Art has never been silent. Artists have always spoken out against any form of injustice, against inequality, against discrimination... and, of course, against the global problem of climate change. Art and Climate Change is a special tour that highlights the role art has played in response to the alterations in nature caused by human actions. The itinerary draws connections between pictures in the Thyssen-Bornemisza collections and the work of artist and filmmaker John Akomfrah, specifically his video installation Purple, on view in the galleries of the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza in spring 2018. The featured works were chosen not only for their formal affinity with certain stills from the film, but also because, like Purple, they recall, illustrate and/or stimulate reflection on the destruction of the environment.

Tour artworks

Paul Gauguin

Mata Mua (In Olden Times)

Room F

In 1891, Paul Gauguin travelled to Tahiti looking for fresh artistic inspiration far from Western civilisation. His goal was to learn about the ancient Maohi culture, threatened by colonisation and Christian evangelism. Gauguin believed that immersing himself in the innocence of those native peoples would revitalise his art, which he felt was conditioned by what he had seen and learned in this hemisphere. However, what he found were vestiges of a glorious past already on the verge of extinction, as the Polynesian islands had just lost their independence and become a French protectorate. Mata Mua (In Olden Times) is an ode to that native lifestyle the painter yearned to experience. What we see in the picture in the Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection is a recreation of the Tahiti of Gauguin’s dreams, where several women play the flute while another dances before a stone sculpture of the moon goddess Hina. The entire composition is constructed of flat colour fields. A large tree trunk divides the space into two areas: music occupies the foreground and dance the middle ground. The scene is set against a backdrop of pink and purple mountains. Through his paintings, Gauguin hoped to bring back those sacred “olden times” when humans lived in harmony with nature and rediscover, far from Europe, the primitive deities and paradise on earth. Soon after settling in Tahiti, he set off on a tour of the island to search for places as yet untainted by the rampant corruption and decadence in Papeete. Purple is a wake-up call, in which the artist reminds us of all the beauty we stand to lose. Like Gauguin, Akomfrah set off on a long journey that gave him the chance to film in ten different countries, identifying landscapes doomed to disappear, from Greenland and Alaska to volcanic islands in the South Pacific and various locations across the United Kingdom.

Drawing on archive footage, spoken word and music alongside often epic shots of contemporary landscapes that have been altered by global warming and rising temperatures, Purple forsakes a linear narrative in favour of an almost overwhelming montage of imagery and sound. Purple posits myriad ideas, but they all revolve around the fact that progress can cause profound suffering. In the still that dialogues with Mata Mua, Akomfrah has arranged the composition in a manner similar to Gauguin: the image is split down the middle by the trunk of a banyan tree whose crown, as in Mata Mua, is outside the frame, offering only a glimpse of the lower branches. There is another link between these two images, for Akomfrah shot his scene on Nuku Hiva, an island in the Marquesas archipelago very close to Hiva Oa, the island where Gauguin died.

John Akomfra's image mentioned come from the footage of Purple videoinstallation and is available at the downloadable guide in pdf.

Emil Nolde

Summer Clouds

Room 34

In 1913, Germany’s imperial colonial office invited german artist Emil Nolde to join an anthropological expedition to the South Pacific islands. The mission of that expedition, led by Külz and Leber, was to study the health of the New Guinean population. On his travels through Russia, Siberia and Manchuria, the painter made numerous sketches and several paintings of those exotic, faraway cultures. For barely two years (1906-1907), Nolde had been a member of Die Brücke [The Bridge], a group founded in Dresden in 1905 by fellow artists Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. Die Brücke members wanted their art to build a bridge to the future, to new ways of painting and expressing feelings. In pursuit of these goals, they sought inspiration in the manifestations of other cultures, such as those displayed in Dresden’s ethnographic museum. To experience that idea of Eden, of paradises lost, they retreated from society and spent long periods in remote corners of nature in northern Germany.

Summer Clouds, a work acquired by Baron Hans-Heinrich Thyssen in 1972, was painted by Nolde the same year as his trip to the southern hemisphere. For Nolde, an artist who spent his life on the shores of the Baltic, the sea was a constant source of inspiration. The changing moods of that sea held strong symbolic significance for him.

The clouds in the still from Purple, like Nolde’s, are driven by a strong wind. We are still on Nuka Hiva. Nolde was one of several artists invited to participate in those early multidisciplinary expeditions organised by certain European governments, and John Akomfrah received a similar invitation from TBA21–Academy. Founded by Francesca von Habsburg in 2011, and drawing on her experience as a producer of cross-disciplinary art installations and socially engaged cultural programming, the academy brings together artists, scientists and thought leaders on collaborative expeditions. TBA21–Academy is guided by its mission to foster a deeper understanding of the ocean through art and a belief in the power of exchange between disciplines to generate creative solutions to the ocean’s most pressing problems. Chus Martínez, curator of the project, will plan three expeditions in the second cycle of The Current, a three-year fieldwork programme for artists, cultural agents and scientists also promoted by TBA21–Academy. The aim is to highlight the crucial role of artistic intelligence in comprehending the radical truth about our climate, and to help us establish an emotional and cognitive bond with the ocean and everything that dwells in it.

John Akomfra's image mentioned come from the footage of Purple videoinstallation and is available at the downloadable guide in pdf.

Emil Nolde

Red Clouds

Room 34

Since the dawn of humanity, people have always had an innate desire to play a leading role in the world, to be its uncontested sovereigns. Although the intensity of that urge has varied throughout history, there is no doubt that this human ambition has never been as blatant as it is today. Humans of the 21st century feel that, from their position of superiority, they can rule and control all that surrounds them. Nature is one of the realities that humankind strives to bend to its will, without respecting or observing its rules and rhythms. In contrast to this relationship with nature, based on domination and exploitation, German Romanticism invited people to adopt a more contemplative attitude towards the natural world.

The solitary figures Akomfrah inserts in many of the scenes in Purple are seen from behind, like the protagonists in the pictures of Caspar David Friedrich, the greatest exponent of German Romantic painting. This device was used by both artists to engage viewers. Without being asked, they are pulled into the scene. The settings, anything but ordinary, recreate the immense grandeur of nature, before which that human figure becomes tiny and insignificant. With these impressive panoramas, Akomfrah conveys the feeling of emptiness we experience when contemplating some of the majestic sights now lost to us. Are they lost forever?

Akomfrah explains his own position in the work: “In a very real way, I’m present in the film. I’m the figure in the brown shirt who gets rained on. [...] It sounds a bit mystical, but for me everything starts with place. Wherever we filmed, it began with me asking the landscape the same question: ‘What can you tell me about the nature of climate change?’ As an artist and filmmaker, I’m dependent on the responses I get from the environment.”

The British artist rounded out his inspirations for Purple with a varied array of literary texts and poems. One of the selected poems is “El Desdichado” [The Wretch] by Gérard de Nerval, a French poet whose choice of theme and manner of presentation also denote a strong Romantic influence. Other literary sources which the artist has mentioned as seeds of his film are discussed later in the tour.

John Akomfra's image mentioned come from the footage of Purple videoinstallation and is available at the downloadable guide in pdf.

George Catlin

The Falls of Saint Anthony

Room 31

George Catlin’s work the falls of saint anthony transports us to the distant territory of the American West before it was tainted by civilisation. Between 1830 and 1836, the painter retraced the itinerary of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark’s legendary expedition along the Mississippi, becoming the first artist to explore the Far West. However, Catlin was not the only 19th-century artist to produce genre paintings featuring Native Americans. The picture in the Thyssen Collection depicts a scene in which two traditionally attired American Indians, carrying fish caught in the great river, cross a meadow very close to the Falls of Saint Anthony, already a famous landmark at the time. The falls had been discovered around 1680, and the place was held sacred by the Dakota tribe who lived in the vicinity. When the artist was commissioned to paint the falls again in 1871, he produced a replica of the work made several decades earlier. The scene is a complete fabrication, for by that time part of the pristine wilderness had already been destroyed. To emphasise the vastness of the place, the painter used a distant perspective that allowed him to offer a broad panoramic view, a device Akomfrah also employs in Purple.

Unfortunately, Akomfrah’s still is not a fabrication. In it we see a completely devastated ecosystem. What should be a dense evergreen forest, like the one beside Catlin’s meadow, has been brutally razed and littered with plastic detritus, a foe to any ecosystem, making its eventual recovery doubtful at best. There is no sign of the species that once lived here; they were probably exterminated like the millions of bison that roamed the prairies in pictures painted by Catlin and his colleagues. Akomfrah’s still is a replay of the tragedy that befell the Falls of Saint Anthony: another stunning natural landscape sacrificed to industry’s insatiable appetite.

The encyclopaedia defines ecology as the branch of science that studies and analyses interactions between living beings and their environment, understood as the combination of abiotic factors (such as climate and geology) and biotic factors (organisms that share the habitat). Purple talks about how certain objects (organic and inorganic assemblages) interact with others in the fragile ecology of things of modern-day life. At this point, this tour intersects with the focus of another thematic tour of the Thyssen-Bornemisza collections, which we also invite you to explore: Sustainability: Social Challenges Illustrated in the Collection, available here.

John Akomfra's image mentioned come from the footage of Purple videoinstallation and is available at the downloadable guide in pdf.

Georgia O'Keeffe

From the Plains II

Room 46

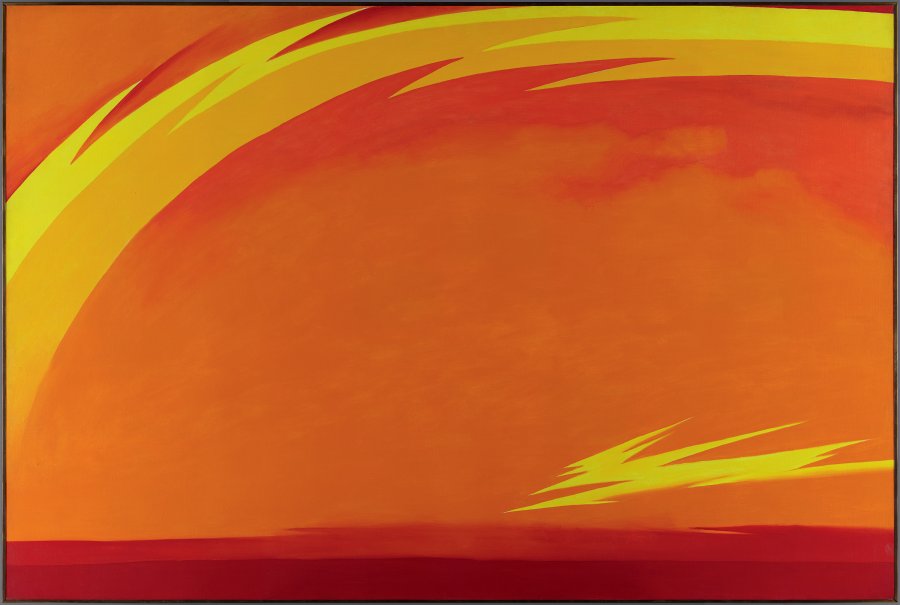

The next two works were paired because of their obvious formal similarity in the use of the same palette, arranged in large blocks of colour, and the same horizontal format. The still in this case is from Vertigo Sea, a documentary Akomfrah made in 2015 which can be interpreted as the prelude to Purple. The threescreen film Vertigo Sea is a sensual, poetic and cohesive meditation on man’s relationship with the sea and exploration of its role in the history of slavery, migration and conflict. Vertigo Sea pointed out the grave danger facing our oceans, and, as we have already seen, Purple expands on this theme to explore related problems: the importance of the information stored in glaciers (often called the “memory of ice”), the extinction of certain mammals and, of course, global warming. Georgia O’Keeffe’s work seemed well-suited to this topic given the impression of blistering heat it conveys. From the Plains II (1954) is the second version of a painting made 35 years earlier in Amarillo, Texas. In that original, vertical work, O’Keeffe had attempted to capture, according to her own testimony, the fascination she felt upon witnessing huge herds of cattle being driven across the great plains in that arid country, raising an enormous cloud of dust and a deafening racket. In this later version, the vastness of the Texas plains is even more breathtaking, accentuated by the horizontal canvas and the fiery colours of the setting sun. Starting in 1929, O’Keeffe’s obsession with the light that had so thrilled her in Texas led to prolonged absences from New York to enjoy sunny New Mexico, where she eventually settled in the small village of Abiquiú in 1949. In that remote location, the luminosity of her paintings became even more transparent, occasionally displaying a greater interest in indigenous culture or a degree of religious symbolism. At the same time, the formats of her canvases grew larger to accommodate the infinite scale of the desert landscape. This is precisely how we think of American painting, as the depiction of grand natural scenery with wide open plains spreading as far as the eye can see.

On the subject of global warming, Akomfrah says, “In a way, this is a person of colour’s response to the Anthropocene and climate change, which is not just a white, European fixation, though it is often presented that way. When I stand on a street in Accra, I can feel that it is a city that is literally at boiling point. It is way hotter than it was in the 1960s or even the 1980s. We need to start looking at climate change in radically different ways, not just as part of a Western-based development narrative. It’s a pan-African concern of great urgency, but how long it will take people to see it as such is a whole other problem.”

At this point in the history of human evolution, we should all have a highly developed ecological conscience, but we know this is not the case. We must have it on some level, because we see it in the rest of the earth’s animal species, but it seems to be dormant in many individuals. Can it be awakened by works like Purple? The choice is ours: we can live according to the dictates of that conscience, or let it relapse into comfortable numbness. Heeding our ecological conscience may complicate our lives, but it ensures that future generations will be able to enjoy theirs.

John Akomfra's image mentioned come from the footage of Purple videoinstallation and is available at the downloadable guide in pdf.

Claude Monet

The Thaw at Vétheuil

Room 33

Anthropocene is a term coined by scientists for the geological age in which we are now living, a period defined by the influence of human activity on climate and the environment. The installation Purple is a response to the Anthropocene concept. In 1989, Akomfrah had what he calls “a major turning point”, when he travelled to Alaska to make a documentary for the BBC about the Exxon Valdez oil spill and its disastrous impact on the Alaskan ecosystem. “The destruction of the livelihoods of the Inuit community immediately resounded with me because it recalled the worst excesses of colonial exploitation. It felt like I was in a post-colonial space that was very much haunted by the past.” Another major source of inspiration for Purple is a book called Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology After the End of the World (2013). Written by Timothy Morton, an English academic, it posits the idea that global warming is the most dramatic illustration of a “hyperobject”—an entity of such vast temporal and spatial dimensions that it baffles our traditional ways of thinking about it and, by extension, doing something about it.

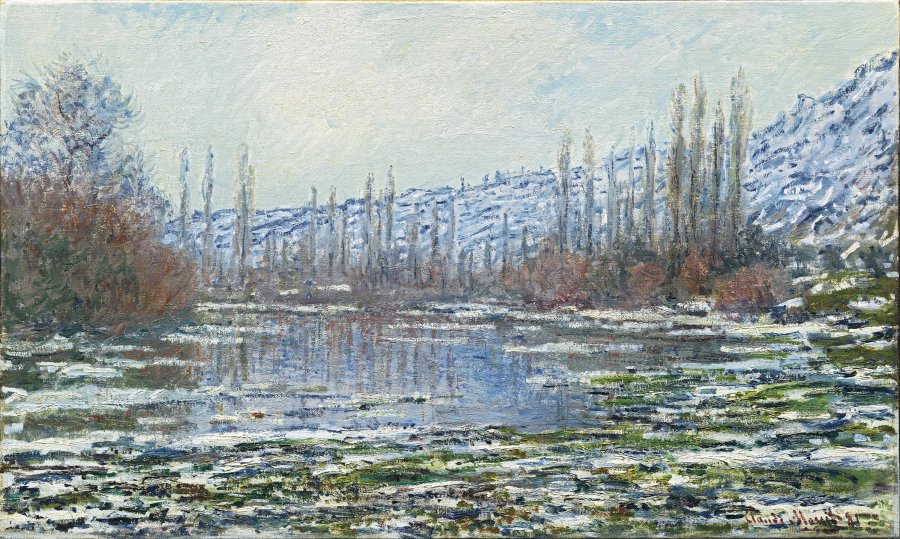

With its carefully balanced composition, this still from Purple perfectly captures the stillness, silence and serenity conveyed by that landscape.

The Thaw at Vétheuil, a work in the Thyssen collections, is one of seventeen oils in which Monet portrayed the ice breaking up on the Seine after an intense freeze in the winter of 1879. According to period accounts, that winter was so cold that Paris and its environs were virtually paralysed by the constant snowfalls and heavy ice brought on by abnormally low temperatures. At the time Monet lived in Vétheuil, a village on the banks of the Seine north of the French capital, and there he watched as the flowing river came to halt and froze over. Monet was always intensely interested in depicting the ephemeral, changing nature of water, and the circumstances of that winter allowed him to capture the moment when, as the temperatures rose, the ice broke into chunks that were carried downriver. The elongated format of the canvas, similar to Akomfrah’s screens, underscores the composition’s emphatic horizontality, broken only by the vertical lines of the trees and their watery reflections. With a few rapid, loose brushstrokes and a very limited palette, Monet made the most of the sparsely populated scene and managed to convey a sense of abandonment and melancholy. One of themes in which Akomfrah displays a keen interest is the “memory of ice”.

Our daily lives are flooded with reports about what Chus Martínez calls “the fury unleashed” by the imbalance in nature we have caused, making abnormally mild winters and dramatically dry, hot summers increasingly common.

John Akomfra's image mentioned come from the footage of Purple videoinstallation and is available at the downloadable guide in pdf.

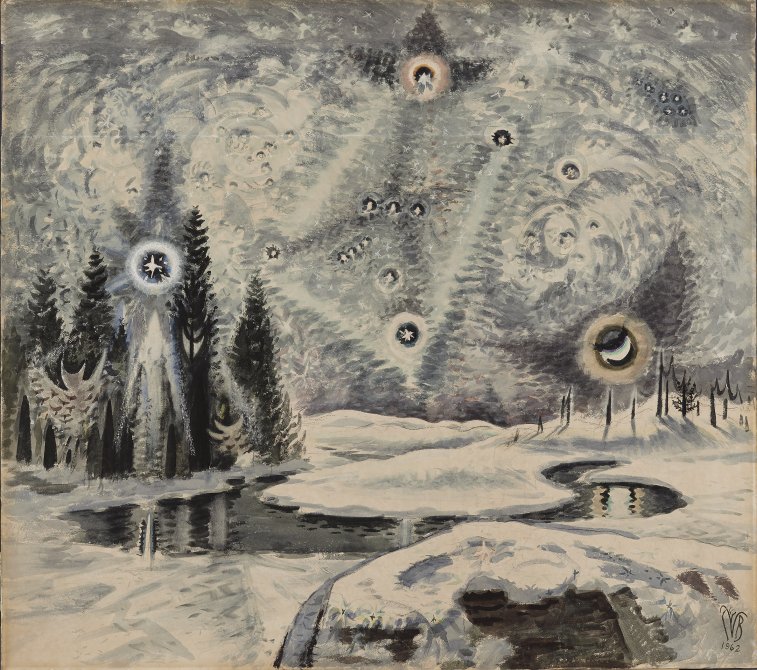

Charles Ephraim Burchfield

Orion in Winter

Room 46

On 17 November 1933, Charles Burchfield wrote in his diary, “the other night I lay awake, tortured by a multitude of thoughts; outside the sky was blanketed with soft strangely luminous clouds, in which now and then appeared ragged holes thru which glowed the deep indigo sky.” Burchfield had a good knowledge of astronomy and, as we can infer from both his writings and his paintings, was fascinated by the sky and the heavenly bodies: not only the sun and moon, but also the Pleiades and other constellations, particularly Orion, which appears in winter. The 1962 work Orion in Winter is a fantastic scene, an evocative night landscape where the moon and stars shine brightly in the darkness and illuminate the snowy white countryside. In 1962, Burchfield stated that it was based on the countless sketches he had made in 1917, his “golden year”, when he was experimenting with the visualisation of sounds. There is a dreamlike silence and stillness in Orion in Winter.

The Purple still chosen to dialogue with Orion in Winter also has a good or great deal of fantasy. Both artists present images which, rather than depicting recognisable locations on earth, seem to evoke otherworldly scenes. Circular and vertical elements organise the two compositions. Although it is suggested that humanity has reached the “end of the earth” and has no choice but to go beyond its confines, we must not concede defeat. The solution is in our hands.

John Akomfra's image mentioned come from the footage of Purple videoinstallation and is available at the downloadable guide in pdf.

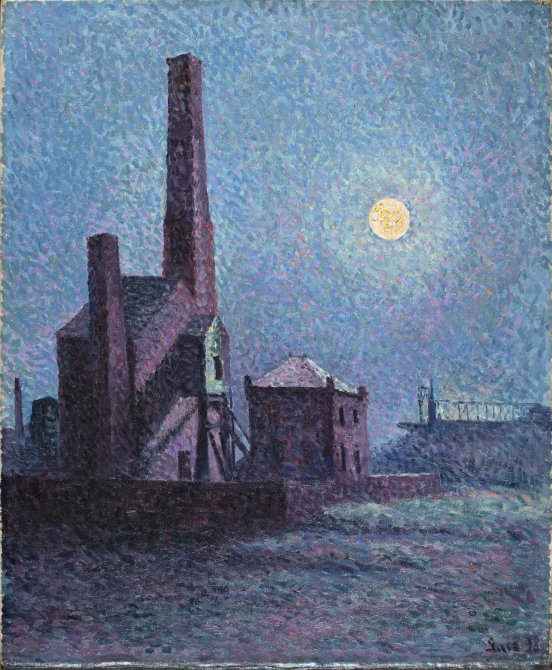

Maximilien Luce

Factory in the Moonlight

Room G

John Akomfrah grew up in the 1960s in the shadow of battersea power station in south London. As a child, he remembers “feeling as if I was enveloped in something whenever I played on the street. You could sense it in the air, you felt it and saw it, whatever was emanating from the huge chimneys. We were being poisoned as we played, but no one spoke about it. The conversations in the pub tended to be about football rather than carbon monoxide poisoning.”

This segment of the film focuses on the environmental problems derived from supplying energy to our cities, entities which have now become sprawling megalopolises. Many modern artists have expressed concern about industrialisation, a case in point being the 1898 work Factory in the Moonlight by Maximilien Luce, now in the Thyssen collection. Foundries, steel mills, blast furnaces and chimneys are settings frequently found in Luce’s oeuvre, depicting the labour of roller mill operators, welders and other workers. Luce was a Neo-Impressionist painter with direct ties to the Belgian group Les XX, with whom he exhibited in Brussels. He became close friends with the poet Émile Verhaeren and the painter Theo van Rysselberghe, who on several occasions urged him to visit the heavily industrialised area of Charleroi. Luce had a strong sympathy for workers and depicted them toiling in extremely harsh conditions. In other works, that industry-littered landscape is rendered as a still life, devoid of figures. Many are nocturnal scenes illuminated only by the soft light of the moon, which allowed Luce to explore and exploit Neo-Impressionist discoveries about the use of light and colour. In Factory in the Moonlight we find a wide range of purple and violet hues. Another work on a similar theme is Waterloo Bridge, painted in 1906 by André Derain, who depicted a London already suffering from the effects of industrialisation. This work is discussed at length in the tour Sustainability: Social Challenges Illustrated in the Collection, available here.

There is another point of comparison between Luce’s painting and Purple: Akomfrah, speaking of his piece, has mentioned that he wanted to achieve the same effect as pointillist painting. He explains how he intertwined each of these large, multiple visions so that, “like a Seurat painting”, they can be read, from an appropriate distance, as a whole.

John Akomfra's image mentioned come from the footage of Purple videoinstallation and is available at the downloadable guide in pdf.

Milton Avery

Canadian Cove

Not on display

At this point in the film, Akomfrah introduces the theme of “What the sea gives back to us”. The oceans, rivers and lakes that provide us with so many boons “regurgitate” the worst of our societies. In this still we see another solitary figure, sitting on something suggestive of a vehicle, although only the tyres are afloat. The message is clear: we have turned our marine environments into rubbish tips. Is that person facing the problem? Are we facing that dramatic reality or avoiding it?

A more hopeful perspective can be found in our collections in the work of Milton Avery, a painter who defies classification. Although he lived in New York from 1925 onwards, his pictorial universe was always far removed from the tensions of city life and close to peaceful tranquillity of nature. Canadian Cove exemplifies the painter’s delicate style and presents a pleasant, Arcadian world. The quiet coastal scene recalls the summer that the Avery family spent on the Gaspé Peninsula near Quebec in 1938. His wife Sally and their daughter March are portrayed reading or drawing peacefully on a promontory overlooking the cove. His use of broad, flat colour fields has led some to call him the Matisse of North America. Mauves and purples feature prominently in his palette.

When discussing Purple, Akomfrah does not conceal the fact that his artistic sensibility is what drives him to face the problem of climate change and share his perspective with the world, hoping to stir consciences but knowing that the degree of commitment to the cause will vary for each individual. Avoiding the conventional alarmist aesthetics of eco-documentaries, Purple is a beautiful invitation to reflect on all these matters.

John Akomfra's image mentioned come from the footage of Purple videoinstallation and is available at the downloadable guide in pdf.

Mark Rothko

Untitled (Green on Maroon)

Room 47

American artist Mark Rothko believed that colour was the best means of expressing emotions. The vibrant colours of his mature work, applied in successive, heavily diluted coats of glaze, envelop and transport viewers to a spatiality beyond measure. To heighten the introspective, hermetic quality of his works, a range of purples, greys, dark greens and browns came to dominate his palette, as illustrated by Untitled (Green on Maroon) in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection. That practice resulted in pieces that invite contemplation and meditation, which explains why his paintings have been associated with northern European Romanticism. When the MoMA organised a solo exhibition for him in 1961, Rothko closely supervised the installation of his works, placing the paintings quite close together and insisting on very dim lighting to enhance their intensity and drama. That exhibition design has been interpreted as a reflection of the artist’s depressed state of mind at the time.

The title given to John Akomfrah’s latest work, Purple, is apparently quite simple. When discussing his choice of title, the artist has described purple as a wonderful colour because it is unnatural, as a hybrid resulting from the mixture of red and blue, and because he finds it ideal for representing opposing concepts, which is what his art is about. But his art is also about the vitality and volubility of things, the active powers of non-subjects and their impact on our future biosphere. The video installation is presented on six immersive big screens which Akomfrah has arranged very close together, as Rothko did with his large canvases, leaving only a small gap between each and extending them from floor to ceiling. The filmmaker also shares Rothko’s feelings about lighting. In Purple, the ambient light is dimmed as much as possible; spectators are bathed in the glow of the projected images, making them lose touch with reality to an extent. After passing through a narrow funnel-like corridor, visitors are confronted with the surprising image of a room painted and carpeted entirely in purple. This theatrical staging, accompanied by a continuous soundtrack synchronised with the images on the screens, achieves the effect of a total work of art.

Both Rothko’s and Akomfrah’s work demand time and engagement from the viewer.

John Akomfra's image mentioned come from the footage of Purple videoinstallation and is available at the downloadable guide in pdf.