Lady Tz'akbu Ajaw, the ‘Red Queen’ of Palenque

Half of the World. Women in Indigenous Mexico

The government of Mexico declared 2025 as the Year of Indigenous Women, in recognition of the presence and contributions of the native peoples who have inhabited its territory and shaped the nation for more than thirty centuries. Indigenous women are a cornerstone, bedrock and backbone of the nation: the guardians of its memory, languages, traditions and ancestral knowledge, which they have preserved, resignified and adapted to modern times.

The government of Spain, through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, European Union and Cooperation and the Spanish Agency for Development Cooperation (AECID), and the government of Mexico, through the Secretariat of Foreign Affairs, the Secretariat of Culture and the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), in collaboration with the Casa de México in Spain, the Spanish Ministry of Culture, the Cervantes Institute and the Ibero-American General Secretariat (SEGIB), are presenting the exhibition entitled Half of the World: Women in Indigenous Mexico, of which this show is part. It is devoted to Lady Tz’akbu Ajaw, the ‘Red Queen’ of Palenque, an important 7th-century Maya woman who exemplifies the significance and power that came to be wielded by the women of the ruling elites, who expanded the influence of their lineages, played an active role in political and ritual life, and were the custodians of the sacred books.

Introduction

The Maya civilisation flourished more than three millennia ago in southeast Mexico as well as in Guatemala, Belize and part of Honduras and El Salvador. Its calendar and hieroglyphic writing systems, its thorough knowledge of mathematics and astronomy, its monumental architecture and its refined art attest to its greatness. But it is not merely a culture of the past: today more than thirty Maya peoples inhabit practically the same ancient territories, speak languages derived from its ancestral common predecessor, Proto-Mayan, and preserve the essence of its customs and beliefs.

Of the ancient Maya cities, Lakamha’ ‘[place of] Great Water’, now Palenque, stands out as a wonder in the jungle of Chiapas. Its architecture reveals the power of the dynasty headed by K’inich Janaab Pakal – Pakal ‘the Great’ – who enhanced the city’s artistic and political splendour in the 7th century. His wife governed alongside him: the ‘Red Queen’, Lady Tz’akbu Ajaw, whose story is a testament to the strength and legacy of Maya women.

'Red Queen'

On 13 November 672, aged between 55 and 60, Lady Tz’akbu Ajaw ‘began the journey’ after exhaling her ‘white flower’. Her body was interred in a mortuary chamber in Temple XIII-sub, accompanied by two sacrificial victims. The mukna’ burial ritual had to be performed between two and ten days after she drew her last breath. Her body and monolithic sarcophagus were covered in cinnabar (mercuric sulphide), a prized crimson pigment which had life-giving properties for the Maya.

She was buried with the objects she wore when alive to accompany her on her long journey to the underworld, as well as a mask of malachite tesserae and an elaborate headdress in the manner of a crown ornament or hu’unal (characteristic of the Maya ruling elite) which covered her face, representing the titles – linked to her bloodline and long and distinguished dynastic lineage – that she would retain for the generations to come. Her body became a relic, a link between her new post-mortem place of abode and the earth, between the living and the dead.

'Queen of the countless lineages"

Lady Tz’akbu Ajaw (or Ahpo Hel) was born in the second decade of the 7th century into the royal family of Uhx Te’ K’uh. She arrived in Palenque in 626 and married the ruler K’inich Janaab Pakal, strengthening political alliances and ensuring the dynastic continuity of the place. The couple had at least three children, two of whom were rulers: K’inich Kan Bahlam II and K’inich K’an Joy Chitam II. The third, Tiwo’hl Chan Mat, died before coming to power.

Her name means ‘Queen of the Countless Lineages’ or ‘Lady Ruler of Generations’, and she was unquestionably a powerful matriarch who complemented her husband’s role. Various monuments in Palenque display her name and titles, and the iconographic attributes in her portraits suggest that she took part in dynastic ceremonies and legitimation rituals, promoting works of architecture and art, organising banquets and supervising textile production, besides being involved in matters of politics and war in the city.

Dumbarton Oaks Panel

In this scene K’inich K’an Joy Chitam II performs a dance attired as the god Chaahk, lord of storms and sacrifices, flanked by his deceased parents: K’inich Janaab Pakal (right), with a figure of the jester god in his hands, and Lady Tz’akbu Ajaw holding a statuette of K’awiil, the god of the rulers who symbolises abundance, power and fertility.

Palace Tablet (detail)

This scene illustrates the enthronement of K’inich K’an Joy Chitam on 30 May 702. Seated on a throne in the form of a two-headed shark, he receives the icons of power from his deceased parents in the sacred realm: K’inich Janaab Pakal, on a jaguar throne, offers him the ‘drum major’ headdress, while Lady Tz’akbu Ajaw, on a serpent throne, presents him with the took’ pakal (‘knife shield’), a symbol of divine ancestral warfare.

Temple Tablet XIV

This tablet shows another posthumous scene: K’inich Kan Bahlam performs a dance in front of his mother, Lady Tz’akbu Ajaw, who, according to the inscriptions, personifies the moon goddess. She offers her son the effigy of the god K’awiil, an act that legitimises him as a ruler even after his death. The scene situates them in the primaeval sea and alludes to a mythical time, highlighting the queen’s role as an intermediary between the Palenque lineage, power, and the sacred realm.

Beginning the journey

For the ancient Maya, death was part of life. Dying marked the start of a process of gradual, lengthy separation of the spiritual forces and entities on their journey towards their place in the universe. In the case of rulers, this transition required complex preparations to prevent spiritual disintegration and culminate in a solar apotheosis, as recounted in the inscriptions about the 7th-century royal couple: K’inich Janaab Pakal and Lady Tz’akbu Ajaw. Both their bodies underwent preparations and rituals to ensure their permanence in the astral world, and they were later venerated as ancestors who continued to safeguard the wellbeing of Palenque and served as intermediaries between their descendants and the gods.

Travelling companions

Sacrificing people to accompany the deceased was a practice reserved for the burials of rulers and high-ranking figures. It was believed that, through ritual death, sacrificed individuals took on a sacred nature that facilitated communication with the divine realm and aided the deceased on their journey to the underworld. It is likely that the sacrificial victims found with Lady Tz’akbu Ajaw were part of her entourage: a nine-year-old boy who died by decapitation and a woman who may have had her heart removed.

Ritual fragance

This censer was found on the lid of the sarcophagus of Lady Tz’akbu Ajaw and was probably used during her burial ritual. It was placed over a small circular hole in the slab, possibly the psychoduct: a tube that allowed the ‘soul’ of the deceased to leave her body to begin its journey through the bowels of the earth before emerging with the stars in the east.

Censer

Palenque, Chiapas

7th century. Clay

Museo de Sitio de Palenque

Alberto Ruz L´Huillier. INAH

Attire for the underworld

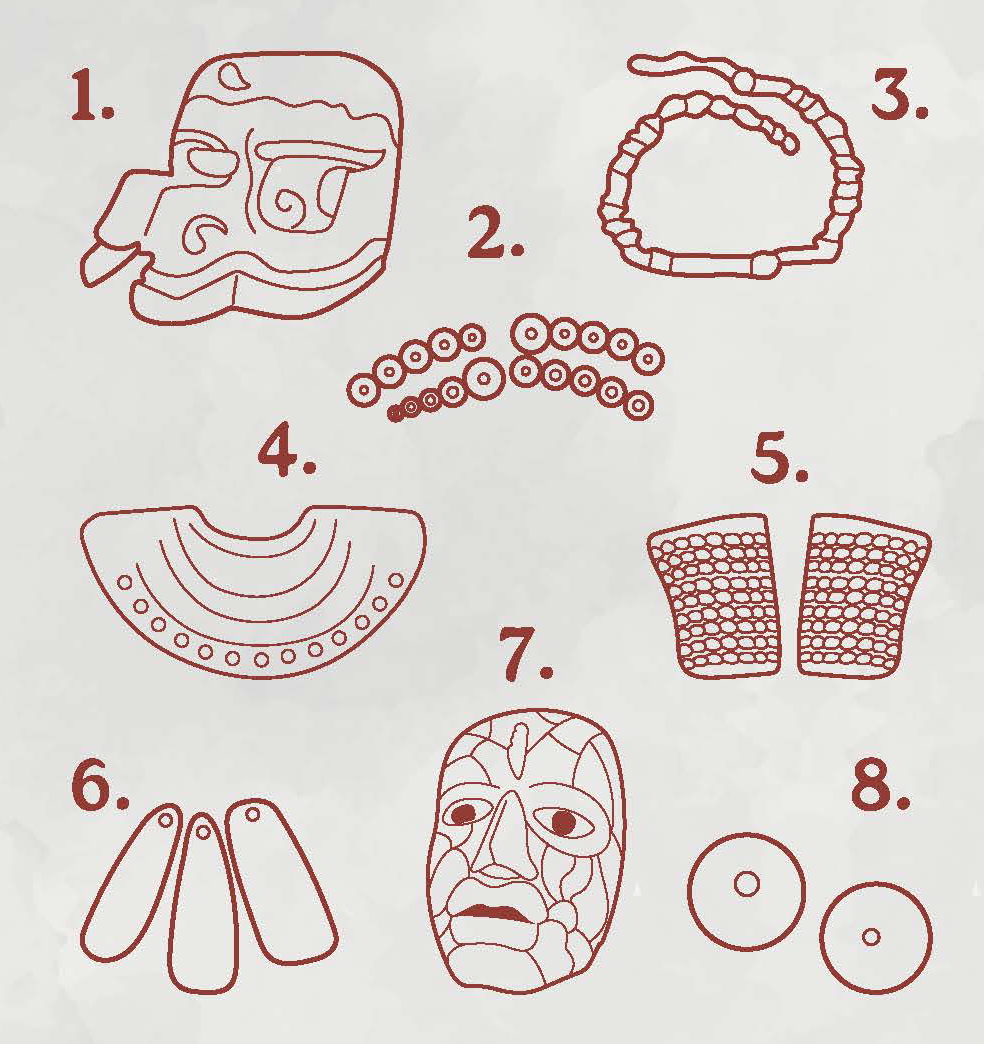

Elements of the funerary headdress of Lady Tz’akbu Ajaw evoke the characteristics of the deity GI, one of the Palenque Triad of patron gods, with celestial, solar and aquatic attributes: frontal protrusion, bulbous nose, spiral pupils, snake-like scales, shark teeth, curled fangs and feline molars. The Dumbarton Oaks panel displays a posthumous image of the ‘Queen of the Countless Lineages’ adorned with a headdress, headband, ear ornaments, pectoral and bracelets very similar to those found among her grave goods

Funerary adornments

- Headdress: jadeite, limestone and shell

- Headband: albite, quartz, jadeite and omphacite

- Necklace: jadeite and red limestone

- Pectoral: greenstone, limestone, shell and obsidian

- Bracelets: greenstone

- Belt hatchets: limestone

- Mask (possibly worn on belt): green and white jadeite, quartz and obsidian

Ankle bracelet beads: jade

Palenque, Chiapas - 7th century

Museo del Sitio de Palenque

Alberto Ruz L´Huillier. INAH

A face for the posterity

Masks made of greenstone tesserae – usually jadeite – were an important part of the grave goods of Maya rulers during the Classic period (AD 250–900), as they were thought to provide the deceased with a face for posterity. The mask of Lady Tz’akbu Ajaw was crafted from malachite, a malleable mineral that made it possible to achieve a highly realistic reproduction of her distinctive facial features, the result of her exuberance and the head shaping she underwent during infancy: a sloping skull base, prominent cheekbones, a prominent aquiline nose and an equally prominent chin.

Moon threads

Masks made of greenstone tesserae – usually jadeite – were an important part of the grave goods of Maya rulers during the Classic period (AD 250–900), as they were thought to provide the deceased with a face for posterity. The mask of Lady Tz’akbu Ajaw was crafted from malachite, a malleable mineral that made it possible to achieve a highly realistic reproduction of her distinctive facial features, the result of her exuberance and the head shaping she underwent during infancy: a sloping skull base, prominent cheekbones, a prominent aquiline nose and an equally prominent chin.

Spindle whorl and needle

Palenque, Chiapas

7th century. Animal bone and greenstone

Museo de Sitio de Palenque

Alberto Ruz L´Huillier. INAH

Sacred essence

This offering, consisting of a Spondylus shell and a limestone figurine that appears to represent the deceased queen as the corn goddess, was placed inside the sarcophagus, to the east of her head. The shell evokes the primaeval sea, and the small image could be interpreted as a receptacle for the sacred essence of Lady Tz’akbu Ajaw and a channel for ancestral communication.

Shell and figurine

Palenque, Chiapas

7th centrury. Spondylus shell and limestone

Museo de Sitio de Palenque

Alberto Ruz L´Huillier. INAH

Divine helper

This figurine was found on the floor of Lady Tz’akbu Ajaw’s crypt and is shaped like a person with achondroplasia. People with this genetic condition – often depicted in figurines and on vessels with palace scenes – were considered helpers of the corn god, which is why they also assisted rulers, both at royal courts and in the world of the dead.

Whistle-figurine

Palenque, Chiapas

7th century. Clay

Museo de Sitio de Palenque

Alberto Ruz L´Huillier. INAH

Provisions for the journey

These vessels were found on the steps leading to Lady Tz’akbu Ajaw’s crypt and probably contained food and beverages such as tamales, atole and chocolate so that the deceased would not lack sustenance during her perilous journey to the underworld. It was believed that on arriving there, her ‘soul’ would occupy an eternal place, although she could return and take part in the rites of her descendants, as shown on the tablets depicting the ‘Red Queen’ as a living presence.

Beakers and plate

Palenque, Chiapas

7th century. Clay

Museo de Sitio de Palenque

Alberto Ruz L´Huillier. INAH