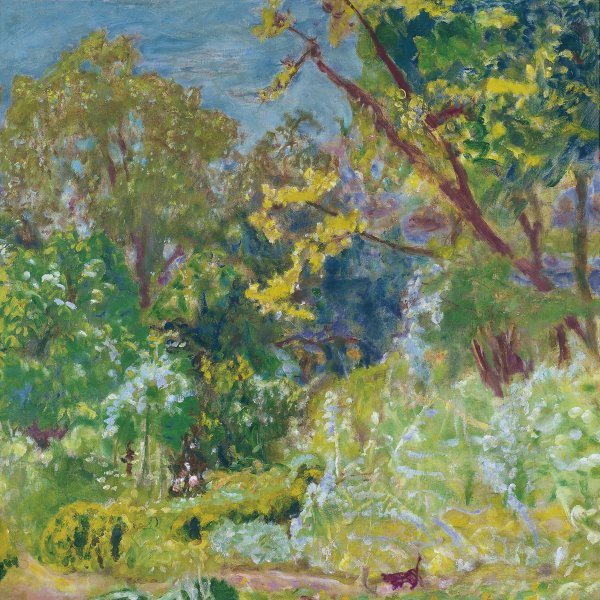

The dipping Path

ca. 1922

Oil over pencil on canvas.

46.3 x 55.3 cm

Carmen Thyssen Collection

Inv. no. (

CTB.2000.3

)

Room F

Level 0

Carmen Thyssen Collection and Temporary exhibition rooms

Although in the first decade of his career Bonnard was primarily a Parisian painter, from 1900 onward he began to move away from the capital. For some time he kept an interest in urban subjects, but towards 1912 landscape painting had become one of his main passions (although not the only one, if we recall his growing dedication to the nude). The artist's interest in landscapes lasted throughout the decade of the 1920s. In contrast with the Impressionists, Bonnard usually created his landscapes from memory. He would start from a small, quick pencil drawing, executed in ten or fifteen minutes, in the field. Afterwards, (sometimes immediately, other times years later), he would choose the size of the work and begin painting.

In 1922, the period when The Dipping Path was executed, Bonnard painted around twenty-two landscapes of Normandy and of the Côte d'Azur; the north and south of France were the two poles competing for his attention. Charles Terrasse, the artist's nephew, told Brassaï that Bonnard found the light of the north more interesting than that of the south: "Undoubtedly, my uncle believed that nowhere was the sky so beautiful and changeable as in Deauville, Trouville, Honfleur. And he also loved the trees which are found in the north: the ash trees, the lindens, the chestnuts, the apple trees." In 1933, Bonnard confessed to an acquaintance, professor Hahnloser: "I cannot paint in the South. There are no colours, there." If in his southern landscapes, executed in a decorative style and a monumental scale, Bonnard often resorted to mythological allusions; his northern landscapes have a more realistic character and are based exclusively on everyday themes and anecdotes. Such is the case of the landscape we are dealing with, the view of a path near the artist's house in Vernon, on the banks of the Seine. In Bonnard's landscapes there are usually hidden presences, which take some time to discover. Here, it is the picturesque and humoristic motif of the hens crossing the path (we find something similar in Gauguin's Tropical Vegetation, Martinique, of 1887).

In his organisation of the visual field, Bonnard cultivated at the same time two landscape models: an open one, and a closed one. On one hand, we have the landscapes representing a panoramic view, spanning the whole length of the horizon; on the other, the works where the fields or the sea are framed by a window, a balcony or a door (a similar strategy to the use of mirrors for framing figures and objects indoors). In this case, without resorting to such techniques, the path is cut deep into the earth, between the bushes, and framed on the left by the wall of a house surrounded by a fence. Whereas in the panoramic landscapes the fields are seen from a raised point of view, here the opposite takes place: the eye is situated below the horizon, and the dipping ground prevents the beholder from viewing the landscape with a single glance, which provokes a certain sense of enclosure.

Guillermo Solana

In 1922, the period when The Dipping Path was executed, Bonnard painted around twenty-two landscapes of Normandy and of the Côte d'Azur; the north and south of France were the two poles competing for his attention. Charles Terrasse, the artist's nephew, told Brassaï that Bonnard found the light of the north more interesting than that of the south: "Undoubtedly, my uncle believed that nowhere was the sky so beautiful and changeable as in Deauville, Trouville, Honfleur. And he also loved the trees which are found in the north: the ash trees, the lindens, the chestnuts, the apple trees." In 1933, Bonnard confessed to an acquaintance, professor Hahnloser: "I cannot paint in the South. There are no colours, there." If in his southern landscapes, executed in a decorative style and a monumental scale, Bonnard often resorted to mythological allusions; his northern landscapes have a more realistic character and are based exclusively on everyday themes and anecdotes. Such is the case of the landscape we are dealing with, the view of a path near the artist's house in Vernon, on the banks of the Seine. In Bonnard's landscapes there are usually hidden presences, which take some time to discover. Here, it is the picturesque and humoristic motif of the hens crossing the path (we find something similar in Gauguin's Tropical Vegetation, Martinique, of 1887).

In his organisation of the visual field, Bonnard cultivated at the same time two landscape models: an open one, and a closed one. On one hand, we have the landscapes representing a panoramic view, spanning the whole length of the horizon; on the other, the works where the fields or the sea are framed by a window, a balcony or a door (a similar strategy to the use of mirrors for framing figures and objects indoors). In this case, without resorting to such techniques, the path is cut deep into the earth, between the bushes, and framed on the left by the wall of a house surrounded by a fence. Whereas in the panoramic landscapes the fields are seen from a raised point of view, here the opposite takes place: the eye is situated below the horizon, and the dipping ground prevents the beholder from viewing the landscape with a single glance, which provokes a certain sense of enclosure.

Guillermo Solana