in which he was called up to fight in the Franco-Prussian war, Renoir showed his work in the First Impressionist Exhibition of 1874. During the years immediately after the war ended, he spent periods with Monet at Argenteuil, where the two artists created landscapes that would epitomize the Impressionist style.

Renoir ceased to take part in the Impressionist exhibitions after the third, in 1877, and from 1878 onwards his works were admitted to the official Salon. This change of attitude coincided with a creative crisis in which the artist severed his links with Impressionism. His compositions became more balanced and he attached greater importance to drawing. The influence of Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres and his trip to Italy, in which he felt especially attracted to Raphael, became evident in his new works, of which bathers were one of the most recurring themes. Seeking new sources of inspiration, Renoir travelled extensively within and outside France, visiting the museums of many European cities such as Dresden, London and Madrid. By about 1900 Renoir’s fame had spread and his reputation was established as a great artist. The turn of the century saw a worsening of his health and his rheumatic problems led him to move to a small town in the south of France, Cagnes-sur-Mer, where he bought a house that is now a museum. He was eventually forced to stop painting and took up sculpture, in which he engaged with the help of a young sculptor who followed the master’s instructions.