A Meteorological Tour of the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza

By José Miguel Viñas

The themed trails around the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza are an opportunity to explore its paintings from very different approaches and perspectives, all equally enriching. A careful look at the landscape paintings reveals that the skies depicted in most of them are far from being mere backdrops; in fact, in many cases they are an essential part or even the main feature of the composition on which the artist focused attention to give us enjoyment.

Clouds and other atmospheric elements that appear in paintings not only contribute to their beauty but can also tell us a lot. Dissecting paintings from a meteorologist’s viewpoint can teach us about the types of clouds found in them and even enable us to identify them with their proper Latin names (cumulus, cirrus, altostratus, cumulonimbus...). But it is just as, if not more, interesting to learn why particular artists repeatedly painted specific types of sky, which even became hallmarks of their style in some cases.

This complementary information is further enriched when we examine the weather and climate context in which these landscape paintings were produced. For although artists give free rein to their creativity, they follow trends and are influenced by others. This means that they inevitably reflect their own experiences in their works, and the environmental (atmospheric) component is always present, influencing the lives of each of them and each of us, everyone.

This trail will transport you to the majestic natural scenery of nineteenth-century America depicted by landscape artists such as George Innes, Albert Bierstadt and Martin Johnson Heade. Their masterful portrayals helped strengthen the sense of a national identity among the European settlers who progressively expanded across that vast territory. The harsh winters that Europe experienced during the Little Ice Age – chiefly between the 1500s and 1700s – are likewise reflected in paintings by Van Goyen and the Ruysdaels, among others. The skies of Van Gogh, Sisley and Boudin are also included in the tour, not to mention those of other Impressionist painters such as Monet and Pissarro, who were interested in capturing the spring thaw or how a snowfall transformed the landscape.

This original approach complements any other trail or trails visitors might choose. At the end of the tour, you will have more information with which to analyse particular landscapes, besides the satisfaction of contemplating the beauty of the works. The ultimate goal of this tour is to highlight the importance of the skies depicted in universal art and help visitors understand and enjoy them – both in paintings and in real life.

Starts on the second floor

On the map you can see the rooms where the masterworks are located.

The Massacre of the Innocents

The tour begins with a journey back in time to the second half of the 1500s, when much of Europe was shivering with cold, enduring harsh winters unlike anything witnessed in previous decades and centuries.

The Little Ice Age was underway: this is the name given to the abnormally cold period that Europe and other parts of the world experienced from the 1400s to the 1800s, with three peak moments when the intensity and duration of the low temperatures and bleak weather conditions severely tested the population. This climate anomaly was reflected in paintings.

A good example is this panel, executed in 1586, where Lucas van Valckenborch I (1530–1597), a Flemish artist living in Germany, depicted a religious theme linked to the Nativity of Jesus, setting the action in one of those freezing winters of the period. He was following in the footsteps of Pieter Bruegel the Elder, whose experience of the harsh winter of 1564–65 a couple of decades earlier led him to focus on and capture it in some of his most iconic paintings. Notable among these are Hunters in the Snow (1565) and the three on the theme of the Nativity, one of which, the Massacre of the Innocents (c. 1566), inspired Van Valckenborch I to paint his own version.

Bruegel made the harshness of winter the main feature of his landscapes and was copied by other painters who witnessed the cold weather firsthand, as can be seen here. The influence of the patriarch of the Bruegel family was not only pictorial but became embedded in the collective imaginary, as it profoundly changed the image people had had of Jesus’ birth in Bethlehem until then. Prior to his paintings the Nativity was set in springtime, with green fields and blue skies.

Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee

The rich variety of weather phenomena is one of the most striking features of this small painting by Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568–1625), the son of Pieter Bruegel the Elder, the patriarch of the well-known family of Flemish painters. The painting depicts a New Testament biblical scene in which Jesus, accompanied by eleven of his disciples, is travelling in a boat amid a violent storm.

The ‘sea’ where the action takes place is actually Lake Gennesaret or Tiberias, located in the region of Galilee – present-day Israel – 212 metres below sea level. Although the subjects of this painting are Jesus and the disciples accompanying him in the small boat that seem to be about to capsize, the choppy waters and the dark clouds covering part of the sky are also an important part of the scene.

Green, blue and grey tones are predominant, contrasting with the vibrant colours of the clothing worn by the people in the boat. Oblivious to the storm, Jesus is asleep, while the apostles are clearly distressed by the menacing tempest raging around them. Directly above Jesus, in a clear allegorical allusion, is a small fraction of the solar disc. Darkness – evil – is gaining ground and, continuing with the allegory, could eventually obscure the sun completely, consummating the victory of evil over good.

We also see light beams emerging from the right side of the cloud, and an area of sky on the left is illuminated by a bolt of lightning, a zigzagging electrical discharge triggered by the storm. The bluish colours of the sky also extend to the mountains in the background, whereas the wind-stirred surface of the lake – rich in nuances from the crests of the waves and the foam – is more greenish.

This tone lends considerable realism to the scene, as the sea turns green when a storm is brewing. Even so, in Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee the symbolic significance of the weather phenomenon takes precedence over any other consideration.

Winter Landscape with Figures on Ice

From the mid-1500s to the second half of the 1600s scenes of mid-winter – with snow and ice as the main features – became a recurring theme in European painting, especially Dutch.

The bitterly cold winters continued with a certain regularity during the Little Ice Age. These circumstances are fully reflected in the paintings of Dutch landscape artists of the time, such as Jacob Isaacksz. van Ruysdael, Hendrick Avercamp and Jan Josephsz. van Goyen (1596–1656). In this panel painting dated 1643 Van Goyen depicts the surroundings of Dordrecht, with the river frozen over and people going about their everyday lives and making their way on it. There are several horse-drawn sleighs, a few people skating and others engaged in various activities such as fishing or playing, as despite the hardship of these winters there was also time for leisure. These scenes were repeated over many winters.

Like other Dutch painters, Van Goyen emphasises the sky, which fills the upper two-thirds of the painting. Instead of being coloured the uniform grey characteristic of snowy weather, it is dominated by large cumulus clouds with a few glimpses of patches of blue in between. These clouds are infused with dynamism, an effect that is further enhanced by the movement of the people in the lower part of the painting.

Had those harsh winters not occurred, frozen landscapes would be absent from the oeuvre of Van Goyen and the many other painters who unwittingly acted as chroniclers of an era whose climate was the opposite of today’s (cooling versus warming).

Night: a Mediterranean Coast Scene with Fishermen and Boats

Painting night scenes poses greater technical difficulties than daytime landscapes, mainly because our vision diminishes when there is less atmospheric light. This distorts our perception of the colours and intensities of everything we see around us.

Even so, plenty of artists have successfully risen to this challenge, such as the Norwegian Romantic Johan Christian Claussen Dahl (1788–1857) and the French landscapist Claude-Joseph Vernet (1714–1789), who masterfully painted this beautiful nocturnal, moonlit seascape. Although the scene takes place at night, the picture is filled with light, owing no doubt to the influence that Vernet – like many other painters – received from Claude Lorrain (1600–1682) during his long stay in Italy.

THe established himself there as a painter of landscapes and seascapes, which earned him great international renown. After nearly two decades in Rome, shortly after returning to France in 1753 Vernet was commissioned by Louis XV to paint a series of fifteen pictures of the main French ports, one of his specialities. In this view of the Mediterranean coast, the ships’ rigging that can just be made out in the background mist in the most brightly lit part of the sea hints at the presence of a harbour.

The contrasts of light in this canvas are truly admirable. The artist includes three different light sources in the painting – the moon, the fire on the left and the flaming torch on the right – enabling viewers to appreciate a host of interesting details.

The moonlight silhouettes the clouds, creating a bright halo around the celestial body. Thanks to this silvery light, we can also see a slight swell on the sea surface. A few stars visible in the patches of clear sky between the clouds complete this impeccably executed atmospheric seascape.

Landscape with a Sunset

One of the main challenges of painting is capturing atmospheres where everything is steeped in an enveloping light. Atmospheric light changes over the course of the day and depending on the amount of cloud cover, the type of clouds and their position with respect to the sun or moon (the light source), the different elements of the landscape and the observer.

The Dutch painter Aelbert Jacobsz. Cuyp (1620–1691) addressed numerous themes throughout his career, but it was his landscapes bathed in warm dusk light that earned him the greatest recognition and fame. He painted them repeatedly, combining keen observation with an outstanding painting technique. At sunset, the landscape has a special glow.

Photographers refer to this time of day as the ‘golden hour’ due to the type of light that enlivens objects just before and after sunset. Cuyp masterfully captured it in his works, and this Landscape with a Sunset is a good example. The sun is located outside the scene, to the left, and it is easy to deduce from details such as its glare on the river surface and the long shadow cast behind the cowherd that it has not yet set. The light is impeccably handled.

The pinkish tones of the sky on the left have also been applied to the background mountains, still illuminated by the sunlight. The brighter part on the left contrasts with the duller area on the right, where the artist has included some grey cumulus clouds. The presence of a few gaps between them and their ragged contours suggest that they are remnants of storm clouds. The precision with which Cuyp has portrayed all these details, coupled with his painstaking rendering of the vegetation, attests to the artist’s skill.

Stormy Sea with Sailing Vessels

The drama of stormy weather, with its very choppy seas and menacing clouds, is a recurring motif in painting. The Dutch have always been accustomed to rough storms at sea that batter their coasts when powerful tempests sweep across the North Sea.

Blustering winds whip up the sea into large, frothy waves. Navigation becomes difficult under such conditions, and the risk of capsizing is high.

These striking weather events did not go unnoticed to Dutch painters, including Jacob Isaacksz. van Ruisdael (1628–1682), even if they deliberately chose such themes over others that were less arresting. The 1600s witnessed very rough weather in the North Atlantic, with long periods of relentless storms. Although seascapes are not the most common subject in this great landscape painter’s output, he produced a few notable examples.

One is precisely this Stormy Sea with Sailing Vessels, a highly dramatic depiction of a storm-lashed sea beneath a sky swollen with heavy black clouds (vertically rising cumulus clouds) that slant rightwards – like the boats’ sails – due to the effect of the strong wind. The influence exerted on Ruisdael by both Jan Porcellis (1584–1632), a specialist in seascapes, and Hendrick Martensz. Sorgh (c. 1610–1670) is evident in this work, which is compositionally very similar to Sorgh’s Sailing Vessels in a Strong Wind.

If we go by the Douglas scale, which officially classifies the state of the sea, its appearance in the painting suggests that it can be rated as ‘rough’, with waves between 2.5 and 4 metres high. According to the definition, in this state ‘large waves begin to form; there are many whitecaps and some spray. The sea surface looks agitated, with well-defined wave crests’.

Continues on the first floor

On the map you can see the rooms where the masterworks are located.

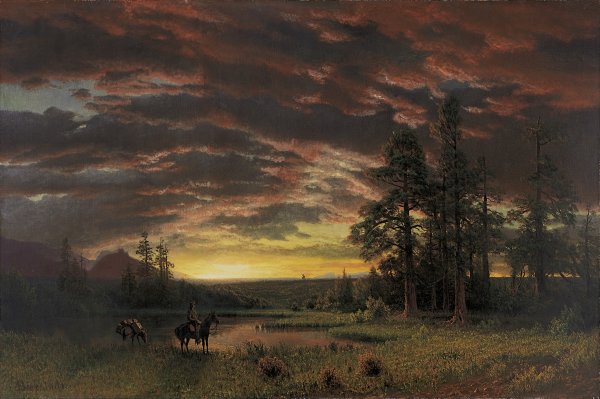

Evening on the Prairie

Nineteenth-century American paintings transport viewers to the unspoilt landscapes of the then still unexplored territories of the United States, which were often magnified and idealised. The painters of the Hudson River School focused their attention on the natural beauty of the majestic landscapes of the Wild West in what for them was an exciting visual exploration of places that were beginning to be discovered and colonised by ‘white men’.

One of the leading members of this group of painters was Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902). A German-born artist based in New Bedford, Massachusetts, he first came into contact with the unexplored lands of the American West in 1859 while taking part in an expedition to open up a new railway route to the Pacific. Over the course of several later trips he became captivated by the majesty of the places he discovered, which was often enhanced by the changing skies and atmospheric conditions.

Apart from large, sharp-peaked mountains, Bierstadt’s landscapes often feature stormy weather, with clouds covering much of the sky and intense glows of sunlight. Evening on the Prairie is a good example. The last rays of daylight illuminate a layer of stratocumulus clouds from below. A striking cone-shaped shadow is cast upwards by the sun, which has just set on the horizon, where the light is most intense. We find similar fiery skies in Twilight in the Wilderness by Frederic E. Church (1826–1900), another prominent member of the Hudson River School.

These and other compelling landscapes, painted in a deliberately eye-catching manner as advertising attractions, had a profound impact on American society at the time. Thanks to them, the idyllic natural environments of North America became widely known, helping reinforce a sense of national identity among the population.

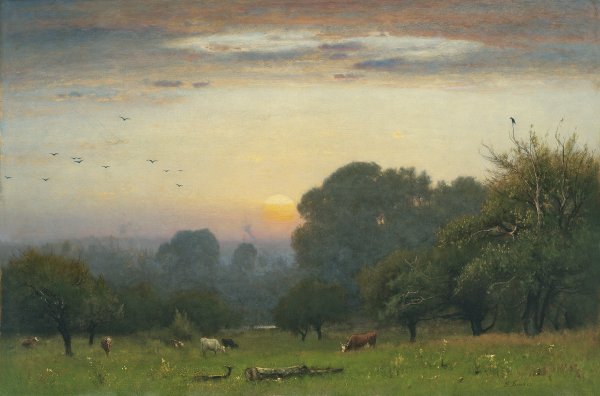

Morning

One of the most important nineteenth-century American landscape painters was George Inness (1825–1894). He was influenced by European landscapists such as John Constable (1776–1837), the French artists of the Barbizon School – who strove to glorify scenes of nature – and the English-born American artist Thomas Cole (1801–1848), a founder of the Hudson River School.

In Morning, Inness succeeds in conveying the impressions experienced in the open countryside at sunrise, such a special time of day. The work is so perfectly executed that we can almost sense the morning chill, the dew characteristic of the early hours when the temperature is usually at its lowest. The painting also conveys the calmness that prevails at that time of day. It is worth stopping to examine the details that the artist has included in this morning sky.

The upper part displays altostratus clouds, a type which are located between 2,000 and 7,000 metres above sea level and spread horizontally, forming a layer that covers large areas of the sky. They are fairly uniform in appearance, although they are commonly fibrous or striated, like those painted by Innes. Altostratus clouds are not particularly eye-catching except at sunset and sunrise (as is the case here), when the sun’s rays illuminate them from below and give them a plasticity they lack during the rest of the day. The presence of the mist in the lower part of the sky is revealed by its blurred appearance and more faded colours.

It is common at the beginning of the day: as the air cools during the night, near the ground it becomes laden with moisture, which is conducive to the formation of mist. George Inness recreates this natural scene so well that he practically transports us there, causing us to experience some of the emotions evoked by dawn. It is a vivid landscape, despite the artist’s deliberate idealisation.

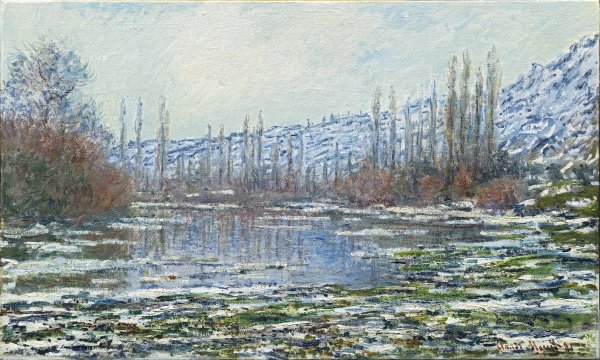

The Thaw at Vétheuil

The winter of 1879–80 was exceptionally cold in France and other European countries, then in the last throes of the Little Ice Age. The stretch of the River Seine that flowed through Vétheuil, 60 kilometres north of Paris, froze over completely.

The Impressionist painter Claude Monet (1840–1926) was living in this small French town at the time and produced a series of seventeen oil paintings showing the thawing of the river. The one in the museum, rich in nuances, transports viewer to the place. It expresses the silence – disturbed only by the murmur of the water and the cracking ice – the stillness of the trees and the coldness of the setting, conveyed in the painting by shades of grey and pale blue.

To have succeeded in creating a composition that conveys the spring thaw so effectively using loose brushwork – playing with different types of strokes and textures –is quite an accomplishment.

It was the desire to capture the unique and fleeting moments that nature offers us, particularly the changing forms of water and the skies, that led the Impressionists to break all the rules and revolutionise the world of painting. Throughout his life Monet repeatedly witnessed the Seine frozen over and the sequence of thawing. Sometimes he saw large blocks of ice being carried along the river, which he immortalised in other paintings.

He first depicted them in Ice Floes on the Seine at Bougival (1868) after experiencing another freezing-cold winter, that of 1867–68. When the artist moved to Giverny in 1890, not far from the river, he again witnessed this wondrous sight and recorded it in a series of twelve paintings.

In all of them he avoided excessive drama (drifting ice floes sweep everything away when they reach the banks), focusing instead on the serenity with which this natural process unfolds.

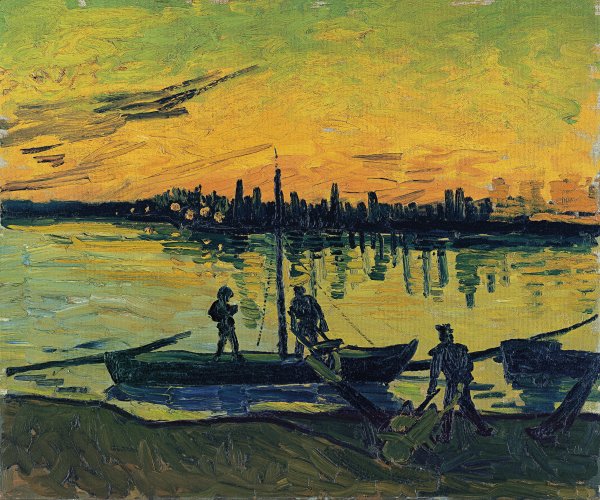

The Stevedores in Arles

The intense twilight colours in this painting are most likely related to the changes inflicted on the skies of Europe – and other parts of the world – by one of the most violent volcanic eruptions the Earth has witnessed since the beginning of humanity.

On the night of 26 August 1883 the small island of Krakatoa, located in the Sunda Strait between Sumatra and Java in Indonesia, literally exploded. The eruption released a huge number of particles into the atmosphere, the smallest of which reached an altitude of 80 kilometres.

Strong winds in the upper atmosphere gradually dispersed these aerosols, forming a veil that covered much of the planet. This mantle of tiny particles caused a five-year global cooling, disrupting weather patterns. During this ‘volcanic winter’ the presence of these elements in the atmosphere darkened the sky and heightened the intensity of the yellows, reds and oranges seen during sunrises and sunsets.

This sight continued to be enjoyed for several years both in Europe and elsewhere in the world and did not go unnoticed to artists such as Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890), who painted this picture. In February 1888 he arrived in the French town of Arles, on the Côte d’Azur, in search of Mediterranean light and found it to be enhanced by the dispersed volcanic haze that still filled the skies. The Stevedores in Arles shows a blazing dusk sky, as the action takes place shortly after sunset.

Its warm, enveloping glow is reflected in the waters of the Rhône, on one of whose banks, in the foreground, the stevedores are positioned, silhouetted against the light. Van Gogh witnessed the scene with that fiery sky firsthand, as he described it to his brother Theo in a letter written early that August. However, it is possible that the artist’s main reason for painting these striking colours was to experiment with his palette.

Summer Clouds

This arresting painting, executed in thick brushstrokes, transports viewers to the South Seas. Its maker, the German painter Emil Nolde (1867–1956), was fascinated by the clouds and the choppy turquoise sea he observed in 1913 while travelling around the former German possessions in the Pacific.

He stated that, ‘Very often, while lost in thought, I would gaze out of my window at the sea for a long time. There was nothing there but water and sky’.

Unlike other painters, who set out to portray cloud formations and the sea surface realistically, Emil Nolde focused on the sensations aroused in him by the different elements of nature he observed. In Expressionism– of which Nolde was a foremost practitioner – reality is distorted, as the priority of the artists belonging to this movement was to express their feelings in their works.

The change of scenery – from cold, cloudy Germany to the torrid, sunny tropical region – must have made quite an impact on the artist. The intense heating of the air near the ground in the tropics is conducive to the formation of large cumulus clouds, which have a puffy appearance and are very white at the top, some culminating in cumulonimbus (storm clouds). There are several cumulus clouds in Summer Clouds, but they are part of a scene that would be impossible in real life, as they are located above the surface of the sea, where there is hardly any convection (rising warm air), as opposed to over land.

If you ever sail through Polynesia, you will find that cumulus clouds only form over islets and atolls, as that is the only place where strong rising air currents occur. It can be deduced from this detail that Emil Nolde did not paint these clouds straight from life, viewed through his window, but included them in the picture after repeatedly contemplating them during his trip.

Continues on the ground floor

On the map you can see the rooms where the masterworks are located.

Thunderstorm off the Coast

No skies are more dramatic than stormy ones, nor is there a more expressive way to represent the unleashing of the forces of nature than to paint what we commonly identify as a storm or tempest, even though technically they are not the same thing.

Storms inspire a curious mixture of fear and fascination, and it is therefore no wonder that they are a recurring motif in landscape painting.

We have already seen a few on this tour. Painters usually incorporate them into their works to capture viewers’ attention, and the Dutch painter Simon de Vlieger (1601–1653) certainly succeeds in doing so in this impeccably executed seascape. One of the most eye-catching features of this painting is the thunder and lightning triggered by the storm.

These phenomena are not depicted in most storm scenes, especially if they are large paintings, though a few painters have risen to the challenge throughout history. The difficulty lies both in the extreme fleetingness of the electrical discharge and in the spectacular atmospheric light caused by the flash. Thunderstorm off the Coast features orange-coloured lightning bolts with their characteristic zigzag shapes.

The darkness of the storm cloud on the left is very skilfully portrayed. The dark parts of the sky contrast with the light emerging from the horizon and illuminating the choppy sea surface. The storm poses a threat to the boats in the scene. The crew of the one in the foreground have nearly finished lowering the sails and have dropped anchor to prevent it being swept along by the violent gusts of wind.

De Vlieger’s rendering of the large dome-shaped cumulonimbus clouds that are causing the stormy weather is highly realistic. The upper part of the boat in the background, on the right, has a whitish appearance as it is illuminated by the sun.

The Marshes at Rhode Island

The prolific Martin Johnson Heade (1819–1904) was one of the leading nineteenth-century American landscape painters. This exceptional painting depicting one of the most recurrent themes in his work – the brackish marshes in the eastern regions of the United States – attests to his talent.

The constant changes in light that take place in these marshes, especially when the sun is close to the horizon – either at dawn or dusk – caught the artist’s attention, and he captured them masterfully in some of his paintings. The best known and most famous are his depictions of the landscapes of the New England marshes, with their perfect handling of light and shadow and alluring skies.

In the Marshes at Rhode Island, everything is shrouded in a twilight haze. It is not easy to tell whether the scene represents the moment before dawn or after sunset as crepuscular light is similar in both cases. However, other comparable landscapes by the artist and the cumuliform clouds shown here, silhouetted against the background horizon, suggest that it is an evening twilight.

Although these clouds can form at any time of day, they most commonly appear after midday, reaching their peak size in the evening. As the ground grows warmer the vertical air currents generated above it trigger convection, which is the mechanism responsible for the vertical formation of cumulus clouds. Another interesting detail is the vivid colour of the lower part of the small clouds that dot the sky.

This is due to the light shining directly from the sun, which is hidden below the horizon. Such realistic representations are only achieved by painters who are keen observers of the sky, and Martin Johnson Heade was one of them.

Étretat. The Cliff of Aval

The landscapist Eugène Boudin (1824–1898), one of the first French artists to paint outdoors, depicted the sea in many of his works, most likely influenced by his Norman background.

This picture is a good example, although its atmospheric elements are more interesting than the sea itself. The sky fills the upper two-thirds of the canvas, except for the portion on the left where the distinctive promontory is.

The French town of Étretat in Normandy is famous for its cliffs, particularly the one shown here: the Aval cliff, popularly known as the ‘eye of the needle’. In early autumn 1890, after spending the summer in his native region, Eugène Boudin painted at Étretat for several days. He was not alone in his attraction to this spot, as it was also popular with Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), Gustave Coubert (1819–1877) and Claude Monet (1840–1926), among other great artists. A flotilla of fishing sailboats plies the waters. The sea is somewhat choppy due to the wind.

The majestic atmosphere above it stands out on its own. The clouds dotting the sky are mostly the fair-weather cumulus type, though a few are somewhat larger. The loose dabs of white that blur the patches of blue sky represent high clouds that may possibly herald a change in the weather – a common occurrence in late September in Normandy.

It may be deduced from a small detail in the painting that atmospheric stability prevailed and that it was a windy day: a tiny steamship travelling along the horizon, leaving behind a trail of smoke that is perfectly parallel to its path. If the atmosphere had been unstable, the plume would be more dispersed and more vertical. The combination of changing forms in the water – the sea surface in this case – and the atmosphere appealed irresistibly to the Impressionists.

Route de Versailles, Louveciennes, Winter Sun and Snow

Snowfalls, particularly their ability to transform the landscape and their own metamorphoses, attracted the attention of Impressionist painters such as Claude Monet (1840–1926) and Camille Pissarro (1830–1903).

In 1869 Pissarro and his family settled in Louveciennes, a village on the outskirts of Paris. The house-studio where he lived was located on the way from the village to Versailles, and he chose the view from this road as the subject of a series of twenty-two canvases painted at different times of the year and focusing on the effects of light and seasonal changes on the local landscape.

He produced these pictures between 1869 and 1872. At the end of October 1869 autumn prematurely tinged France white. The intense cold and snow arrived earlier than usual. It was the prelude to a particularly harsh winter in France and other European countries, which witnessed several cold spells. Camille Pissarro experienced these winter storms firsthand, recording them in several of the paintings in the series.

The first snowfall he painted was almost certainly that of October 1869, which Monet also depicted from the other side of the road. Monet was then living in the nearby town of Bougival and stayed with Pissarro and his family for a time. An interesting rivalry subsequently developed between the two artists, with the road as the natural setting for their painting studies.

Pissarro probably painted Route de Versailles, Louveciennes, Winter Sun and Snow in January 1870 after the northern half of France was hit by a heavy storm. The picture shows how the blanket of snow has melted after several days. The road appears to be almost completely clear of snow except for the remains that have accumulated on either side of the road and in adjacent areas, mainly in the shade.

The Flood at Port-Marly

Skies, river landscapes and reflections on the water were some of the motifs that most interested the Impressionist painter Alfred Sisley (1839–1899).

From 1874 to 1877 he lived in the French town of Marly-le-Roi outside Paris. The town was located next to Port-Marly by the River Seine, where he witnessed heavy flooding in March 1876.

He had already experienced a similar phenomenon a few years earlier, in December 1872, when he went to Port Marly to paint a series of four works illustrating different stages of that flood. He chose to portray the same subject again, producing a series of seven paintings, all beautifully executed and far removed from the drama usually associated with natural disasters. These paintings chart the whole sequence of the flood, from the moment the streets of Port-Marly are submerged in water and its inhabitants are forced to abandon their homes in boats to the stage when the entire village becomes swamped in mud.

It is precisely the latter situation that Sisley depicts in this last painting in the series. The street alongside the watercourse is covered in mud, and large puddles are still visible. The waters of the Seine have now receded and life in Port-Marly is gradually returning to normal. The painter takes pleasure in the rendering of the sky, where he includes some medium-sized cumulus clouds (the mediocris kind); the reflection of the sky in the puddles is a further demonstration of his skilled brushwork.

Alfred Sisley spent several days in Port-Marly painting the series of canvases from life, choosing different locations and immortalising the sequence of events. His series provides a detailed pictorial chronicle of a hydrometeorological episode, an accomplishment significant in its own right.

The works are also highly appealing, due in part to the puffy clouds that the artist must have seen in the skies above Port-Marly during those days, though he undoubtedly enhanced them for aesthetic purposes.

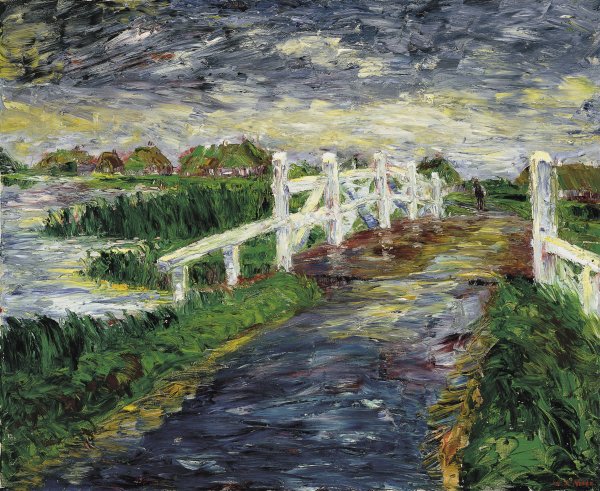

Marsh Bridge

The meteorological tour of the museum ends by stepping across this Marsh Bridge painted by Emil Nolde (1867–1956) in 1910, three years before he departed for the South Seas where, among other works, he produced Summer Clouds, also included in this trail.

Both canvases display vivid colours – a common feature in the artist’s work, which he used to convey his experiences and the feelings and emotions aroused by certain situations in the places he visited.

Nolde was an Expressionist and the scenes depicted in his paintings are not realistic but distorted. The painter spent the summers of 1909 and 1910 in the environs of Ruttebüll (Rudbøl in Danish), a town on the border between Germany and Denmark. It is a marshy region, full of wetlands, as is evident from this work.

Nolde invites us to follow the path opening up in front of us in the foreground and to cross the bridge. The bluish tones in the section of path in the lower part of the canvas suggest that it is flooded. The dark storm cloud in the upper part of the sky, interspersed with random dashes of light colours that break the uniformity of this cloud layer, is reflected in it. A typical summer’s day in northern Europe is very different from one in the south.

In the northernmost part of the Frisia region, where Emil Nolde spent those two summers, cool, rainy and cloudy days and unpleasant weather prevail as opposed to the heat and sunshine of the Mediterranean. The scene depicts a moment, most likely fleeting, when the rain has stopped but the wind is blowing, as indicated by the slanting green reeds on either side of the bridge.

The light emerging on the horizon enlivens the landscape and intensifies the colours. We can perceive the intense sensations which must have overcome the artist, conveyed through his expressive style of painting characterised by colour and loose, energetic brushstrokes. As Nolde stated, ‘Nature in art represents the most vigorous, vital, and blooming power of nature’.