A day in New York

By María Corral and Elisa Sopeña

"There is something in the New York air that makes sleep useless".

Simone de Beauvoir

This A Day in New York itinerary takes us through a selection of masterpieces at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza to the heart of this unique and unrepeatable city. A source of inspiration for painters, writers, photographers and film-makers, we shall stroll through its neighborhoods and museums, meet its characters and enjoy its history. This is an opportunity to turn travelers, and discover the throb and thrill of this fascinating city.

Starts on the ground floor

On the map you can see the rooms where the masterworks are located.

Tough Customers

John George Brown,the son of a ruined lawyer, arrived in New York from his native England in 1853, on the day of his twenty-second birthday. He first set himself up in Brooklyn, where he opened a portrait painter’s studio, and in 1861 moved to Richard Morris Hunt’s Tenth Street Studio Building, a workshop specifically created for artists, where he remained for the rest of his career. Brown was known as the artist “who has so successfully caught what one might call the elf-life of New York – that flickering phantasmal humanity of our streets and alleys.” As he stated to an early biographer, “I want people a hundred years from now to know how the children that I paint looked.” The painter, who grew up in poverty in England, remembered his impoverished childhood when he helped to support his mother, brothers and sisters.

After he had achieved economic success, Brown proudly acknowledged his beginnings as a working man, stating that he did not paint street urchins “solely because the public likes such pictures and pays me for them, but because I love the boys myself, for I, too, was once a poor lad like them.”

Some of these abandoned children,their faces “preternaturally aged, brutalised, and defrauded of all that belongs to childhood”, were the product of a rapidly growing urban society swelled by an influx of immigrants; others were orphaned by the American Civil War. This period was especially hard for children who lived in New York City. From 13 to 16 July 1863, a series of violent disturbances later known as the Draft Riots or Draft Week broke out in the city. In the course of these events, the largest civil insurrection in American history, two hundred and thirty children had to be evacuated from the Colored Orphan Asylum, which was ransacked and burnt to the ground by the furious mob. The street urchins in Brown’s pictures are remarkably healthy, well-scrubbed, and cheerful. Reality, however, was quite different: accelerated growth brought with it a good deal of poverty, hunger, social inequality and child exploitation.

The street urchins in Brown’s pictures are remarkably healthy, well-scrubbed, and cheerful. Reality, however, was quite different: accelerated growth brought with it a good deal of poverty, hunger, social inequality and child exploitation. Labour robbed minors of their childhood, but it was not until 1916 that Congress passed legislation to protect children, thanks to the Keating-Owen Act, which restricted and controlled child labour. The photographs of Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine offer a documentary account of immigration, and the crowding and poverty of thousands of children such as those painted by Brown, who would grow up in the streets of New York.

Towards the end of the 19th century, the United States had become an industrial power of the first order. The port of New York was a beacon attracting millions of people. In 1884, seventy per cent of American imports were channelled through the port’s docks. By 1900, the port of New York City was already considered the most important in the world, and became the great gate of entry for Europeans arriving in the USA between 1890 and 1954. During that period, twelve million immigrants entered the country through Ellis Island, the city’s main customs facility, and most of this population settled in Lower Manhattan. On 1 January, 1892, President Benjamin Harrison created the first Federal Office of Immigration, which on the very day of its inauguration took in seven hundred people arriving on three ships in search of a new life. On 2 January 1892, Annie Moore, a fifteen-year-old Irish girl who arrived in America together with her two brothers, was the first recorded underaged immigrant to be taken in at Ellis Island.

After disembarking in America, the new arrivals had to respond to a questionnaire including twenty-nine questions, prove that they possessed a capital of no less than twenty-five dollars to help them start their new life, and pass a general health examination. A mere two per cent of those who sought entry to the country are estimated to have been turned back, due in most cases to issues related to polygamy, criminal records, anarchist activities or infectious diseases.

Today, more than one hundred million Americans can trace their ancestors back to Ellis Island. The island was named after Samuel Ellis, who purchased it in 1785, and currently houses the impressive Immigration Museum.

Children on the Beach

The well-known resort was a source of inspiration to painters, writers and film-makers. The history of this strip of land that stretches into the sea to the south of Brooklyn is a reflection of the social and economic transformations that took place between the last third of the 19th century and the Second World War.

Coney Island was originally the western-most of the outer barrier islands in Long Island, but became a peninsula after Coney Island Creek, which separated it from the New York borough of Brooklyn, was filled in. Called Conyne Eylandt by the early Dutch settlers because of the great amount of rabbits which apparently inhabited the island (konijn meaning “rabbit” in Dutch), its beginnings as a place for leisure and recreation date back to the period when New York City was fast becoming America’s financial, industrial and cultural capital.

In the decades following the American Civil War a rapid process of urban expan- sion and industrialisation took place in the former New Amsterdam, as the city reinvented itself in a rush of change and innovation. These swift transformations in social patterns, working life and income levels all led to the need for New Yorkers to find ways of escaping the stress and strife of modern living. While the most exclusive resorts – such as New Port, on Rhode Island – were reserved for the elites, Coney Island became a place for relaxation and release that was open to all, from workers to the upper classes.

In a very short period of time, the island – at a distance of only 20 miles from Manhattan – went from being the relatively isolated and solitary retreat extolled by Walt Whitman to what began to be known as “the greatest watering-place in the world”. Its nearness to the centre of the city, and the rapid development of communications, made Coney Island the tourist site of choice during the second half of the 19th century and the first few decades of the 20th century. In 1867 the first railway connection to the island was put in place, and by the 1880s four lines were already in operation, carrying fifty- seven trains every day and conveying a constant flow of visitors to the stop at Brighton Beach Hotel, where on busy Sundays more than one hundred thousand travellers arrived. By boat, holidaymakers were also able to reach the old pier on West Brighton Beach, and this mode of transport was used by more than one and a half million people, in 1882 alone, to visit Coney Island.

The transformation of Conyne Eylandt into an amusement site began in the 1870s, at the time of the centenary of American independence. The area soon filled up with hotels, parks, concert halls, dance halls, restaurants, casinos, race-tracks… Some of the offers of amusement were quite unique: visitors could ride to the top of a one-hundred-foot view-tower aboard a steam-powered elevator, visit a pavilion that housed a camera obscura, or stay at a hotel in the shape of an exotic giant elephant. These early attractions paved the way for large amusement parks such as Luna Park, the Steeplechase and Dreamland, which were built in the course of the next few decades, making the area so famous that historian John F. Kasson would come to define it as “the laboratory of the new mass culture”.

Coney Island was the place where Buffalo Bill and Houdini premiered their shows, where the roller-coaster that marvelled Charles Lindbergh was invented, and where the first hot-dogs were consumed. The canvas we present here is one of the numerous works that Samuel S. Carr painted at Coney Island between 1879 and 1881. The coast at this time was divided into four distinct sections: Norton’s Point had assumed an unsavoury reputation as an area frequented by con men; West Brighton – the area Carr visited most – was the landing point for the steamboat traffic of excursionists; Brighton Beach became the fashionable place to go; and Manhattan Beach was the exclusive part, where street merchants and showmen were prohibited.

Fifth Avenue at Washington Square, New York

Following his return from Paris in 1889, Hassam lived at 95, Fifth Avenue, a few steps from Washington Square. He chose to live on a part of Fifth Avenue that resembled the tree-lined boulevards of Paris.

At the end of the 19th century, the main character in Wharton’s novel The Age of Innocence wondered at the urban make-up of the city: «So New York is a labyrinth? It had seemed so plain and straight to me, like Fifth Avenue. With all its cross-streets numbered!».

There was and still is a straight, immortal fault running through the honeycomb of Manhattan streets from the north to the south of the island, starting at the Harlem River and ending at Washington Square Park, that divides the city in two sections, the East Side and the West Side, from which numbered streets stem perpendicularly. This was the avenue chosen by Hassam as his dwelling place. It was also the abode of New York’s social elites, who had begun to move there in the 1860s, and to this day continues to be one of the grandest and most expensive streets in the world. The stretch of Fifth Avenue overlooking Central Park would come to be known, as from the 1920s, as Millionaire’s Row, because of the many rich New York families who built their stately mansions there; a good example of such buildings was the Vanderbilt family palace.

Fifth Avenue, the second longest street in New York after Broadway Avenue, extends for almost nine miles. Its history of splendour began in 1862, when Caroline Schermerhorn Astor took up residence on the south-eastern corner of 34th Street, at a spot which later, in 1893, would become the legendary Hotel Astoria.

The first commercial building on Fifth Avenue was erected by Benjamin Altman, who purchased the north-eastern corner of 34th Street in 1896 to set up his department-store business, thereby creating an exclusive shopping district that attracted New York’s high society ladies and the companies that catered for their needs. Fifth Avenue houses some of the most iconic buildings in the city’s Midtown and Upper East Side districts, including the Empire State Building (for more than forty years, the tallest in the world), Mount Sinai Hospital, the New York Public Library, the Rockefeller Center, St. Patrick’s Cathedral, the Metropolitan Museum of Art or the Guggenheim Museum. This part of Manhattan set the scene for films like Fifth Avenue Girl (1939), starring Ginger Rogers, and served to inspire the photography of Alfred Stieglitz.

Hassam’s canvas probably depicts the painter’s block of brownstones, and perhaps the sidewalk in front of his studio apartment. Nearby, on Washington Square, the Washington Arch would soon be completed. Designed by Stanford White and built in white marble to commemorate the centenary of George Washington’s investiture as president of the United States, the monument was suggested by the Arc de Triomphe on the Champs-Elysées in Paris.

During the early 1890s Hassam painted a number of views of Fifth Avenue in all kinds of weather and soon became well known for them. The fashionable thoroughfare would fill with every type of carriage, from spacious berlins, open- sided surreys and elegant four-horse landaus to small buggies and slim coupés driven by coachmen. Ladies who were well aware of the importance of dress and decoration floated down the boulevard wearing bustles and long white mitts, under the protection of parasols, on their way to modernity. In the words of Edgar Allan Poe, who spent his last few years in New York, «the display of wealth served the same purpose as the old heraldic emblems of royalty».

Childe Hassam also illustrated an article on Fifth Avenue by Marianna G. Van Rensselaer for The Century Magazine in 1893, and in 1899 published Three Cities,a book including reproductions of the vistas he had painted of his favourite cities: Paris, New York and London. In 1919 he bought a house on Long Island, which became his permanent summer home, and it was there that he painted many of his last canvases of the city.

In the Park. A By-path

In 1889, William Merritt Chase sent several paintings of parks to the Paris World’s Fair. These small-sized, unpretentious pictures depicted different nooks and corners of settings in everyday life, and did so in an innovative way, often adopting Impressionist ideas such as a close attention to nature and the use of the changing effects of light.

The refreshing scenes of city parks came at an important stage in the painter’s career, and earned him recognition from the critics and the public. The scenes, painted soon after the great exhibition of French Impressionism that Durand-Ruel had organised in New York in 1886, introduced a fundamental change in the work of Merritt Chase, who began to devote his efforts to this mode of open-air painting.

For several years, Chase made small, quickly executed studies in Prospect Park, Brooklyn; and after moving to Manhattan he began to paint Central Park. Critic Charles de Kay – the brother of New York painter Helena de Kay – observed that “[Chase] has hit upon a discovery which is yet to be made by a very great proportion of the inhabitants of New York. He has discovered Central Park. Not that most New York people do not know there is such a place, and are not more or less proud of it, but comparatively few of them ever go into it, and when they do go, they rarely see anything”. Indeed, through his painting the artist succeeded in bringing to the foreground the first great public park in the United States, and turned each of his scenes into a tribute to city parks as part of the North American environment.

Towards the middle of the 19th century, the New York Metropolitan Area had experienced huge growth due to its rapid increase in population. The city was getting bigger and bigger, and open spaces were few and far between. This began to highlight the need for a large public park where town dwellers may enjoy leisure and relaxation, much as they did in the Bois de Boulogne in Paris or in London’s Hyde Park. The idea immediately gained support from wealthy, influential New Yorkers, who realised that a project like Central Park would add a touch of distinction to the city and place it at the level of the great European capitals. On 21 July, 1853, the New York State Legislature settled upon a 700-acre plot of land in the centre of Manhattan for the construction of the park. Four years later, a landscape design contest was held. Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux developed what came to be known as the “Greensward Plan”, inspired by principles of English park and garden design, and this was selected by the Central Park Commission as the winning project.

The part of Central Park that is depicted in Chase’s picture is a by-path running along the remaining foundation wall of Mount Saint Vincent, a convent for the Sisters of Charity situated in the north- east corner of the Park near 105th Street and Fifth Avenue. In 1847 the Roman Catholic Order purchased the area that was originally the site of McGown’s Tavern, built in the 1750s. The convent, which included a boarding school for several hundred female students, was incorporated as park land in 1859 under Olmsted and Vaux’s development of Central Park. The building served briefly as a military hospital during the Civil War, and then the old convent building reverted to a tavern that catered to the wealthy carriage trade. Mount Saint Vincent burned to the ground in 1881, but was soon rebuilt as another saloon, now named the McGown’s Pass Tavern. It was torn down in 1917 by the New York reform mayor, John Purroy Mitchel, who desired to maintain the natural qualities of the park. The foundation wall, but not the pathway that is seen in the picture, still remains today. The models used by Merritt Chase were his wife, Alice Gerson, whom he had married in February of 1887, and their eldest daughter, Alice Dieudonnée – nicknamed Cosy – who was about two and a half at the time. She and her sister Dorothy were often painted by the artist.

William Merritt Chase was a key figure of the New York art world during this period. A teacher at the Art Students League, and the founder of the New York School of Art, he was one of the most distinguished tenants at the famous Tenth Street Studio Building in Greenwich Village.

Nedick's

Nedick’s, painted in 1970, focuses on the façade of one of the restaurants belonging to a chain of fast-food outlets created in the city of New York. The chain had branches in different American cities, and it became immensely popular among New Yorkers for its orange juice and its hot-dogs.

The name of the brand was a fusion between the surnames of its creators, Robert Neely and Orville Dickinson, who opened the first Nedick’s restaurant on the ground floor of the Hotel Bartholdi, on 23rd Street and Broadway. The chain’s mottoes – “Good food is never expensive at Nedick’s” and “Always a pleasure” – were known to all New Yorkers, and the restaurant’s characteristic white signboards with orange lettering on them were exhibited in the town’s most busy streets. Nedick’s soon became an institution in Manhattan, whose dwellers considered it as famous as Nathan’s, on Coney island. According to The Daily News, the establishment’s fame thrived on tales such as the story about a young Gregory Peck subsisting on the restaurant’s typical nine-cent breakfast during his lean years as a young, aspiring actor. Nedick’s sponsored the New York Knicks, and sports commentator Marty Glickman’s slogan on the radio, every time the team scored a point, became equally well-known in the city: “Good... like Nedick’s!”. When speaking of Nedick’s, another inevitable reference is of course Martin Scorsese’s film Taxi Driver, shot in Manhattan, in which the restaurant’s brightly-lit neon sign appears in different locations of the city.

Battery Park

The Battery is a public park located on the southern tip of Manhattan Island, offering a privileged view of the port of New York.

This part of the city is known as The Battery since the 17th century, when the area was part of the Dutch settlement of New Amsterdam and under the protection of a ‘battery’ of cannons. It was here that the famous Castle Clinton fortress was erected during the War of 1812 between the United States and Great Britain. Before Ellis Island became the gate of entry for immigration into the United States, Castle Clinton functioned as the immigrant reception centre; over eight million people were processed there between 1855 and 1890.

It is also the point of departure of the ferry boats that leave for Liberty Island, where one of the most important symbols of New York, the Statue of Liberty, is to be found. The famous statue was a gift from the French people to the United States on occasion of the anniversary of the country’s independence. The colossal figure of a woman, towering to a height of 150 feet, was an interpretation of Libertas, the Roman goddess of freedom. Designed by sculptor Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi, its assembly and internal structure were the responsibility of Gustave Eiffel.

Because of its location, its history and the vistas it has to offer, Battery Park attracts many New Yorkers. It was the place chosen by Reginald Marsh to paint one of his first oils on canvas. In his paintings, drawings and photographs the artist, who came from a well-to-do family, always preferred to depict scenes from the everyday life and leisure time of the working classes. His art transports us to the New York of the 1920s and 1930s, and it was during this period that he painted The Bowery, Coney Island, the subway or 14th Street. Marsh’s depictions of burlesque shows, jazz clubs, dance halls, crowded beaches, and men and women strolling through the streets of Manhattan, became immediately popular because they struck a very familiar chord with New Yorkers. His style, fresh and attentive to detail, was clearly influenced by his period as an illustrator, and his paintings featured numerous elements of daily life, such as billboards announcing the ‘freak shows’ on Coney Island, or signs announcing cheap hotels and barber shops. The artist was endowed with an extremely keen sense of observation, a sharp wit and an enormous ease for making acute social and satirical comments in his pictures of city life. The attention to detail exhibited in his work is a common characteristic of the documentary style of artistic expression during the period.

Marsh had studied Fine Arts at Yale University, where he collaborated as an illustrator on The Yale Record magazine. Following his graduation in 1920 he worked doing freelance sketching in New York, and from 1922 to 1925 became staff illustrator on The Daily News, where he published a daily column with vignettes devoted to the theatre and other city scenes. At the time Marsh also painted backdrops for the Greenwich Village Follies theatre, and had just worked with decorator Robert Edmond Jones on the design of sets for the Provincetown Players. His theatrical work and interests would clearly influence the style of some of his paintings.

The painting at the Museo Thyssen- Bornemisza shows a view of Batter Park with steamboats in the background. Three women clad in the fashion of the 1920s enter the sunny setting, where the effect of the wind is very accurately conveyed by the billowing smoke from the tug boats in the harbour and one of the women holding on to her hat in the breeze. The picture is painted in the open air, something Marsh would do in his early compositions, while in later work he relied on sketches and photographs that he took himself and greatly altered in the creative process in his studio to produce results that were not literal copies, since the artist considered photographs to be mere sketches, a kind of visual annotation rather than a finished work of art. The themes in his photographs fit into the same documentary category as those of his contemporaries Berenice Abbott, Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans, but the use Marsh made of his own photographic images for the purposes of painting is closer to the technique of Ben Shahn or Ralston Crawford. Although the artist never considered himself a photographer, the quality of his photographic work as a reflection of an unrepeatable period in the history of New York places him among the indispensable master photographers of the time. In fact, three of Reginald Marsh’s photographs were included in the exhibition 70 Photographers Look at New York, organised by Edward Steichen at the Museum of Modern Art in 1957.

Continues on the first floor

On the map you can see the rooms where the masterworks are located.

Throbbing Fountain, Madison Square

John Sloan had arrived in New York in 1904 following his friend and mentor Robert Henri, one of the fathers of American modernity, who had begun to teach at the New York School of Art.

He was immediately attracted to the bustle the elevated trains, the busy life of avenues and streets – which he began to depict in his paintings. Working as an illustrator for The Philadelphia Inquirer and The Philadelphia Press he had developed a keen eye that would allow him to depict with accurate detail and liveliness the day to day existence of some of the most popular districts in Manhattan. Like Henri, Sloan advocated a new kind of realism in North American art; both men wished to break away from the humdrum themes of the National Academy of Design, and paint contemporary life as the Impressionists had done earlier.

An event took place in New York in 1908 which was to be a turning-point for North American art: the exhibition The Eight at the William MacBeth Gallery on 27th Street. The show became a gesture of defiance aimed at the Academy by Robert Henri and his inner circle. As a member of the Academy’s jury, Henri was incensed at the constant rejections of the work of John Sloan, and concluded that he must find a way to publicly express his position of open rebellion. The show, which opened on 3 February, 1908, exhibited works by Henri, Sloan, Arthur B. Davies, William James, Glackens, Ernest Lawson, George Luks, Maurice Prendergast and Everett Shinn. It became one of the milestones in the birth of American modernity. Because of the realism of Sloan’s work and the themes of the group as a whole, in the mid 1830s The Eight were renamed the Ashcan School. The work of these painters implied a thematic, rather than a stylistic, revolution in the history of American art.

It became one of the milestones in the birth of American modernity. Because of the realism of Sloan’s work and the themes of the group as a whole, in the mid 1830s The Eight were renamed the Ashcan School. The work of these painters implied a thematic, rather than a stylistic, revolution in the history of American art. Henri encouraged Sloan and his other pupils not to turn their back on their emotions, and to strive for new means of artistic expression. The members of the group were also responsible for another of the most influential events of the period in the sphere of art: the Armory Show, in 1913, which introduced contemporary European avant-garde movements to the United States. The International Exhibition of Modern Art was held at the armory of the National Guard’s Sixty-ninth Regiment, on Lexington Avenue in New York City, offering the American public a sample of European works of art together with exhibits by American masters. The event became a veritable cultural earthquake, leading to many heated debates about the nature of modern art. In a cruelly ironic twist of fate, the Armory Show sidelined the very artists who had helped to set it up, while confirming the triumphant advance of the latest trends in French painting.

In Throbbing Fountain John Sloan reveals to us a motif which the artist found particularly captivating. A year before painting the picture, he had already mentioned the famous New York square in his diary: “The fountain in Madison Square, which men and women stare at raptly, in some cases feeling its sensuous charm”. In 1906, Sloan and his wife had moved to 23rd Street West, near the spot that is depicted in the picture. The artist strolled through Manhattan for several hours every day, and frequently found inspiration in his own neighbourhood.

Madison Square district, whose name is associated with James Madison, fourth president of the United States and the main author of the country’s Constitution,was then a neighbourhood of small houses above which towered the Flatiron Building, or Fuller Building, built in 1902 and painted by Sloan himself in his canvas Dust Storm, Fifth Avenue, now owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Designed by the great architect Daniel H. Burnham, the Flatiron Building got its name from its triangular shape, and was erected to spearhead the creation of a second financial hub to the north of Wall Street. Following its inauguration, a curious and amusing phenomenon was discovered: the way in which the building channelled the winds created strong currents of air that became famous for lifting the skirts of the ladies of the period.

The building’s revolutionary steel structure was covered by a façade that blended in perfectly with its historical surroundings, and New Yorkers were captivated by the result. Sloan’s neighbourhood was also the site for the first two venues of the Madison Square Garden, built in 1879 and 1890 respectively.

Metropolis

New York is a rich backdrop for any kind of artistic activity. Intellectuals, painters, musicians and film-makers all sought out the magic of this city. In Leaves of Grass (1855) Walt Whitman praised it as “the acme of the Western world”. Jack Kerouac made poetry out of the city’s life, and latter-day writers and artists who have lived there or still do – Paul Auster, Philip Roth, Tom Wolfe or Woody Allen – have felt the seduction of its indomitable spirit.

When Grosz arrived in New York he liked it much more than he’d been led to expect by the films he’d seen about the city. But he had dreamed about it many years previously. Walter Mehring, who met Grosz in 1916, referred to the latter’s painting Metropolis as “Reminiscences of the Entrance to Manhattan”, owing perhaps to the fact that many of the preparatory drawings for the painting were imaginary renderings of New York.The Austrian poet Theodor Däubler, in an early article about the painter, had already noted that “his conception of the big city is really apocalyptic” when describing a drawing of 1916 entitled Memory of New York.

To Grosz, American cities were a dream; he didn’t know them, but had come to love them through books. An indefatigable reader since childhood of the novels of James Fenimore Cooper (cowboys and Indians appear several times in his paintings) Grosz idolised Chicago gangsters, and sometimes posed for friends wearing a gun and mobster hat. Americanism was in his case an expression of protest against German conservatism. In 1914 he enlisted as a volunteer and spent time in the trenches, an experience that was to mark his entire generation. America became an enemy nation, its soldiers parading through Berlin after the Armistice. But Grosz’s admiration for the United States was unshakeable, and in 1916 even prompted him to change his name from Georg to George Grosz, which he would use for the rest of his life. The fascination of European intellectuals for everything American stemmed from their perception of America as a true symbol of modernity.

In 1932 Grosz was invited to the United States as guest professor by the New York Arts Students League; a year later, he had already taken up definite residence in the country. Deprived of his German passport in 1938, he became an American citizen. He accepted temporary employment at a drawing school while waiting for commissions to start coming in from the big magazines – Harper’s Bazaar, Vanity Fair, The New Yorker, Esquire – which were going through their golden period at the time. He was famous for his illustrations in Germany and the whole of Europe, and made a lot of money from his work. In the United States, whose visual culture was much more powerful and up-to-date, his success seemed to be guaranteed. He returned once more to Germany to gather up his family, sell his house and studio and liquidate his assets, before moving back to America to begin a new life. He later learned that a few days after sailing from Germany the Gestapo had come in his search. The relief of escaping the dung heap his native country and the rest of Europe had by now become gave the artist the highest hopes.

In 1936 Grosz painted The Port of New York. Although the ships and office buildings in the picture convey the bustle of trade, the artist does not stress the humming crowds of the great metropolis, but the spectacular grandeur of the city’s skyline. As was the case with so many other newcomers, the painter had been bewitched by New York: “I patted myself on the back, albeit in my imagination... And after boarding the fast elevator, which did not stop in its rapid ascent from the first to the thirty-first floor, I felt I was floating in the clouds, and very pleased with myself. ‘Not bad,’ I thought. ‘A splendid country, this America...’ At forty-four, I was still relatively young, and my dream was more alive than ever”. But this was no more than a wish, since Grosz was unknown in America. His ironic fury gradually grew more serene, and the biting style of his Weimar and Berlin years disappeared, giving way to a dramatic change in the artist’s American period. From a distance, he observed the victory of Fascism and Nazism with bitterness, and realised they had confirmed his early presages of impending doom: the Second World War, the Spanish Civil War, the concentration camps and the death of friends.

In 1946, after living for more than a decade in exile and experiencing serious financial difficulties, Grosz penned his memoirs. In 1958 he returned to Europe, to what was then Western Germany. He died on 6 July, 1959 in West Berlin, after falling down the stairs following a night of heavy drinking.

Metropolis, which had been included in a German public collection in the midtwenties, was sold by the Nazi regime to Curt Valentin, a German art dealer who emigrated to America taking the picture with him. Thus it came to pass that Grosz recovered his iconic painting in the city of New York.

Grand Central Terminal

Born in Russia but a naturalised american citizen, Weber was one of the great synthesisers of European art innovations at the beginning of the 20th century. The artist, who had emigrated to New York with his parents when he was ten years old, completed his American training thanks to a fruitful stay in Paris, and managed to achieve a unique and quite personal painting style which transmits the dynamic qualities of the huge city.

Grand Central Terminal represented the frantic bustle of a growing town. The station had been built to replace and update the old depot after a horrific accident involving two trains that collided in the Park Avenue tunnel and caused the death of seventy people.

The tragic event led the New York authorities to impose a definite ban on steam engines within the city, and to the creation of a power-driven railway system which required the whole network, and the terminal station itself,to be completely rebuilt. The new terminal opened its doors to the public at midnight on the 1st of February, 1913, and was described by the newspapers as one of the “glories of the metropolis”. The station also provided renewed commercial thrust to the Midtown Manhattan area, where many new shops, restaurants, offices and hotels opened up for business. The competition for the design of the new main building was won by Reed & Stem, who were in charge of all the functional features of the project for the wealthy Vanderbilt family, the owners of the station, while the Warren & Wetmore architecture studio were responsible for designing the Beaux Arts building that is seen from the street. The result was a great architectural achievement that is divided into two storeys, both of them below ground, with 26 railway tracks on the lower level and 41 tracks on the upper level. The terminal includes a total of 44 platforms, marble floorings, sumptuous chandeliers, and a central dome, decorated by French painter Paul César Helleu, representing a view of the constellations against the night sky.

The Vanderbilts, who had made their fortune in shipping and railways, spared no expense: the enormous Main Concourse (125 feet high) was covered with marble from Tennessee, held up by 1,500 columns and reinforced with steel, and caused a sensation among New Yorkers. The grandiose architectural undertaking, which also houses shops and restaurants like Oyster Bay (also inaugurated in 1913, and whose dome-shaped ceilings are the work of Valencian architect Rafael Guastavino) immediately became a source of inspiration for photographers, writers, painters and film-makers. Audiences have been thrilled by the famous setting in films like Brian de Palma’s The Untouchables and Alfred Hitchcock’s suspenseful North by Northwest. The station’s waiting-room is where Holden Caulfield, the main character in J. D. Salinger’s novel The Catcher in the Rye, decides to spend the night during his escapade in New York, and it also served as the backdrop for one of the creations of the well-known choreographer, Merce Cunningham.

Max Weber’s painting Grand Central Terminal focuses on the façade of the building, which dominated downtown Manhattan before the arrival of the city’s skyscrapers. Built in limestone, the façade features three great arches that are separated by paired Corinthian columns supporting the entablature, the slightly curvilinear frontispiece that rounds off the pattern on each side, and the clock with the sculpture of Mercury at the crown of the whole structure. Weber’s aim in the painting was to plastically express the feeling of sheer energy and speed of the rush hour by means of an interpretation of the building’s façade. The picture’s style evidences the impact upon the artist of Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, which Weber had seen at the Armory Show in 1913. The formal Cubist reduction of the human figure in Duchamp’s canvas becomes extremely dynamic when captured in the successive postures adopted by the body as it descends the stairs; the painting was considered the most scandalous exhibit at the celebrated show, and deeply affected Weber. Grand Central Terminal also displays technical similarities to Gino Severini’s The North-South (1912) depicting a bustling metro station in Paris.

Weber was one of the more than three hundred artists represented at the Armory Show, in addition to being personally committed to the avant-garde and to bold and innovative circles such as the one surrounding photographer and art dealer Alfred Stieglitz, whose Gallery 291 had become a meeting point for artists and intellectuals, and a place of exchange devoted to creativity and theoretical elaboration. With Max Weber’s initial collaboration, and that of Edward Steichen and Marius de Zayas a little later, Stieglitz organised the first exhibitions ever to display the works of Matisse, Cézanne, Picasso, Braque, Rousseau or Severini in North America. Like Weber in his painting, Stieglitz in his photographs captured and conveyed the vitality and sheer energy of turn-of-the-century New York, and transformed it into the very image of modernity.

In Port

1915 was a significant year in the life of Albert Gleizes. After being called to arms and discharged some time later, he married Juliette Roche, the daughter of Jules Roche (a French politician, the godfather of Jean Cocteau). The couple, who were committed pacifists, managed to get away to New York for what was to have been a three-month stay and lasted for three years, interspersed with trips to Spain and the Bermudas. The Gleizes were made welcome in New York by Francis Picabia and Marcel Duchamp. The latter, having by then adapted perfectly to the frantic pace of the city, introduced them to a circle of collectors that included Louis and Walter Arensberg.

The Gleizes found accommodation in the same building as Louise Carese, who told the amusing story of how one day, at the break of dawn, after a long and lively night, Marcel Duchamp ate a leg of lamb taken from the cold-box in her apartment; the meat belonged to Gleizes, who had no such refrigerating conveniences in his own home and kept his food in Carese’s apartment. After devouring the leg of lamb, the bone became a readymade on which Duchamp imprinted his gratitude by leaving it at the door of the Gleizes with a couple of banknotes attached to it. Everyone except the Gleizes themselves found this episode highly amusing; the couple did not quite appreciate Duchamp’s excesses and eccentricities, as was made obvious at the time by Albert Gleizes’s tendentious comments regarding the former’s Nude Descending a Staircase.

In New York, as Bernard Marcade tells us, Albert Gleizes exhibited a somewhat condescending and almost patronising attitude to Marcel Duchamp, who once attempted to put an end to Albert’s continual reprimands and remarks by replying, “My dear Gleizes: if I didn’t drink so much alcohol I would have committed suicide long ago”. In spite of the differences between them, in 1917 Duchamp invited the couple to his thirtieth birthday party, together with Picabia, Leo Stein and Roche, as recorded by painter Florine Stettheimer in her canvas La fête à Duchamp.

At the time, New York’s Greenwich Village was one of the places where new ideas met and came together. John Reed paid tribute to the famous Manhattan neighbourhood in his 1913 poem The Day in Bohemia. These were the wild days, when Duchamp, Gertrude S. Drick and a merry band of assorted subversives brought the Dada movement to America, and at one stage mounted the arch in Washington Square to proclaim the ‘Independent Republic of Greenwich Village’. Albert Gleizes, whose nature was a little more subdued, left the group and moved to a quieter place in Pelham, about ten miles from New York.

During these years Gleizes painted a series of vistas of the city, and especially of the port area. In Port is not only a manifesto for Cubism, but also a tribute to two cities. The painter did a lot of preparatory work, including four vertical compositions produced in New York between 1916 and 1918, and obviously invested a great deal of effort in the picture. When speaking of some of the New York references of In Port, the suspension cables of the Brooklyn Bridge – an icon of the city and one of the most beautiful bridges in the world – immediately come to mind.

Originally designed by Prussian engineer John Augustus Roebling, the construction of the bridge was taken over by his son, Washington, following Roebling’s death after an accident at Fulton Landing in 1869. Washington, however, was paralysed as a result of a gas embolism, which he suffered while helping with the excavation work in the river basin, and lay prostrate in bed for most of the duration of the work. Washington Roebling’s wife, Emily Warren Roebling, then took charge of supervising the work, and was in fact the first person to cross the bridge upon its inauguration in 1883. As ill luck would have it, a tragedy occurred during the opening ceremony, when several thousand people, including President Chester A. Arthur, crowded onto the structure. Someone shouted that the bridge was about to collapse, causing a stampede in which twelve people died.

In spite of these disasters, the bridge soon became an endless source of inspi- ration to poets, writers, and painters like Albert Gleizes. It has also been – since the days of silent movies – one of the most frequently filmed constructions in the history of the cinema, and is depict- ed in numerous films ranging from Ted Wilde’s Speedy to Martin Scorsese’s Gangs of New York.

The ship’s prow in Gleizes’s painting is a reminder of the many vessels from all over the world that docked in the port of New York. That was indeed the final destination of the Titanic when it left Southampton in 1912. Benjamin Guggenheim, the father of Peggy Guggenheim, perished in the shipwreck of the famous transatlantic. The latter’s brother, Solomon Guggenheim, bought this picture in 1930.

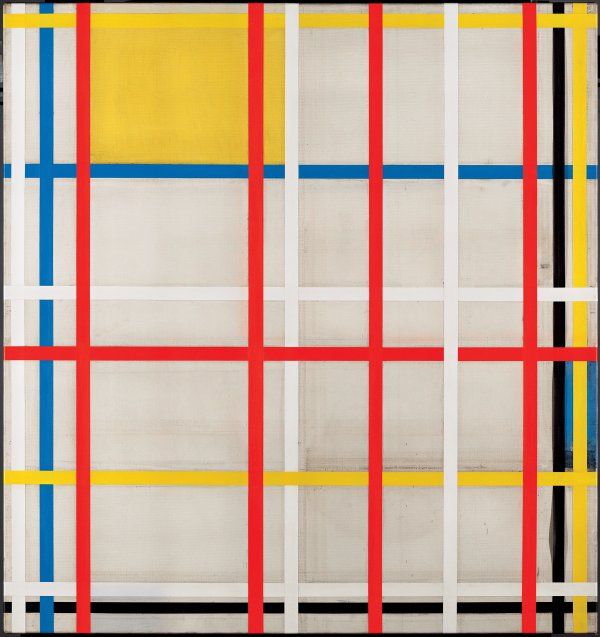

New York City, 3 (unfinished)

The Second World War had driven Piet Mondrian to London in 1938, and two years later – aghast at the bombings of the British capital, and the invasion of Paris by the Nazis – he decided to accept the invitation to America from his friend Harry Holtzman, to whom he wrote: “I’m ready to come”. On 23 September, 1940, Mondrian boarded the Samaria, on the Cunard Line, which left from the port of Liverpool and arrived in New York on the 3rd of October. Piet Mondrian would spend the last years of his life in New York. The exodus of European artists during the war was massive; in their new physical and intellectual environment, they all experienced a transformation that changed the nature of their production.

In 1941, soon after his arrival in America, Mondrian gave a written account of his artistic credo: “The metropolis reveals itself as an imperfect but concrete determination of space. It constitutes, in itself, the expression of modern life. It produces abstract art: the definition of the splendour of dynamic motion. [...] A work of art is only ‘art’ ina smuch as it defines life in its one immutable aspect: pure vitality”.

The giant quadrangle of the city, which spread over more than twelve miles covering the island like a rational maze of streets and avenues, is transformed in Mondrian’s painting into a grid of straight lines, rectangles and primary colours in the series entitled Studio-Wall Compositions, which was found after the artist’s death in his last studio, on 59th Street. All his late work seems to be a tribute to the orthogonal design of Manhattan.

Manhattan Island’s original structure dates from the 1811 Commissioner’s Plan. The plan represents a deviation of 28.9 degrees from the cardinal points, leading to one of the most marvellous phenomena of the city, when the sun aligns with the street layout twice a year, and creates what is known as ‘Manhattanhenge’. The plot of the streets and avenues in New York, the size of its blocks and the height of its buildings, derived from a series of town planning and development criteria that contributed to the unique makeup of the city.

This uniform mesh was developed on the basis of a crosswise pattern of avenues, running from north to south, and streets, running from east to west. The resulting grid determined the size of the city’s blocks. The entire network then adapted to the shape of the island, producing 12 avenues and 155 streets.

New York also experienced a spectacular process of evolution in the third dimension. The erection of ever higher buildings, encouraged by technological discoveries and advances, led to a free- for-all, apparently limitless race to the sky which in fact had to be curbed through regulation in 1916. Skyscrapers changed the appearance of the city forever.

However, it was not only town planning, architecture and the city lights of Manhattan that seduced Mondrian. He was also an enthusiast of music and dancing. The artist had an enormous collection of jazz records,regularly attended Josephine Baker’s Ballets Nègres, and was a passionate follower of the Ballet Russes of Sergei Diaghilev. An admirer of the films of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, his musical leanings were described by his friend Theo van Doesburg’s widow as follows: “It is well known that Mondrian was a devotee of social dancing, and had left the waltz behind to take foxtrot and tango lessons; whatever the music that was being played, he would perform his dance steps in an extremely personal and highly stylised fashion”.

La metrópolis trepidante y el ritmo frenético aparece en su pintura dedicada al Boogie-Woogie, un estilo de blues rápido y bailable interpretado al piano, que nació en el sur de los Estados Unidos y llegó en 1938 a Nueva York, causando furor, en un famoso concierto organizado por John Hammond en el Carnegie Hall. Mondrian solía asistir al Cafe Society Downtown, en el Village, donde actuaban los mejores músicos. No era la primera vez que el nombre de un baile aparecía en una de sus obras, ya lo habían hecho en Foxtrot (1929-1930).

The bustling metropolis and the frantic pace of the city are conveyed in the picture Mondrian devoted to the boogie-woogie, a fast, danceable form of blues that was performed on the piano and reached New York in 1938, after emerging from the South of the United States. The new style caused a furore following its introduction by John Hammond in the course of a famous concert at the Carnegie Hall. Mondrian was a frequent patron of the Cafe Society Downtown, in the Village, where the best musicians of the time performed. He had already based another of his earlier paintings, Foxtrot (1929-1930), on a style of dance, and was the first artist to explore the influence of black music and jazz bands on art. Dance probably served as a stimulus to his depiction of the frantic pace of life through the use of adhesive tape and primary colours on white canvases. The shiny surface of these materials created a contrast that highlighted other textures in the paintings. When attached and detached, the tapes also produced sounds in synchronisation with the movements of the body.

In 1942, Arnold Newman photographed Piet Mondrian in his studio at no. 353, 56th Street East. A room without furniture, an easel and a drawing table is all that we see. Mondrian had whitewashed the walls, upon which only hung red, yellow and blue-coloured squares of paper. The artist proudly displays his work in New York, a city that was full of attractions for a painter whose art would explode after his arrival in the Promised Land.

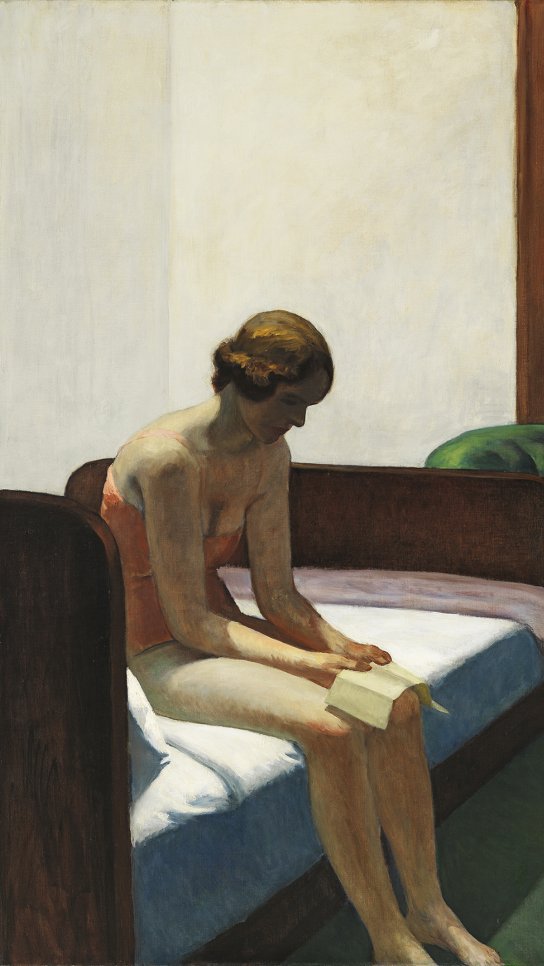

Hotel Room

Edward Hopper was born in 1882 in Nyack, New York State. The small town is located on the left side of the Hudson River, about twenty-five miles to the north of New York City. He studied at the New York School of Art under William Merritt Chase, John Sloan and Robert Henri.

Hopper travelled to Europe several times, and soon developed an interest in Continental art and culture, which were two of his passions. Among his other interests, some of his favourite themes included sailing, baseball, cycling, photography, Darwinism and Irish immigration.

Hopper came to New York in 1908, but did not take up permanent residence in the city until 1910. His first studio was on 59th Street East, near the work-place of his master Robert Henri, whose studio was located in the environs of the Queensboro Bridge, an iconic site in New York which the artist painted in 1913.

Scott Fitzgerald referred to the Queensboro Bridge as “the first promise of all the wonder and beauty in the world”, and film-maker Woody Allen would capture it on film in Manhattan, his celebrated movie of 1979. However, Hopper was not interested in picture postcards, and never painted Brooklyn Bridge, or the city’s skyscrapers, or even a yellow cab. The artist preferred freight trains, the Manhattan Bridge loop or the unknown restaurants on Greenwich Avenue.

At the 1913 Armory Show Hopper sold his first painting, Sailing, for 250 dollars to a cloth manufacturer from Manhattan. That same year he moved to his second studio, at his home on the north side of Washington Square, in an area that had been built in the Greek Revival style in the 1830s. The building in which he took up residence had been refurbished in 1884 to house the studios of artists, and among Hopper’s neighbours were Edmund Wilson, John Dos Passos and E. E. Cummings.

Ensconced in the safety of his new studio, which was in part a retreat and in part a watch-tower, Hopper was to capture the life of the bustling metropolis. From his rooftop he could view Fifth Avenue (where his paintings would be displayed for the first time at a show devoted to his work) and it was here, at his workshop and home in the Village, where most of his canvases – including the one selected here – were painted. Josephine posed for her husband in this apartment, in a rather cold place, far from the open fire, which provided adequate lighting. Looking at the scene in Hotel Room we may almost fancy we find ourselves before a passage in Manhattan Transfer, the novel by John Dos Passos, that has been transformed into painting. The painter’s wife could be playing the solitary, pensive character of Ellen, described in the second chapter of the novel, while the room she sits in might well be one of the suites in the Breevort Hotel, the establishment frequented by New York’s bohemian set, which was demolished in 1954.

Edward Hopper only left his New York home to spend his summers in New England. He built himself a house in Cape Cod, and this became his retreat by the sea, which he alternated with his Manhattan apartment.

Hopper was a tall, thin man; he could have been a Paris flâneur, donning his hat and mumbling some excuse before going out to lose himself in the streets of New York. He fixed his gaze on windows to capture the fleeting moment, and explored the loneliness of an American life that he then depicted in images imbued with a narrative sense. His great loves were the theatre and picture houses, and during periods of inactivity he would take refuge in his addiction to noir films of the thirties and forties. “When I was unable to paint I would spend a week or more at the cinema,” he used to say. Edward Hopper is one of the artists who have exerted the greatest influence on modern film; we may find his trace in the work of Alfred Hitchcock, Abraham Polonsky or Terrence Malick, and his pictures themselves are almost perfect movie stills, cinematographic compositions that reveal his passion for films.

Manhattan’s Whitney Museum of American Art houses the Hopper Legacy, a collection that was donated by the painter’s heirs in 1970 and includes 3,150 paintings, drawings, studies and etchings, together with the artist’s diaries. At the same time, the city of New York itself is a constant reminder of Hopper’s painting, whose imprint is present wherever we cast our eye, from the High Line elevated park to the old tracks of former trains.

Although Hopper visited Paris three times, and was a tireless traveller, his home and his world were always in New York, the city he knew best and most loved.

Untitled (Green on Maroon)

During the 1940s and 1950s the world capital of the avant-garde changed its location. Paris, which for a long time had been at the centre of the most radical and innovative transformations of artistic modernity, was eclipsed by the New York of the abstract expressionists. This surprising change came about as a result of the innovations of a unique generation of artists; a series of masters of different nationalities who came together in the great city and shattered established norms and conventions, spearheading a new and decisive stage in 20th century art.

Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Clyfford Still, Barnett Newman, Arshile Gorky, Hans Hofmann and Robert Motherwell were some of the artists who broke with the past through an art form that sank its roots in the European avantgarde. All of them lived through a key period in history, and embraced the legacy of the artists and intellectuals who had arrived from Europe in their flight from the Nazis. With their differing styles, which in some cases shared common ground, the members of what came to be known as the New York School of painting celebrated in their work the individuality and freedom of the artist.

Manhattan became the epicentre of the New York avant-garde. Meetings that went on until the wee hours of the morning were the norm at the Cedar Bar, on University Place, in Greenwich Village. It was at the Cedar, and the Artist’s Club –founded in 1949 – where the passionate masters of abstract expressionism drank, talked shop, organised shows and even came to blows, carried away by the very same impulsive nature that gave life to their art. Rothko was the star of postwar New York, although his temperament was slightly more subdued and he never felt too comfortable in rowdy places like the Cedar.

In the world of art his painting was also somewhat removed from the spontaneous, gesturally dramatic work of his contemporaries. Rothko saw his pictures as drama; as the depiction of a timeless tragedy. His paintings, of great spiritual intensity, stir the viewer with a strong feeling of emotion, as if they were an invitation to contemplative meditation. Robert Rosenblum characterised Rothko’s painting as “the abstraction of the sublime”. Robert Rosenblum characterised Rothko’s painting as “the abstraction of the sublime”. The artist believed that pure colour was the best vehicle for the expression of emotion, since it acted directly on the soul, stirring deep feelings within the beholder. In order to further increase the intensity of the encounter, the way in which works of art were exhibited was of key importance; an accurate display could heighten the experience. Within abstract expressionism his work is associated with what critic Clement Greenberg called “colour field painting”, a form that is very different from the gestural nature and the dynamism of Pollock’s or De Kooning’s action painting.

The canvas at the Thyssen-Bornemisza was painted in 1961, the year the MoMA devoted a solo exhibition to Mark Rothko in New York. The inauguration in 1929 of the Museum of Modern Art, together with the Armory Show in 1913 and the opening of Stieglitz’s Gallery 291, was crucial for the creation of a breeding ground in which the American avant- garde might develop. At the end of the 1920s, the need for an institution that was solely devoted to modern art, and that broke away from the conservative policies of traditional museums, became clearly apparent. It was at this time that Lillie P. Bliss, Cornelius Sullivan, John Rockefeller Jr., A. Conger Goodyear, Paul Sachs, Frank Crowninshield and Josephine Boardman Crane decided to come together and create the MoMA, which started out under the brilliant management of Alfred H. Barr Jr. Their aim was to help audiences to understand modern art, and equip New York with a great museum devoted to contemporary art. The response of New Yorkers was so enthusiastic that the museum had to be moved three times over the following ten years, in successive attempts to find a site that was big enough for its needs, until it finally came to rest in the building it still occupies today in Midtown Manhattan.

As important as the creation of the MoMA, in terms of advancing modernity in New York, and especially as regards the dissemination of American abstract impressionism, was the activity carried out by Peggy Guggenheim and Betty Parsons at their respective galleries. The Art of This Century Gallery, designed by Frederick Kiesler for the niece of Solomon Guggenheim and housed at number 30, 57th Street West, exhibited work by such masters as Rothko, Hofmann and Pollock. The artist, dealer and collector Betty Parsons also used her gallery, inaugurated in 1946, to promote emerging art and offer her enthusiastic protection to new artists.

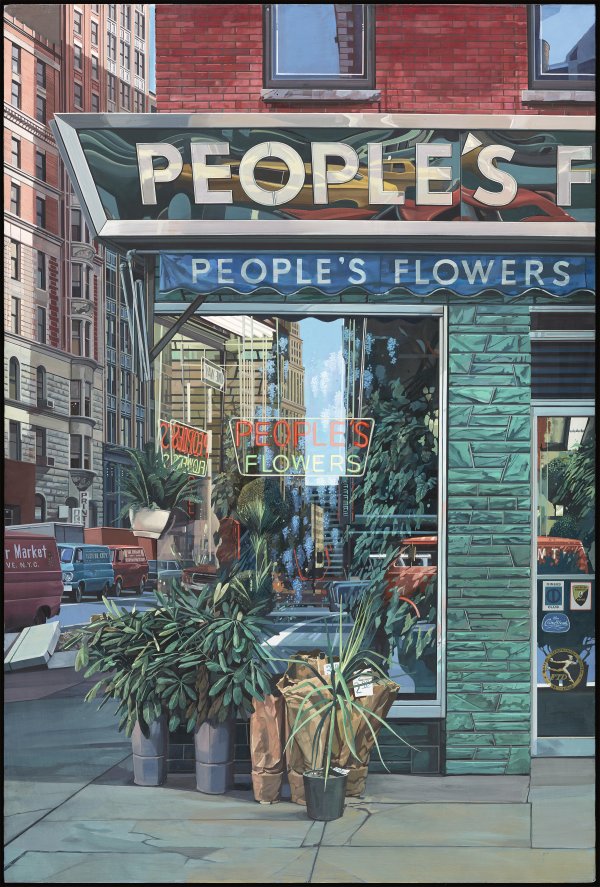

People's Flowers

People’s Flowers (1971) carries us to Sixth Avenue and 27th Street, to a flower-shop that no longer exists. When looking at the New York of Richard Estes we are made aware of the artist’s visual discoveries within the city, while at the same time witnessing the development, details and changes of the urban landscape.

Like Jimmy Herf, the character in Dos Passos’s Manhattan Transfer, Richard Estes traverses New York giving us the opportunity to rediscover the city through his works of art. To use the words of Sandro Parmiggiani, viewing his paintings causes “the resurgence inside of us of passage upon passage from the many pages written about New York”.

Telephone Booths

The geometry of the streets and brownstone buildings, the reflections in shop windows, the diners and telephone booths of Manhattan make their appearance on our journey through the work of Richard Estes.

The master of photographic realism transforms the streets of New York into his favourite theme, and like a latterday vedutista invites the viewer to stroll through a city where time seems to have come to a halt.

The starting point for the composition of his painting Telephone Booths (1967) was a series of photographs that the artist took of a row of public phone booths on Broadway, Sixth Avenue and 34th Street. The effect of the light striking the surface of the picture creates a game of mirror images, refractions and reflections through which the artist seems to be challenging us to capture the infinite possibilities of contemplation. A close examination of the scene and the reflections it contains reveal typical New York details emerging from the painting: the famous Manhattan yellow cabs; the characteristic “Don’t Walk” sign at a pedestrian crossing; a fragment of the logo of Macy’s department-store, another iconic establishment of the city. Created by Rowland Hussey Macy, who opened the first Macy’s store on 28 October, 1858, the original emblem of the chain featured a rooster, but Macy subsequently decided to replace it with the famous star, inspired by the tattoo he had traced on his arm during his sailing days aboard whalers. The department-store’s success resulted from a number of innovative sales and advertising techniques that transformed the whole industry, attracting swarms of customers. Among other novelties, Macy’s introduced a single-price system that did away with haggling, and newspaper adverts announcing the exact price of goods. Macy’s was the first business to be granted a license to sell alcoholic drinks in the city of New York, and also pioneered the figure of an employee dressed up as Father Christmas to greet children during the festive season.