Terraphilia

Beyond the Human in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collections

In what ways can love reshape how we live with the Earth? Terraphilia invites us to reimagine our place on the planet—not as sovereigns or distant observers, but as companions in a shared world. Through art, philosophy, and ancestral knowledge, this exhibition explores how love of/for the Earth is a way of being and participating that can inspire justice, community, and care across species and time.

Terraphilia

A term combining the Greek philia (love) and the Latin terra (Earth)—expresses a deep emotional, ethical, and spiritual connection with the planet. More than a love of nature, it suggests an affectionate and transformative relationship with Earth. This kind of love is not centered on individual passion or romantic ideals, but on care, commitment, and responsibility toward all beings—human and more-than-human alike.

Historically, thinkers like the medieval mystic Ramon Llull envisioned love as a universal, divine force that binds the cosmos together, extending from roots to branches, from humans to animals, and to the Earth itself. In the political realm, philosopher Hannah Arendt spoke of amor mundi, the “love of the world,” as a way of building communities and preserving shared meaning. Yet both visions— mystical and civic—often excluded the Earth

as an active participant in that love.

In response, contemporary thinkers such as Malcom Ferdinand propose a new metaphor: the “World-Ship,” a collective vessel holding not just humans, but plants, animals, ecosystems, and diverse—historically and systemically excluded—cultural worldviews.

This perspective bridges the divide between Earth and world, urging us to see ecological collapse not only as an environmental crisis, but as a rupture in our shared capacity to live together on the same planet.

bell hooks, writing from the red clay of Kentucky, reminds us that Earth is not merely a backdrop to human life but our first and final homeplace. The Earth bears witness to lives denied justice, offering solace, dignity, and a sense of wholeness where human systems failed. This Black feminist vision of Terraphilia binds the spiritual and the material, the ancestral and the ecological, in an ethic of care that emerges from struggle and endures through memory.

Artists, poets and philosophers invite us to reflect on the historical weight of this rupture— how the same metaphors that once symbolized salvation, like the ship, also tell stories of exclusion, empire, and exploitation. And yet, through imagination, ritual, and remembrance, communities continue to resist, reclaim, and remake their place within the planetary commons. Terraphilia, then, is not simply an idea—it is a pedagogical tool, a political practice, and a poetic vision.

This layered approach is mirrored in an architectural intervention by Marina Otero Verzier with Andrea Muniáin: a serpent-like, translucent structure that wraps around the exhibition space, guiding visitors through its shifting planes of transparency and interwoven scenarios. In a time of planetary crisis, Terraphilia reminds us that love can be a reparative force for reconnecting the broken threads of our shared world.

Cosmograms

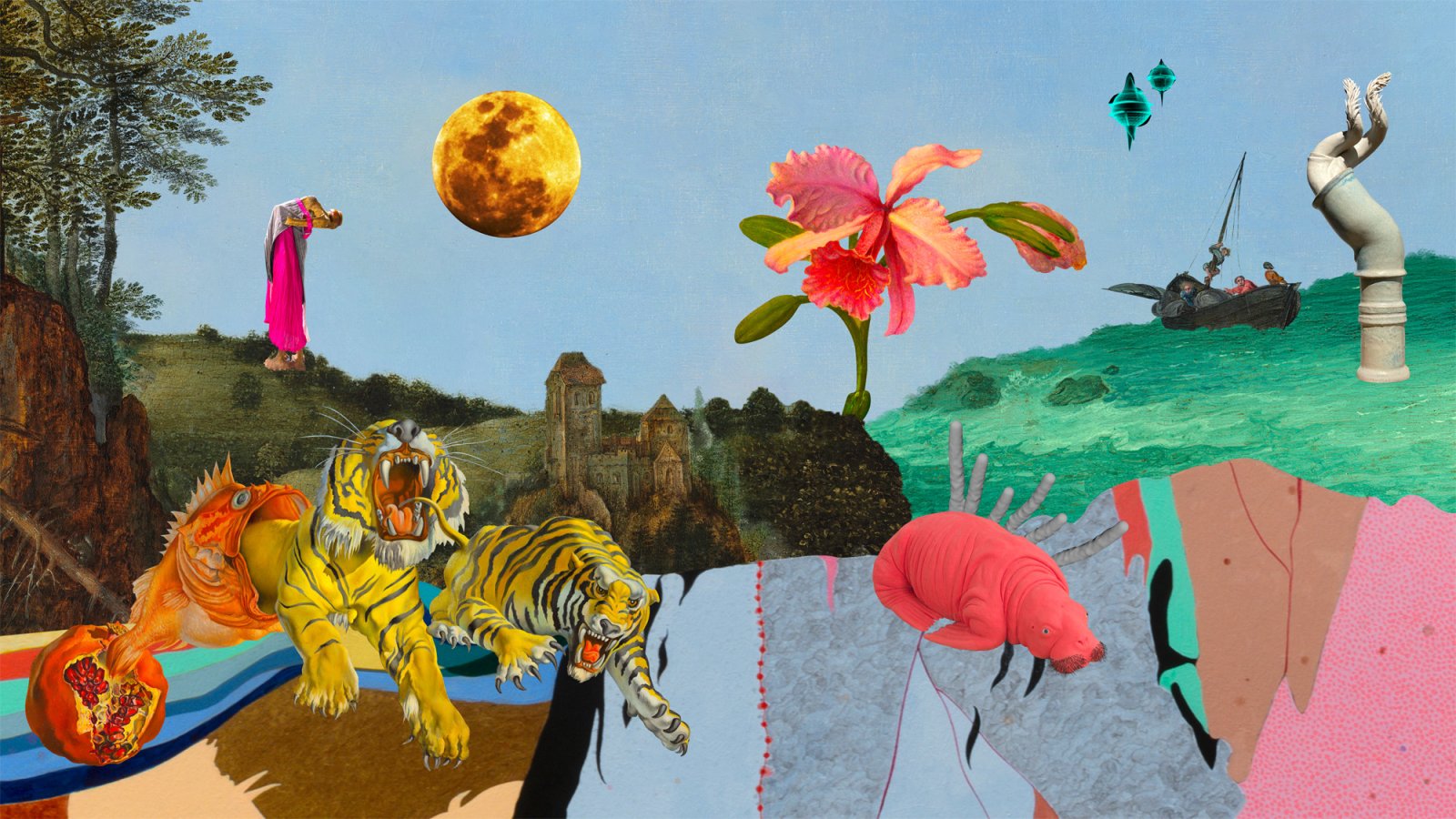

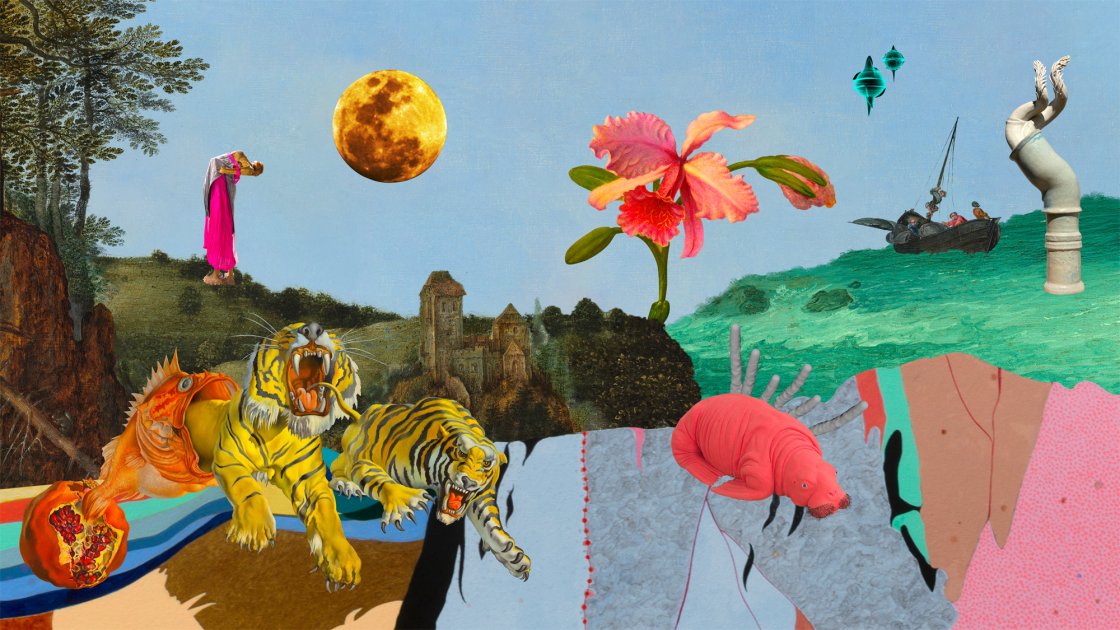

The ancient idea of the cosmos—an ordered whole that expresses a fundamental oneness or the ultimate reality—emerged across cultures to explain existence. These early cosmologies translated this sense of unity into concrete representations: myths, rituals, symbols, and diagrams that mapped relations between worlds and its inhabitants. Dr. Lakra's site-specific installation Monomyth, greeting visitors at the entrance to Terraphilia, stages a riotous parade of totemic figures—part human, part animal, part object, part spirit. Through playful acts of recombination and material mischief, these hybrid beings blur categories, unsettle hierarchies, and usher us into a world where transformation rules.

1. What is a cosmos?

The word cosmos originally meant “good order” or a “beautiful arrangement.” Ancient Greeks used it to describe not just the universe, but the deep harmony they perceived in the natural world. Across cultures and spiritual traditions— from Sufism’s al-Haqq to Hinduism’s Brahman— this sense of universal connectedness continues to shape how people imagine the world and our place within it.

We all live in a cosmos, but how we understand that the cosmos is shaped by culture, philosophy, and imagination.

2. Assemblages over systems

Rather than viewing the world as a system with clear hierarchies, we propose understanding it as an assemblage: the idea that life is made not from top-down order, but from alliances, relationships, and the symbiotic co-functioning between things.

Occupying a threshold of spiritual intensity and playful subversion, Dr. Lakra's Monomyth reveals difference not as division, but as a generative space of exchange, where cosmologies encounter one another through embodiment and transformation

This view helps us understand the planet not as a machine but as a dynamic, co-created web of beings —from fungi and humans to weather and myths.

3. Cosmologies shape our worldviews

A cosmology is a culturally specific framework for understanding the universe. It can be scientific, philosophical, spiritual, or mythological—but it's always a way of defining who or what belongs, and what is left out. Cosmologies are made tangible through stories, rituals, images, and artworks.

Every culture has its own cosmology, and every artwork contains clues about how the world is imagined, ordered, and lived in.

4. Who gets to be visible in the cosmic story?

Modern science and politics have long excluded nonhuman beings, denying them participation in the realm of the public and in politics. The exhibition challenges this by proposing planetary narratives—where animals, spirits, plants, and matter also have a right to belong.

To live together differently, we must first see each other differently—including the more-than-human.

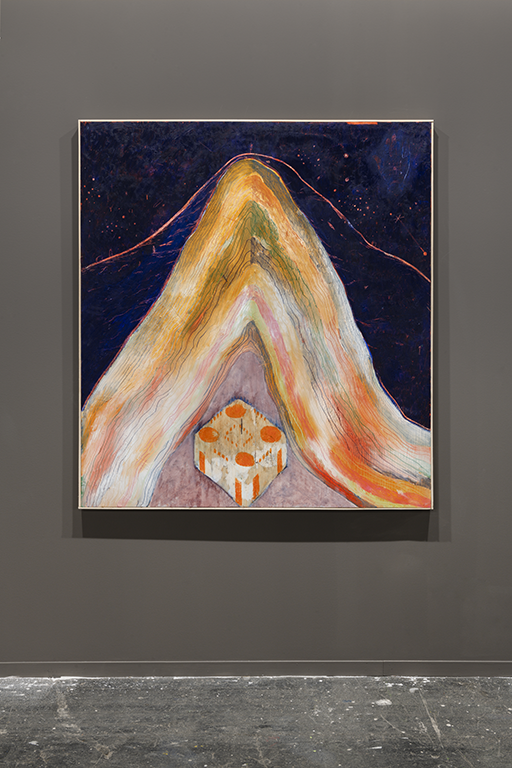

5. Cosmograms: visual maps of the universe

Cosmograms are artworks that show how people organize their understanding of the universe, and shed light on the ways in which diverse conceptions of the order and constitution of reality are woven into objects and practices. They take many different forms, from creation stories, magical-spiritual beings, landscapes, deities, or mythic figures.

Instead of asking “What is this?” we ask: “What kind of world does this artwork imagine?”

6. From landscapes to worldscapes

In the European tradition, certain landscapes— like the Weltlandschaften, world landscapes— compress the world into a single, panoramic view. Often serving as settings for mythical narratives, these works translate the vastness of the world into a legible whole, shaped by emerging humanist techniques like cartography and astronomy.

Art can help us see the planet not just as a surface to observe, but as a living field of relations and stories.

7. Dr. Lakra’s mythical collages

Dr. Lakra’s work transforms vintage scientific and ethnographic images into vibrant cosmograms of magical beings, deities, and hybrid creatures. These power-figures mediate between species and move across worlds and underworlds.

These works playfully dismantle the idea of a single, knowable reality, making space for plural truths and unpredictable encounters.

The Animated World

“The Animated World” invites us to think ecologically—not just about the environment, but about your place within a vast web of life. Drawing from science, Indigenous knowledge, and myth, this chapter shows what life does, and how its doing is one of connection, interdependency, and mutual co-constitution: everything as a connected one, from bacteria to spirits, from trees to tricksters. It considers what unfolds when we stop seeing the Earth as background and begin to encounter it as alive, intelligent, and teeming with unexpected companions.

1. Ecological thinking is multidimensional

When we think ecologically, we’re invited to imagine life not just at one scale or moment, but across many layers of time and space— from bacteria to forests, from the distant past to our present crisis. Ecology is not just science —it’s a way of sensing how everything is connected.

This view helps us understand how humans, animals, plants, microbes, and even minerals are interwoven in shared systems of life.

2. Life evolves through cooperation, not just competition

Inspired by the work of microbiologist Lynn Margulis, the exhibition shifts away from the idea of “survival of the fittest” toward one of symbiosis and cooperation. Life evolved from billions of years of interactions among microbes and gene transfers to create new cell and even species.

This challenges the Western emphasis on competition and hierarchy, and replaces it with a story of mutual aid, interdependence, and creative co-existence.

3. You are not one—you are many

Each human is a holobiont: a community of organisms living together—bacteria, fungi, viruses—all forming what we call “you.” Individuality, in this view, is not fixed. It’s shared and reveals an evolutionary continuity between the animal, plant, mycelial, and even mineral worlds.

We’re not separate from nature—we are nature, made up of countless living beings collaborating within us.

4. Plants and trees communicate and cooperate

Trees and plants aren’t passive. They sense, share, warn, and heal. Underground fungal networks connect forests like neural systems. Some trees send nutrients to their offspring or warn neighbors of predators.

Science and Indigenous knowledge converge to show that the vegetal world is alive with intelligence, emotion, and relationality.

5. More-than-human societies exist

In many Indigenous cultures, animals, plants, spirits, and natural forces are invested with personhood—beings with agency, intelligence, and emotions. These more-than-human entities are not symbolic; they are relatives, companions, and collaborators in life.

This perspective expands our idea of society and urges us to reconsider who belongs in our political, ethical, and emotional communities.

6. Shape-shifting, trickster beings break the rules

In traditional stories from around the world, we meet cross-beings—figures who are both animal and human, spirit and matter. They defy binary thinking, blur boundaries, and reveal new paths of understanding. They don’t follow the rules—they question them. They use metamorphosis, the change of appearance and shape, for the purposes of interspecies communication.

These characters show us how storytelling and myth can be tools for resistance, transformation, and imagination, especially in times of ecological and social upheaval.

7. Chimeras and composite beings: symbols of possibilit

Beings that blend human, animal, and plant forms—like chimeras—embody the fluidity of identity and nature. They invite us to embrace complexity and the fertile space between boundaries, where transformation happens.

Chimeras challenge our fixed categories and remind us that identity, nature, and meaning are always in flux. They show us that new worlds emerge through crossing lines.

8. Animism is a relational worldview

Animism—based on the worldview that all things have spirit or life—is not only a belief in magic, but a way of being based on respect and relationships. It recognizes that stones, rivers, spirits, and ancestors are all part of our shared story and are capable of exchanging significant messages with each other, accessing similar faculties.

Animism teaches us to listen, to live responsibly, and to value the intelligence of the Earth itself.

The Art of Dreams

“The Art of Dreams” invites you to step into the other side of consciousness—where logic gives way to metamorphosis, and clarity emerges from the shadow to disturb the order-world. From ancestral visions to mystical epiphanies, dreams have always connected humans to forces beyond the visible world—serving not only as portals of encounter, but also as sources of wisdom. This chapter explores dreaming as a powerful form of knowledge, transformation, and resistance—one that reshapes how we conceive time, self, and the cosmos.

1. The dream’s portal

Being alive on this planet is not merely about exerting agency upon the world, but about attuning to it—moving with its rhythms and participating in its cycles. Our bodies and minds pulse with natural cadences: light and darkness, seasons and stars. As day dissolves into night, we enter another temporal stratum—the realm of dreams, where intuition, memory, and transformation coalesce.

The night is not just the absence of light, but a gateway to inner vision, spiritual connection, and creative possibility.

2. Dreaming is a way of knowing

Dreams offer a type of knowledge that isn’t rational or linear. They don’t send messages in the traditional sense, but create experiences of communion to receive guidance and insight into the unseen. This is a poetic, intuitive, and mystical form of understanding.

Dreams are not “escapes” from reality—they’re alternative ways of making sense of life, death, time, and being.

3. Metamorphosis is the language of the dreaming world

In dreams, forms shift, boundaries blur, and beings transform. Like in Auguste Rodin’s The Dream, where two figures seem to emerge from marble, dreams often reveal the fluid nature of existence—where the material and the spiritual are intertwined.

Dreaming reminds us that nothing is fixed: identity, form, and knowledge are always in motion.

4. Visions can lead to revelation

Throughout history, mystics, seers, and prophets have stepped away from daily life— retreating into solitude to access deeper insight. This withdrawal opens a channel for visions, revelations, or even unsettling truths to emerge from the imaginary or the cosmic.

Sometimes, stepping outside of the visible world allows us to “see” more clearly what lies within or beyond it.

5. Dreams connect us to ancestry and the spirit world

In Aboriginal Australian cosmology, dreamtime is not just a time of sleep—it’s a sacred dimension where ancestral spirits and creation stories continue to unfold. Similarly, in Cameroonian artist Hervé Yamguen’s paintings, dreamers are vessels of sacred forces, accessing the “great mystery” of being.

Across cultures, dreaming is a bridge between the individual and the collective, the past and the future, the human and the more-than-human.

6. Dreams as resistance and reimagination

Dreams can unsettle, disturb, and even resist the “order” imposed by society, science, or convention. In this way, dreaming can become a form of rebellion, a way of imagining other worlds or liberated futures that don’t yet exist.

In times of uncertainty, dreaming can be a radical act of imagination, a refusal to accept the world as it is, a direct response to societal norms.

7. Expert dreamers: the Surrealists

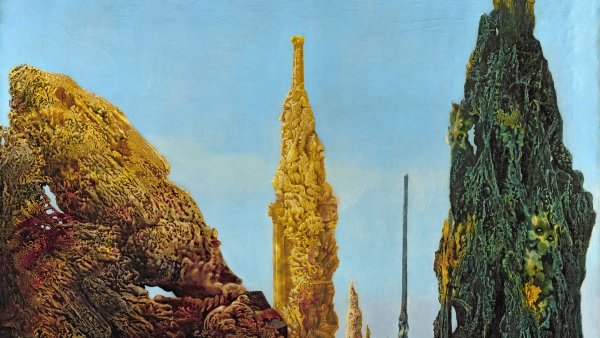

In the early twentieth century, the Surrealists turned to dreams not as escapes from reality, but as methods of rupture—tools for unsettling bourgeois reason and repressive order. They believed the unconscious held revolutionary potential, where repressed desires and forgotten cosmologies might resurface. Dreaming, for them, was not merely personal but political.

The Surrealists remind us that to dream is to unlearn what has been imposed and to trace the contours of what might still be possible. In a time of planetary crisis, expert dreaming may again become a political act.

The Objective World

“The Objective World” explores how rational thinkers sought to understand and control nature—through science, logic, and the tools of observation and classification. But behind the stillness of scientific order lies a story of exclusion and resistance.

This chapter asks: What happens when we try to freeze life in place? Who and what gets left out? And what other ways of knowing might still be waiting in the wings?”

1. Knowledge as power: the scholar’s still life

Corner of a Library shows globes, maps, and scientific tools and evokes the world of the Enlightenment scholar—detached, thoughtful, surrounded by devices of observation and learning. This “silent dialogue” represents the belief that truth could be established through study, reason, and order.

The claim of objectivity is human’s ability to comprehend the world and the laws of nature from “outside.” It also meant that any other way to understand and interact with the world became obsolete and was fiercely subjugated.

2. The cosmos as a rational machine

Enlightenment science aimed to uncover a logical structure behind all existence. Nature was reimagined as something systematic and knowable—turning mystery into mechanism, and insisting on a hierarchy of being with God atop, followed by humans, then animals, and lastly by all others.

Is knowledge produced to better understand the world—or to dominate or regulate it? To broaden perspectives—or to reinforce existing worldviews and sustain a particular political-economic status quo? Exclusionary types of knowledge erase, divide, and exploit.

3. Order vs. the Wild

In Melchior de Hondecoeter’s Landscape with Poultry and Birds of Prey, well-groomed chickens clash violently with untamed birds of prey—a metaphor for the battle between civilized control and unruly nature. The “wild” was associated with danger, otherness, and disorder—often projected onto stigmatized and gendered bodies and non-Western cultures.

This shift laid the foundation for modern science, but also for a loss of connection to the wild, spiritual, and intuitive aspects of nature.

4. The urge to catalogue and contain

Driven by curiosity and conquest, early scientists collected and classified plants, minerals, and animals from around the world. Nature was immobilized—pinned in herbariums, preserved in still lifes—as part of an effort to catalogue and extract its commodity values.

These practices helped build modern science—but also reflected a desire to own, define, and dominate the natural world.

5. The tools of discovery

Astronomers and explorers used instruments like telescopes, quadrants, and chronometers to track stars and map the Earth. But scientific progress was never a straight line—it was a story of trial and error, dead ends, and moments of accidental brilliance.

The Enlightenment wasn’t just about answers—it was about the messy, human process of trying to understand a complex world.

6. Troubling objectivity on its own ground

In Skipholt, John Bock satirizes the heroic figure of the explorer-naturalist, turning expedition into a performance of farce and failure. Thomas Ruff’s Sterne series reclaims astronomical negatives, shifting their meaning from data to cosmic enigma. In New Berlin Sphere, Olafur Eliasson uses light and geometry to create a perceptual field in constant flux—disrupting the illusion of objectivity as stable truth.

Knowledge is a fickle thing. We can’t really qualify or quantify it in absolute terms. Is more knowledge always better than less? What counts as good knowledge? Today, we undeniably live in an era of unprecedented knowledge production, with extremely efficient technologies for generating and disseminating it. Is this enough? And... have we reckon with the legacy of the excesses of rationalism?

Terra Infirma

“Terra Infirma” invites you to step to an unstable ground, where land is not a possession but a living archive of the traces of colonization, resistance, and renewal. This chapter examines how the Earth itself bears witness to histories of dispossession and survival. Through totems, soil samples, creation stories, and acts of protest against extractive violence, the artworks here challenge inherited notions of land as property, calling instead for a renewed ethic of kinship, reciprocity, and care.

1. The Earth as witness

The ground beneath us is alive, carrying the traces of births, migrations, and wounds. In many cosmologies, earth, rock, and clay are not inert substances but sentient matter— ancestors and witnesses that hold the pulse of time. They are both origin and archive, vessels of what persists and what was once nearly lost.

The land carries stories that official histories neglect. Its textures, fractures, and layers hold the memory of creation, survival, and disappearance.

2. Terra Infirma: the unstable ground

Terra Infirma speaks of a planet marked by extraction, conquest, and rupture. Against the legal and colonial concept of “terra firma”—as Carl Schmitt described, a world divided, bordered, and owned by those deemed fully human—this is a terrain of uncertainty and restless memory. The earth here is not backdrop but active force, unstable and aware.

Recognizing land as sensitive, reactive matter unsettles the logic of ownership and redraws the map of relation.

3. Earth cosmologies

Across cultures, stories speak of life coaxed from clay, minerals, and dust. From the use of protective amulets in Burma to Ana Mendieta’s earthly imprints, these gestures carry an ancient intimacy with mineral matter. Earth is not passive ground but a co-creator of life, a medium where body and soil, spirit and sediment, interweave.

Ancient stories of creation remind us that the ground is never mute. It shapes bodies, beliefs, and the unseen worlds they move through.

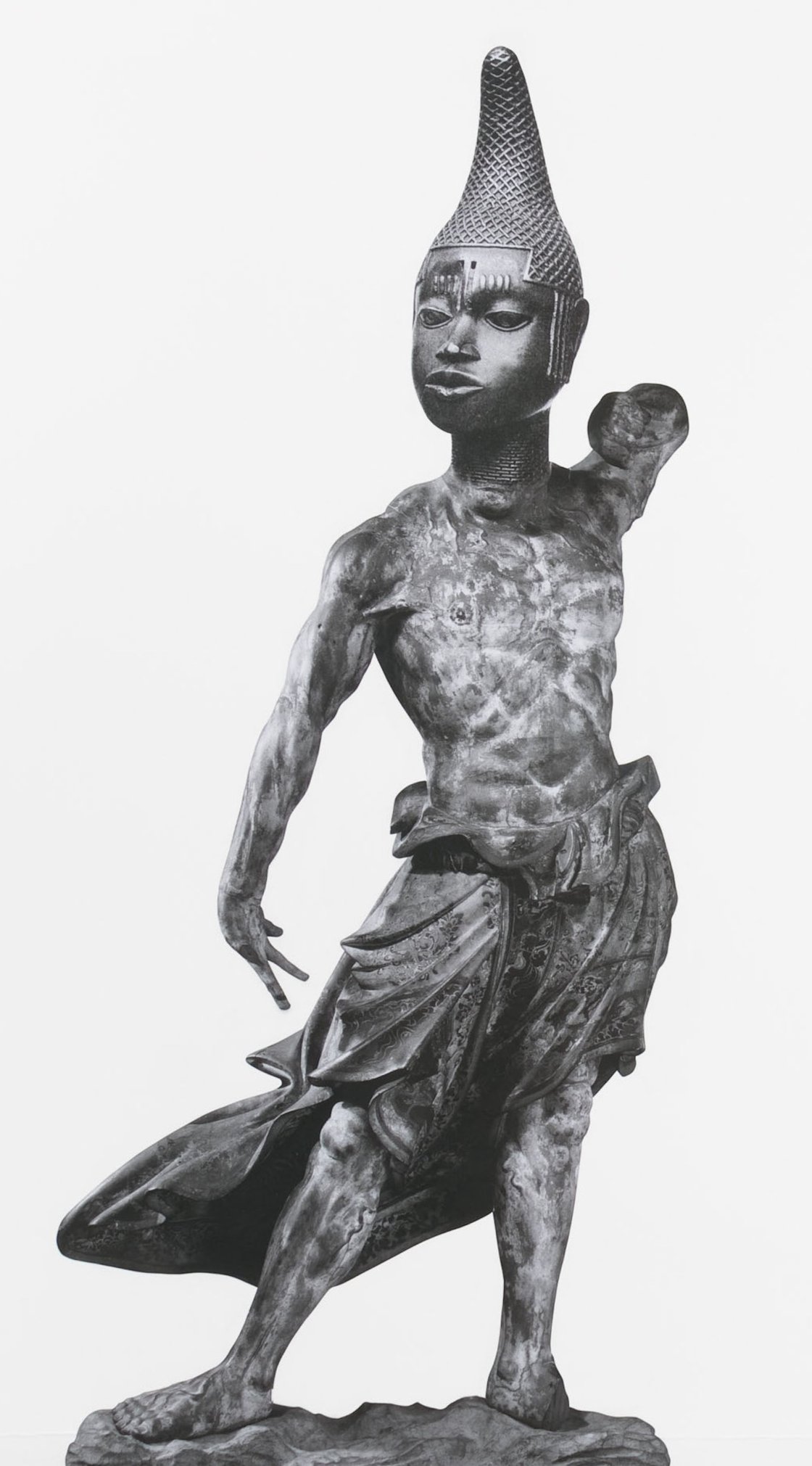

4. Totemic figures, gathering presences

In Brad Kahlhamer’s constellations of prairie girls, animals, and ancestral spirits, or Daniel Otero Torres’ totemic tributes to land defenders, figures emerge that hold together the living and the lost. They are not monuments to the past but gatherings of hybrid, insurgent, and enduring presences.

Holding the space for figures that have been violently muted is an act of memory and healing— they embody plural identities that refuse colonial erasure.

5. Landscapes as tools of empire

Though they appear idyllic, landscapes often conceal histories of dispossession and conquest. Paintings like Albert Bierstadt’s Sundown at Yosemite cast stolen territories in the glow of pastoral beauty, turning them into speculative commodities and tools of colonial desire. Aesthetic splendor becomes a strategy of erasure.

Art isn’t always innocent—it can reinforce systems of power and erasure, especially in the context of land, race, and empire and uncovering such entanglements with power reclaims the stories the powerful have sought to displace.

6. Soil as an archive of violence

Through Dineo Seshee Bopape’s scorched earth and Hervé Yamguen’s restless ancestral skulls, the land reveals itself as a custodian of trauma and rebellion. Soil absorbs what is buried and what remains unresolved, carrying traces of forced migrations, uprisings, and spirits denied rest.

The earth remembers. It holds traces of harm and resistance, urging reckoning where official narratives fall silent.

7. World-building through land relations

Drawing on decolonial thought and Indigenous cosmologies, this chapter foregrounds land as a relation, inhabited by spirits and the resting place of the living and the dead. The works gathered here imagine planetary futures woven through ecology, justice, and care—where the Earth is a shared commons, never a possession, and the ground from which worlds are built.

Repair begins with how we listen to land. Honoring Indigenous land relations as both an ontological necessity and a political act affirms land as the living ground for resistance, reciprocity, and the shaping of just futures.

The return of the Time of the Myth

Myths shape who we are and how we relate to the world. From stories of creation and exile to objects embodying sacred powers, myth emerges as a living force that helps communities endure, transform, and remake their worlds. This chapter invites you to meet ancestors, mythical figures, and spirits-beings, who dwell in the space between the known and the unknown, guiding us through times of crisis and change.

1. Myths anchor us in the world

Myths are living stories that shape how we understand ourselves, our origins, and our place in the world. They are not just ancient tales but ongoing narratives that anchor identity, reveal values, and map how the world comes to be and how this order must be maintained. Our ability to create myths is a means through which we envision and call forth relations that are not yet present.

Myths build belonging and meaning. They remind us who we are, what we cherish, and how we relate to the world and each other.

2. Mythical time awakens in crisis

Mythical time moves beyond linear history—it is cyclical and recurrent. It surfaces whenever the present falters or calls for renewal, offering pathways to reimagine and rebuild collective life and purpose. Unlike historical time, which seeks order and continuity, mythical time embraces instability: animals speak, gods descend, and species intermingle.

Myths don’t just recall the past—they activate transformation, helping communities heal, adapt, and dream new possibilities.

3. The Door of No Return

The myth of The Garden of Eden and the Fall of Man has long served as a story of exile and loss. In Expulsion. Moon and Firelight, Thomas Cole stages this rupture with stark contrast: Eden glows on one side, while a shadowed world of fire and cavern engulfs the other.

The “door of no return” also names the final threshold in West African slave forts, where millions were forced onto ships bound for enslavement in the Americas. These doors mark not just physical departure, but metaphysical severance—a crossing into displacement, violence, and survival.

To remember the door of no return is to confront the enduring myths and realities of forced exile, and to honor the afterlives of rupture etched into bodies, geographies, and collective memory.

4. Paradise Reframed

Colonial powers recast conquered lands as earthly paradises—fertile, ordered, and divinely destined for European rule. Under the emblem of the cross, conquest was framed as cultivation, and conversion as salvation. Visual and narrative fictions portrayed harmony among colonizers, Indigenous peoples, and the enslaved—masking violence, dispossession, and resistance. These new myths transformed brutal occupation into a sacred mission.

Myths such as Earthly Paradise and the Promised Land can be used to justify conquest—recasting domination as harmony, and erasure as divine inheritance.

5. Candomblé and resistance through ritual

Candomblé is a spiritual tradition born of African heritage and diasporic survival. Developed during slavery and colonial violence, it served as a mythopoetic act of resistance —a way for enslaved people to preserve identity, forge community, and reclaim dignity.

These practices honor the living and the dead, nurturing solidarity and renewal through embodied remembrance.

6. The Sacred Embrace

Myth is a sacred opening through which cosmic energies enter form—infusing matter, ritual, and symbol with transformative force. The Mandala of Chakrasamvara makes this visible. When closed, it appears as a lotus bud; when opened, it reveals a cosmos in bloom, with, at its center, the sacred embrace of wisdom and compassionate action, a state of enlightened awareness that dissolves the illusion of separateness.

In a time marked by fragmentation and disembodiment, the mandala affirms union as a principle of transformation. It encodes a mythical act of love and passion into a luminous, timeless form.

Oceanic Cosmogonies

A cosmogony is a theory or story about the origins of the universe and life. This chapter explores oceanic creation stories that begin with the emergence of life in water, through motion and interconnection.

Blending ecological science with myth and spiritual practice, it invites us to enter the world through the sea’s perspective: to sense with the currents, to move with the plankton, and to carry memory in every drop of salt water.

1. The ocean as a space of fluid knowing

The ocean’s turbulent, refractive waters dissolve boundaries between body and environment. Its shifting forces invite a fluid, undisciplined way of thinking that enfolds mind and body. Inspired by ecology, Indigenous epistemologies, and science fiction, “wet ontologies” explore the world as interconnected flows.

The ocean becomes a metaphor and a method— offering a “wet” form of knowledge that moves across bodies, disciplines, and ways of being.

2. Thinking with the ocean is transformative

To think “oceanically” is to dive into the deep and to let go of a terracentric understanding of the world. It means embracing complexity, uncertainty, and constant movement—between science and myth, ecology and imagination, life and matter.

The ocean isn’t just something to study—it’s something to think with, offering new ways of imagining relationships between humans and the planet.

3. Oceanic myths and new creation stories

Artists like Josèfa Ntjam draw on the African spiritual figure of Mami Wata and marine biology to create new myths of becoming—where hybrid beings born from the sea connect us to both ancient origins and speculative futures. Similarly, The Otolith Group’s Hydra Decapita immerses the viewer in oceanic cosmogonies intricately entwined with African and Black histories. The film evokes an imagined underwater society, animated by ancestral memories and haunted by the spectral presence of Africans cast into the sea during the transatlantic slave trade.

These stories reclaim water as a living archive of memory, trauma, and submerged histories— revealing the sea as a site for ancestral knowledge and futures beyond colonial violence.

4. Galatea: becoming with the sea

Galatea drifts between sea and sky, myth and flesh. She is neither fully human nor wholly divine, but suspended—emergent. Her body, shaped by longing and oceanic force, resists the fixed forms of identity. To read Galatea through a transfeminist lens is to see her as a figure of aqueous subjectivity—fluid, relational, always in transformation. She teaches us that to be shaped by the sea is to live in motion, in multiplicity, in permeability.

Transformation is not new—it’s ancient. Myths show that fluid becoming has always been part of how we imagine life, desire, and the sexual body. In invoking these stories, we remember that change is not deviation but a deep, ancestral logic of existence.

5. Bodies of water are trans* archives

We are all connected through water, yet we are not the same. Water remembers. Like the bodies that move through and with it, water is porous, leaky, transitional. It archives not by containment, but through flow—tracing what was, what persists, and what is still becoming. To call water a trans* archive is to recognize its holding of gendered, racialized, and ecological transformations.

Water is not just symbolic—it’s a living archive, a force that teaches us how to be together across species and scales. Transfeminist vision shows how bodies of water inspire us to rethink identity as dynamic and interconnected, reminding us that we are shaped by the currents that surround us.

6. Creatures of the deep: allies and warnings

From jellyfish to zooplankton, gelatinous sea life is thriving in increasingly toxic waters. Some of these beings mesmerize with their fragile forms —yet they signal ecological imbalance and the rise of resilient lifeforms in collapsing ecosystems.

These species remind us of what thrives when ecosystems fail—and invite us to reflect, and feel awe and concern, about our role in that shift.

7. Toward an aquatic consciousness

Susanne Winterling’s Planetary Opera and similar immersive works dissolve the boundaries between ocean, cosmos, science, and emotion through light, sound, and sensation. They invite viewers to enter the fluid realm of watery life, sensing its rhythms and mysteries from within.

This art doesn’t merely depict the ocean—it calls us to experience being water itself, cultivating a deep, embodied connection that reshapes how we relate to the planet and its many forms of life.

Sissel Tolaas Wherearewearewhere

Sissel Tolaas has been commissioned by TBA21 to create an immersive installation that activates the exhibition through scent. Six olfactory compositions, evoking the elemental themes of Terraphilia–Ocean, Animal, Human, Stratosphere, Earth and Nature–are infused into a series of hand-blown glass vessels. These smellscapes transform the space into a dynamic, multisensory environment.

Each olfactory experience acts as a narrative, carrying traces of worlds beyond the human and connecting visitors with memories, emotions, and breathing sensory engagements. Tolaas’s smellscapes subtly interact with the visual components of the exhibition, blending and shifting the way art and space are experienced and remembered.

A commission, in this context, becomes a form of curatorial and institutional care: a gesture of trust in the artist’s vision to reimagine institutional space. It invites new ways of perceiving and relating between artwork, visitor, and environment.

1. Air is alive with memory

Sissel Tolaas treats air as a living archive, where each smell molecule is a unit of meaning, a trace of life encoded in chemistry. Smell, in this sense, is a mode of contact that exceeds language and perception. It arrives uninvited, settles in the lungs, enters the bloodstream, stirs memory, shifts attention: to breathe is to join an atmospheric continuum, one charged with entanglement, and reciprocity.

Each breath draws us into relation—with places we have not seen, species we do not know, and pasts that are not over. Smell becomes a way of remembering that bypasses representation and settles directly into sensation.

2. Smell is knowledge beyond words

By linking cognition to experience, Sissel Tolaas’s practice refuses the hierarchy that places rationality and language above the sensual. She also insists on the porous continuity between the self and the world. Smell carries meaning through its capacity to affect—to transform our sense of presence and position. In response to the difficulty of naming smells without collapsing it into cliché or metaphor, Sissel developed NASALO —a linguistic system built from the specificity of olfactory experience, rather than imposed categories. But even this system does not attempt to stabilize smell into fixed meaning. Instead, it expands the field of attention, allowing us to stay with sensation longer, more attentively, and more respectfully. In Tolaas’s practice meaning emerges in the act of breathing together: through presence, through exchange, through shared air.

This challenges dominant knowledge systems and reminds us that language is not the only way to think. Smell becomes a form of literacy in the archive of air.

3. The body is a porous sensor

Smelling unfolds through a shared atmosphere moving through and around us in waves. It meets the body as a continuous surface alive to sensation and as a catalyst to relation. Smell circulates with and through us, activating a kind of porous attention, one in which sensing and being sensed are part of the same unfolding process. These moments invite participation as part of the atmosphere itself.

Breathing becomes a form of co-composition, where air is shaped by every presence in the room. The breath of one contributes to the breath of many, affirming interconnectedness; forms of relation that arise through entanglement and mutualism.

The olfactory turns attention away from what is solid and stable, and toward what is mutable, diffuse, and shared. The body becomes an atmospheric sensor: a surface of encounter shaped by every molecule it meets.

4. Smell as history’s witness

Sissel Tolaas treats smell as evidence—chemical traces that hold the weight of past events. Working with molecules collected from conflict zones, polluted soils, archeological sites, or places touched by trauma, she uses smell as a forensic tool. These smells are material records of what has happened. Walls absorb violence, soil carries sorrow, and objects release memories through their chemistry.

The olfactory, in her practice, becomes a method of investigation. It moves beneath the surface, beyond what images or text can offer. Smell reveals what may have gone unspoken, unnoticed, or erased.

Smells can operate as a witness in conflicts, ecological disasters, or in archeological excavations. Sissel Tolaas’s olfactory practices throw open a radical path of understanding the past and how smell can have a role on solving uncertainty and misinformation.

Activities related to the exhibition