Sunlight

1923

Oil on canvas.

63.2 x 62.2 cm

Carmen Thyssen Collection

Inv. no. (

CTB.1999.33

)

Room F

Level 0

Carmen Thyssen Collection and Temporary exhibition rooms

Although his assimilation of the lessons of Gauguin and his emphasis on decorative composition distinguished him from the Impressionists, over time Bonnard returned to them; in a sense he was the last great heir of Impressionism until well into the 20th century. The radical tendency of Matisse and the Fauves, firstly, and later Cubism distanced Bonnard from avant-garde trends and his painting became more atmospheric and naturalistic. There was an accentuation of his affinities with Monet and especially Renoir, with whom he shared an interest in the nude and a tendency to dissolve the edges of shapes with fluffy brushstrokes. From the time of the Great War onwards, Bonnard became a kind of antidote to the accelerated experimentation of the avant-gardes for art lovers and more moderate critics.

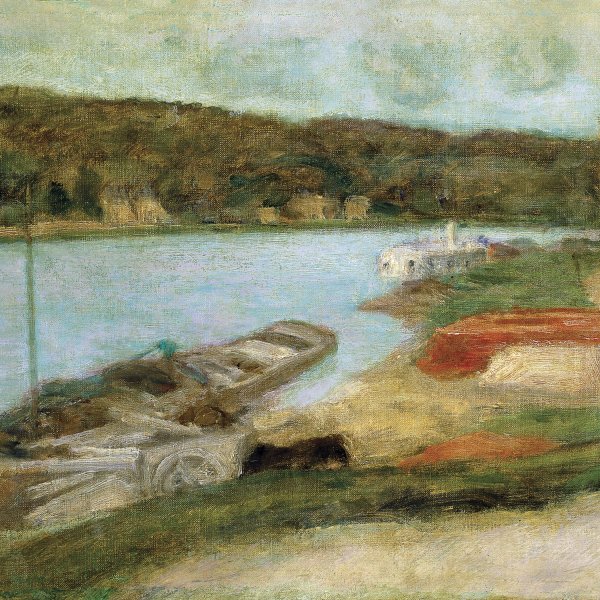

Bonnard's constant focus on landscape became more pronounced in the 1920s. A good many of his works were painted in Normandy in the house that the artist owned near Vernon, on the banks of the Seine. Even when he moved to Le Cannet, near Cannes, he continued to visit Normandy every year, as he loved its light so much. In contrast to the Impressionists, Bonnard did not paint his landscapes directly from the subject but rather worked from memory with the aid of drawings. He was happy to start a canvas in Normandy and finish it in the Midi, blending his impressions of north and south.

The present landscape shows a view of the garden of "Ma Roulotte", the artist's house in Normandy, a garden that grew wild in a woodland profusion. In the foreground there is a winding path with a cat, humorously indicating the scale of the tall trees. In the background, glimpsed through the foliage, is the river, a tributary of the Seine which the artist used to explore in his boat.

Picasso, who loathed Bonnard's style of painting, left us a description of it that is in fact revealing if we discount its critical tone. Bonnard, he said, "never goes beyond his sensibility. He does not know how to select. When he paints a sky, for example, first of all he paints it blue, more or less the way it is. Then he looks at it a little more closely and sees some mauve; so he adds a touch or two of mauve, without committing himself. And then he says to himself that there is also a bit of pink. So there is no reason not to add pink too. The result is a hotchpotch of indecision. If he goes on looking for long, he ends up by adding yellow, instead of deciding what colour the sky should really be. It's impossible to work like that. Painting is not a matter of sensibility. One must seize control, taking the place of nature and not being dependent on the information that nature provides." Picasso also referred to Bonnard's tendency to "fill the whole surface of the canvas, creating a continuous extension that quivers imperceptibly, from brushstroke to brushstroke, from centimetre to centimetre, but is completely devoid of contrast. Black is never set against white, nor a circle against a square, nor a sharp angle against a curve. In this highly orchestrated surface which develops organically, you search in vain for an unexpected cymbal clash striking with calculated violence".

The indecision that Picasso criticised in Bonnard was simply an extreme form of loyalty to sensation, with its whole range of delicate, shifting nuances. From such impalpable, inconstant material Bonnard created a continuous, seamless tapestry. In this picture, where the essential theme is the luxuriance of the vegetation, the texture of leaves and branches is suggested by the subtle texture of merged, overlapping brushstrokes. Diffuse touches of white and yellow indicate the glints of the dazzling sunlight and add a magical quality to the entire scene.

Guillermo Solana

Bonnard's constant focus on landscape became more pronounced in the 1920s. A good many of his works were painted in Normandy in the house that the artist owned near Vernon, on the banks of the Seine. Even when he moved to Le Cannet, near Cannes, he continued to visit Normandy every year, as he loved its light so much. In contrast to the Impressionists, Bonnard did not paint his landscapes directly from the subject but rather worked from memory with the aid of drawings. He was happy to start a canvas in Normandy and finish it in the Midi, blending his impressions of north and south.

The present landscape shows a view of the garden of "Ma Roulotte", the artist's house in Normandy, a garden that grew wild in a woodland profusion. In the foreground there is a winding path with a cat, humorously indicating the scale of the tall trees. In the background, glimpsed through the foliage, is the river, a tributary of the Seine which the artist used to explore in his boat.

Picasso, who loathed Bonnard's style of painting, left us a description of it that is in fact revealing if we discount its critical tone. Bonnard, he said, "never goes beyond his sensibility. He does not know how to select. When he paints a sky, for example, first of all he paints it blue, more or less the way it is. Then he looks at it a little more closely and sees some mauve; so he adds a touch or two of mauve, without committing himself. And then he says to himself that there is also a bit of pink. So there is no reason not to add pink too. The result is a hotchpotch of indecision. If he goes on looking for long, he ends up by adding yellow, instead of deciding what colour the sky should really be. It's impossible to work like that. Painting is not a matter of sensibility. One must seize control, taking the place of nature and not being dependent on the information that nature provides." Picasso also referred to Bonnard's tendency to "fill the whole surface of the canvas, creating a continuous extension that quivers imperceptibly, from brushstroke to brushstroke, from centimetre to centimetre, but is completely devoid of contrast. Black is never set against white, nor a circle against a square, nor a sharp angle against a curve. In this highly orchestrated surface which develops organically, you search in vain for an unexpected cymbal clash striking with calculated violence".

The indecision that Picasso criticised in Bonnard was simply an extreme form of loyalty to sensation, with its whole range of delicate, shifting nuances. From such impalpable, inconstant material Bonnard created a continuous, seamless tapestry. In this picture, where the essential theme is the luxuriance of the vegetation, the texture of leaves and branches is suggested by the subtle texture of merged, overlapping brushstrokes. Diffuse touches of white and yellow indicate the glints of the dazzling sunlight and add a magical quality to the entire scene.

Guillermo Solana