Edgar Degas. At the Milliner’s. Technical study of a pastel

El vídeo de arriba es para uso exclusivamente decorativo dentro de está página.

Technical studies and special display

The museum’s Restoration and Conservation Department has spent over a year conducting a technical study of Edgar Degas’s At the Milliner’s made possible by the sponsorship of the Fundación María Cristina Masaveu Peterson.

The aim of this work was to gain an overall understanding of the pastel painting technique used by Degas and to study this picture, painted in 1882, in greater depth using infrared reflectography, X-radiography, macro photography and laboratory analysis. This advanced technology has enabled us to identify the materials used and assess their state of conservation.

We could undoubtedly define Degas as an inquisitive man and a tireless investigator insofar as his art was concerned, because his work shows us that he employed multiple artistic techniques during his long life, and that his modus operandi evolved as he progressed as a painter.

The pastel painting technique

In his development as an artist, Degas recovered pastel. Although first mentioned by Leonardo da Vinci in the late fifteenth century, this technique did not flourish until the seventeenth century, when it was taken up by painters like Maurice Quentin de La Tour and Jean-Siméon Chardin, and after the French Revolution it was abandoned in favour of oil paint.

Degas explored pastel like no one before him, giving it a new life. He handled it in such a way that his works blur the boundaries between drawing and painting, his application of the colours making them fuse in the viewer’s eye.

He employed the technique in different ways, sometimes on its own, using only the pastel sticks, and sometimes as a mixed technique, combining the pastel with gouache or tempera, or crushing the sticks and mixing them with water to create a watercolour effect or achieve a pasty texture for the colour. Rather than following a standard pattern, his inquisitive mind prompted him to investigate constantly and to squeeze every possibility he could out of a few simple sticks of colour.

The execution of the pastel is admirable. Degas’s agile and vigorous handling of these sticks of colour enable him to recreate the different textures of the hats and the women’s clothes, in which we discern feathers, flowers and straw details; looking at the close-up images, we can also see how he superimposes the different layers of colour without mixing them, even though that is how they appear to our eyes.

This painstaking superimposition of layers is another hallmark of Degas the pastel artist, who in this late stage of his life had acquired an exceptional command of the technique.

For instance, if we look at the face of the woman trying on the hat, we see a delicate pinkish skin that we would describe as soft.

And yet, closer examination of the application of the colour in this area actually reveals an extremely interesting superimposition of layers of rapid, vigorous strokes.

To arrange the composition, Degas defines his drawing with light lines in certain areas, confidently marking the elements that form part of the work, while in other areas he subsequently interrupts or blurs the lines. There are even areas where he does neither one thing nor the other, opting instead to leave them completely unfinished or only slightly insinuated.

Chialiva and the fixative

The landscape and animal painter Luigi Chialiva relocated to France around 1872 and settled in Écouen, on the outskirts of Paris. He exhibited at the Salon and at the Société Nationale des Beaux Arts, to which he was admitted as member in 1912.

He trained as an architect but above all as a chemist, and it was this facet that enabled him to advise his friend Degas on his investigations of the pictorial techniques that interested him.

One of his goals in this respect was to paint using pastel exactly as he wanted, creating successive layers of colour. This meant fixing the layers, because otherwise he would merely end up smudging the colours.

Degas was not convinced by any of the fixatives on the market at the time because while they did fix, they altered the colours of the materials used, and he therefore ruled them out for his purposes. Chialiva managed to create a fixative that met the requirements sought by Degas, enabling him to use it without the slightest alteration to the natural colour of the pastel sticks, and certainly not to the matt appearance he was so keen to achieve, evidently fulfilling its basic fixative function.

«Degas unquestionably invented this application of successive layers of pastel in which each one is fixed before it is covered with the next. Apparently, it occurred to him that pastel could be adapted to serve a technique in which different colours act upon each other by superposition and transparency as much as by the opposition of juxtaposed tones». Since he was unable to work pastel in the same way as oil paint, the fixative meant that he could achieve an analogous effect to glazes by leaving some spaces uncovered so that the underlayers of colour peeked out.

Following our study of the pastel at the Museo Thyssen, we believe that Degas used the fixative to be able to work layer by layer. The fixative achieved the necessary effect for preserving intact the colours already applied while the artist completed his painting, enabling him to add as many layers as he wanted to superimpose the different colours and gradually create the desired volumes or effects.

The materials identified in the work

X-ray fluorescence (XRF) was the technique employed to analyse the pigments of the pastel sticks that Degas used in this work. Two facts were taken into account in the spectrum acquisition for each point analysed: the great variety of colours present in the work, and the diversity of strokes in the different forms that make up the composition.

In general, a wide variety of pigments was identified. The analyses corroborated that the final hues were obtained by superimposing strokes of varying colours, since this superimposition is the only explanation for the large quantity of elements detected in the XRF spectra for single points.

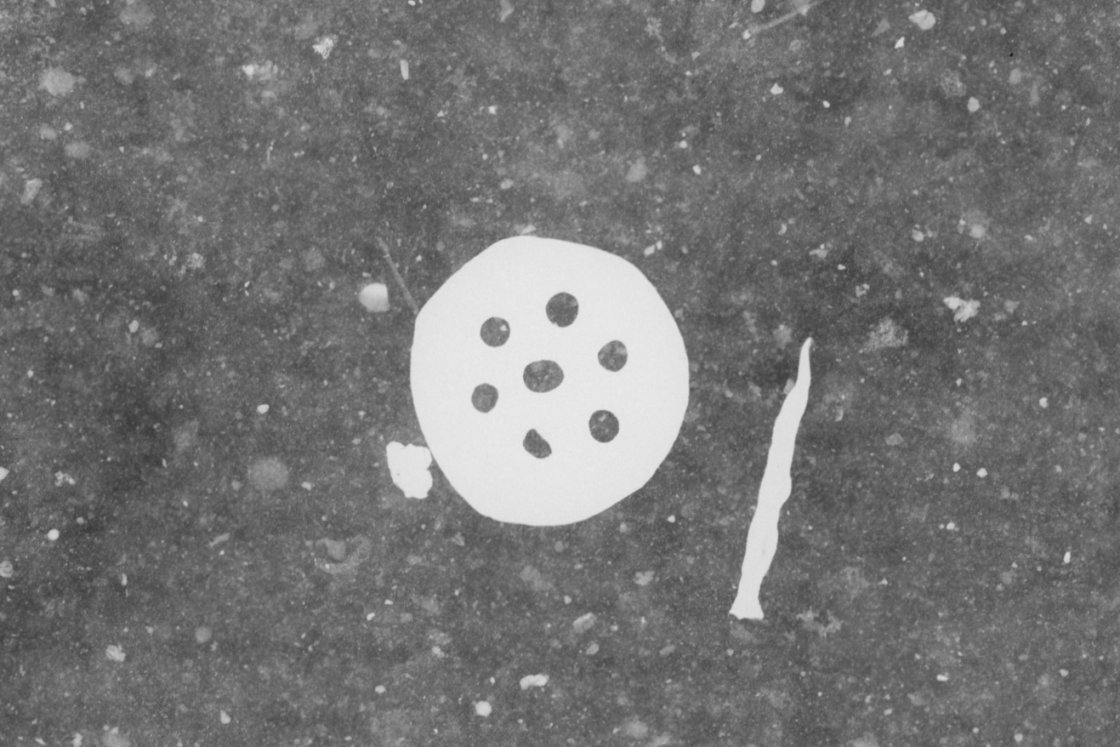

In addition, a micro-sample (taken with a 0.25 mm micro punch) was taken from one side of the painting, at a point where a black and red stroke invaded the unpainted area. The cross section of the micro-sample corroborated the presence of the pigments bone black and vermilion, this time using SEM-EDX.

The analysis of the cross section reveals certain details that enable us to formulate a hypothesis about the sequence of materials. For example, the image under ultraviolet light (UV) shows paper fibres with a slightly violet hue, some of them elongated and others with the fibres pointing to the viewer, according to their random position in the pulp that makes up the paper.

However, located between the paint (pastel) and the support is a continuous space, with a bluish fluorescence, that may suggest the presence of an organic material with a thickness that oscillates between 15 and 40 mm. The same bluish fluorescence is also observed on the surface in the form of an ultra-thin film with a thickness of 5 to 15 mm

The support

The work has preserved its original structure. In general, this is a semi-industrial mount comprising an ordinary industrial cardboard base approximately 7 mm thick and with a high grammage. The core of the support used by Degas is ordinary industrial cardboard to both sides of which countermounting paper with a turquoise-blue or blue-green coated finish was added.

This countermounting paper was glued to both sides of cardboard used as the support for artwork, binding and similar in order to prevent deformation. This meant that the carboard would not lose its shape or warp once the paper used for painting was added, like in this case.

The second element of the support is the paper on which Degas applied the pastel. Paper used as the support for this medium needs to have a rough, textured and unglazed finish (rather than polished and smooth) so that as the pastel stick is dragged over the surface it deposits pigment between the irregularities. This paper is placed over the carboard from the front, wraps around the reverse where it is affixed only with bands of gummed kraft paper.

On the front, the drawing paper is loose rather than affixed, and therefore secured only on the reverse.

This type of mount provided a smooth, taut support that was firm but lightweight to facilitate the application of the pigment with the pastel stick. It also fulfilled another aim: withstanding the moist casein without losing its shape. Lastly, the end result was a more robust finish for safer and more durable handling and framing.

The X-ray

The X-ray reveals that the support has a pattern of horizontal and vertical lines corresponding to the mechanical production of laid paper. These marks are formed when the paper pulp is placed on the mesh of the mould. The fine vertical lines are called wire lines and the thicker horizontal lines are called chain lines.

The paper pulp has been mechanically processed. The mixture was identified in the museum’s materials laboratory. Different X-ray-opaque particles can be seen. The material is heterogeneous and fairly unrefined, which could cause future conservation problems.

Esparto grass, straw and even fishing nets used to be employed for this purpose. In this case, fragments of very different materials can be seen, such as resin particles, probably from the gluing of the paper, and metal particles, which may be due to impurities in the water used to make the paper pulp or to residues from the metal mould. There is also evidence of fibres from the recycling of poorly shredded waste rags, as a button and the tip of some metal object are visible.

Conservation and treatment of the work

The paper of this work presented different areas of damage, especially at the corners and along the sides, with abrasions that amounted to tears and small losses of the support at some points, and in other cases to a slight weakening of the fibre network.

In certain areas, the interior of the cardboard was visible, as well as structural damage consisting in the separation of layers and losses of consistency.

The corners of the cardboard were reinforced with wheat starch, binding the layers and repositioning the angles in order to reinstate the torn fibres to their correct position.

Japanese paper (48 GSM) was grafted onto the angles and lateral cuts where losses of support had occurred.

Infrared reflectography

Together with materials analyses, technical studies are vital tools for obtaining scientifically proven data that enable us to investigate and examine an artist’s painting method. The combined use of these different study techniques is essential but, depending on the work in question, some furnish more information than others.

Slight adjustments are visible in the close-up infrared reflectograms. For example, starting at the left-hand side of the composition, we can see a pair of wavy lines on the hat stand that were ultimately moved further to the right. Another line on the left sleeve of the woman seated with her back to us tells us that this element of her clothing was previously a little wider.

The special display

This special display is designed to share the results of our research with viewers to enrich their knowledge of this complex artist’s working methods.This device shows the results of the technical study carried out by the museum's Restoration and Conservation Department on the pastel painting technique used by Edgar Degas in At the Milliner's.

Visitors are invited to explore the interactive display to gain an in-depth understanding of our work, which took just over a year to complete and examined the composition and texture of the support, the application of pigments, the luminosity of the colours and the way in which the strokes and layers are superimposed.