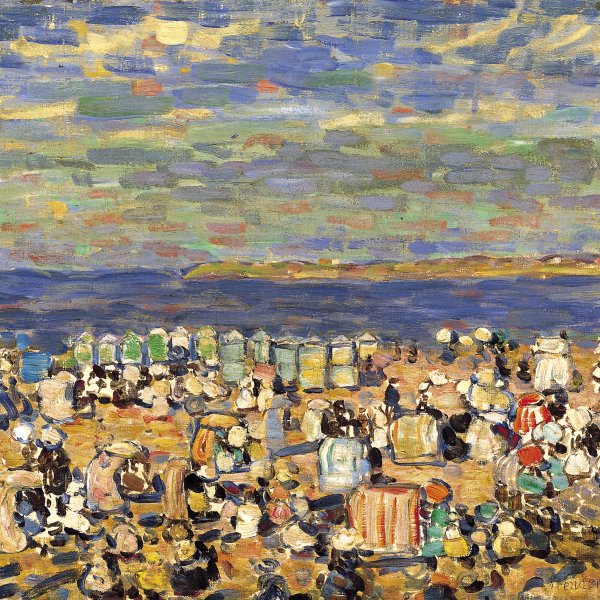

The Picnic

1907

Oil on canvas.

72.5 x 65.3 cm

Carmen Thyssen Collection

Inv. no. (

CTB.1997.21

)

Room E

Level 0

Carmen Thyssen Collection and Temporary exhibition rooms

The theme of the picnic was popular in American Art extending from Thomas Cole's The Pic-Nic, 1846 (New York, The Brooklyn Museum of Art) to Florine Stettheimer's Picnic at Bedford Hills, 1918 (Philadelphia, PA, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts). For the 19th-century American, the picnic offered a social milieu less bounded by the structures of Victorian morality; for the 20th-century American, it combined the amenities of urban life, as often evident in the carefully provided provisions of lavishly prepared food, with the healthfulness and well-being associated with the countryside.

The Picnic, with its number of leisurely celebrants, is somewhat unusual for Metcalf, who has been characterised as depicting "the pure landscape with only now and then the rarest and faintest suggestion of the figure." With its screen of attenuated trees in the foreground through which the distant landscape is glimpsed, the painting resembles both The Golden Screen, 1906 (Washington, DC, Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution) and Dogwood Blossoms, 1906 (Private Collection). While his paintings in 1905-1906 were found to exhibit a "particular joyousness, " which was "expressed vigorously in the flowers that bloom in profusion, " The Picnic, with its touch of autumnal colouring, hints at a sense of melancholy. The picnic, a communal activity filled with social camaraderie, is instead portrayed with figures that seem isolated and estranged from each other. The quadrant of sunlit clearing is empty, the picnickers are pushed to the edges. The central figure stares vacantly towards the viewer. As Catherine Beach Ely has asked: "Is the wistful quality faintly tinged with sadness which seems to emanate from his pictures inherent in the artist or in the scene he portrays?"

Metcalf's canvas was painted shortly after a traumatic period in the artist's life. In 1906 he had realised his first substantial economic success as a painter. But while at the Old Lyme art colony the following year, he became anti-social, withdrawing into his room, as he realised that his wife was becoming increasingly involved with his former student, Robert Nisbet. They ran away together in July, causing a great scandal which forced Metcalf to leave Old Lyme. Metcalf, embarrassed by the incident, left the artists' colony, travelling through New England for the rest of the summer. He returned to Old Lyme in September, and it was probably then that he painted The Picnic.

Metcalf has been considered the single American Impressionist who captured the essence of the American landscape. This may have reflected his early training with George Loring Brown, who it was felt taught the artist "the importance of the minutiae of forms in trees, shrubs and the earth itself, the shapes and densities of clouds, the structure, in short, of the visible world." Metcalf's paintings of New England have frequently been compared to the American poet, Robert Frost. In his eulogy to the artist, Royal Cortissoz offers a perceptive analysis into this aspect of his landscapes. Metcalf, he felt, painted "with a deep sympathy. He was not a dreamer. He never poeticised his subject. But with sensitiveness, with insight, he plucked the heart out of the scene he set himself to depict [...] He would more than paint a portrait of a place. He would so interpret it that it disclosed the essence of our countryside everywhere."

Kenneth W. Maddox

The Picnic, with its number of leisurely celebrants, is somewhat unusual for Metcalf, who has been characterised as depicting "the pure landscape with only now and then the rarest and faintest suggestion of the figure." With its screen of attenuated trees in the foreground through which the distant landscape is glimpsed, the painting resembles both The Golden Screen, 1906 (Washington, DC, Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution) and Dogwood Blossoms, 1906 (Private Collection). While his paintings in 1905-1906 were found to exhibit a "particular joyousness, " which was "expressed vigorously in the flowers that bloom in profusion, " The Picnic, with its touch of autumnal colouring, hints at a sense of melancholy. The picnic, a communal activity filled with social camaraderie, is instead portrayed with figures that seem isolated and estranged from each other. The quadrant of sunlit clearing is empty, the picnickers are pushed to the edges. The central figure stares vacantly towards the viewer. As Catherine Beach Ely has asked: "Is the wistful quality faintly tinged with sadness which seems to emanate from his pictures inherent in the artist or in the scene he portrays?"

Metcalf's canvas was painted shortly after a traumatic period in the artist's life. In 1906 he had realised his first substantial economic success as a painter. But while at the Old Lyme art colony the following year, he became anti-social, withdrawing into his room, as he realised that his wife was becoming increasingly involved with his former student, Robert Nisbet. They ran away together in July, causing a great scandal which forced Metcalf to leave Old Lyme. Metcalf, embarrassed by the incident, left the artists' colony, travelling through New England for the rest of the summer. He returned to Old Lyme in September, and it was probably then that he painted The Picnic.

Metcalf has been considered the single American Impressionist who captured the essence of the American landscape. This may have reflected his early training with George Loring Brown, who it was felt taught the artist "the importance of the minutiae of forms in trees, shrubs and the earth itself, the shapes and densities of clouds, the structure, in short, of the visible world." Metcalf's paintings of New England have frequently been compared to the American poet, Robert Frost. In his eulogy to the artist, Royal Cortissoz offers a perceptive analysis into this aspect of his landscapes. Metcalf, he felt, painted "with a deep sympathy. He was not a dreamer. He never poeticised his subject. But with sensitiveness, with insight, he plucked the heart out of the scene he set himself to depict [...] He would more than paint a portrait of a place. He would so interpret it that it disclosed the essence of our countryside everywhere."

Kenneth W. Maddox