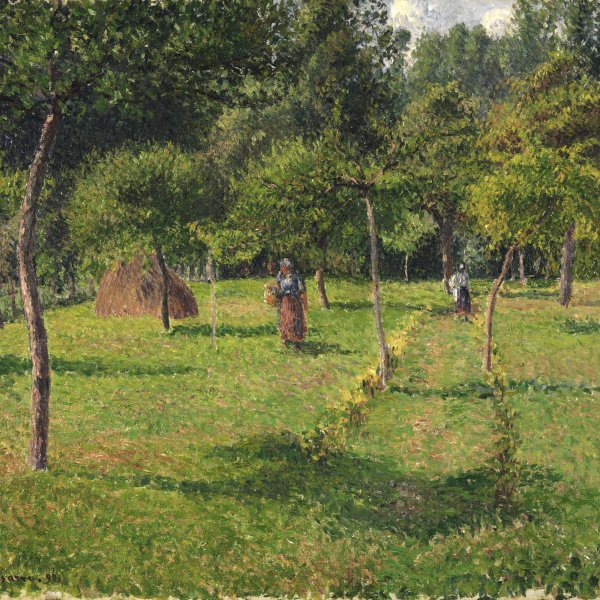

Women Sewing

ca. 1898

Oil on Cardboard.

69 x 61.5 cm

Carmen Thyssen Collection

Inv. no. (

CTB.2000.64

)

Room F

Level 0

Carmen Thyssen Collection and Temporary exhibition rooms

Marius Mermillon, who was his first biographer, said that Albert André was unclassifiable; however, he is linked to «that intermediate generation between the Impressionists and the determined revolutionaries of post 1900» (R. Chanet) which gathered both the divisionists and the members of the Pont-Aven school which Roger Fry described as post-Impressionists.

Although he never joined any group, the young Albert André undoubtedly shared with Valtat and d´Espagnat the tastes of his friends Vuillard and Roussel (Nabis group). According to Maurice Denis, he too considered that a painting was, above all, «a flat surface covered with colours put together in a particular way, » he too admired Degas and his compositions which totally changed tradition, and he too adopted a high perspective. Then, after having practised a decorative type of painting (the titles of his works testify to it: Woman in Blue, 1894; Woman with Peacocks, 1895), he turned to indoor scenes where the artificial light of a lamp reveals the charm of everyday middle-class objects, and the protagonists, with simplified outlines, read, day-dream, chat or drowse.

Women Sewing is the open air version of the indoor scenes of families gathered under the lamplight. The painting is composed like an indoor scene, but the sunlight replaces the lamplight. It is a warm light, that of the south of France, of the village of Laudun (Gard) where the artist had spent his holidays since his childhood.

When Albert André painted Women Sewing, he had already been noticed by Thadée Nathanson, the founder of the Revue Blanche, who wrote about him: «His compositions show a pleasant style and an easy boldness.» Skillfully composed, joyously coloured, these works are those of a painter smitten with light and modern life who takes his subjects from everyday life. He is the painter of simple happiness.

In the foreground three women sew in the shade of eucalyptus or plane trees. There, everything is roundness: roundness of the skirts, roundness of the movements, of a back, of a hat, and of a garden table, which contrasts with the three rigidly vertical lines of the trees.

The faces and the movements are concentrated on the work. They are not portraits. Each face is barely suggested by a simple point which marks the eye. Who these women are is not important, they are part of the house, of the landscape, and contribute to the harmony of the painting, to its colourful and bright composition. The eye, attracted by the whiteness of the work which contrasts with the red dress, then moves to the path lined with white-flowered shrubs which leads it to the dazzling bright wall of the house. The red of the dress is echoed by that of the geraniums and the tiles of the roof. The brushstroke is supple but constructive.

Everything here shows us Albert André's concern for composition and for the science of colour agreements. He did not copy anyone; he was at the same time himself and the representative of his own period, which any artist, however individualistic or original he may be, necessarily reflects. His style evolved throughout the years, but he remained deeply attached to his village, Laudun, and to the representation of garden scenes, where, in the shade of the tall trees, the women pick flowers, chat, darn, or rest...

Albert André was not a revolutionary, his art did not provoke passions, it addressed simple feelings. It still perpetuates an art made of harmony.

Evelyne Yeatman-Eiffel

Although he never joined any group, the young Albert André undoubtedly shared with Valtat and d´Espagnat the tastes of his friends Vuillard and Roussel (Nabis group). According to Maurice Denis, he too considered that a painting was, above all, «a flat surface covered with colours put together in a particular way, » he too admired Degas and his compositions which totally changed tradition, and he too adopted a high perspective. Then, after having practised a decorative type of painting (the titles of his works testify to it: Woman in Blue, 1894; Woman with Peacocks, 1895), he turned to indoor scenes where the artificial light of a lamp reveals the charm of everyday middle-class objects, and the protagonists, with simplified outlines, read, day-dream, chat or drowse.

Women Sewing is the open air version of the indoor scenes of families gathered under the lamplight. The painting is composed like an indoor scene, but the sunlight replaces the lamplight. It is a warm light, that of the south of France, of the village of Laudun (Gard) where the artist had spent his holidays since his childhood.

When Albert André painted Women Sewing, he had already been noticed by Thadée Nathanson, the founder of the Revue Blanche, who wrote about him: «His compositions show a pleasant style and an easy boldness.» Skillfully composed, joyously coloured, these works are those of a painter smitten with light and modern life who takes his subjects from everyday life. He is the painter of simple happiness.

In the foreground three women sew in the shade of eucalyptus or plane trees. There, everything is roundness: roundness of the skirts, roundness of the movements, of a back, of a hat, and of a garden table, which contrasts with the three rigidly vertical lines of the trees.

The faces and the movements are concentrated on the work. They are not portraits. Each face is barely suggested by a simple point which marks the eye. Who these women are is not important, they are part of the house, of the landscape, and contribute to the harmony of the painting, to its colourful and bright composition. The eye, attracted by the whiteness of the work which contrasts with the red dress, then moves to the path lined with white-flowered shrubs which leads it to the dazzling bright wall of the house. The red of the dress is echoed by that of the geraniums and the tiles of the roof. The brushstroke is supple but constructive.

Everything here shows us Albert André's concern for composition and for the science of colour agreements. He did not copy anyone; he was at the same time himself and the representative of his own period, which any artist, however individualistic or original he may be, necessarily reflects. His style evolved throughout the years, but he remained deeply attached to his village, Laudun, and to the representation of garden scenes, where, in the shade of the tall trees, the women pick flowers, chat, darn, or rest...

Albert André was not a revolutionary, his art did not provoke passions, it addressed simple feelings. It still perpetuates an art made of harmony.

Evelyne Yeatman-Eiffel