Inclusive love

By Ignacio Moreno Segarra and María Bastarós

Inclusive Love views artworks from a new perspective different to that offered by traditional historiography to date. It surveys the collection through some of the themes, icons and people related to the sensibilities, culture and experiences of the LGBT community (lesbian, gay, bisexual and transsexual) which have always been present in art, though their presence has been invisible throughout the ages.

This route follows the layout of the museum’s collection, which is arranged chronologically and by cultural trends in western art.

The first part focuses on Old Masters, mainly from the Renaissance to the late nineteenth century. The iconography of the works, coupled with the artists’ lives, provides a useful insight into non-normative sensibilities, identities and desires from both a sensual and a social perspective.

The second part explores how these manners of feeling and thinking have progressively taken shape with the development of modern societies. From the emergence of the contemporary conception of homosexuality and the importance in this process of the spaces of freedom provided by the major cities to gender identity and the lack of a specifically lesbian iconography, the works illustrate a diverse range of personal experiences set in an environment that has become increasingly permissive, albeit with ups and downs. Art can be seen to have played a very active role in asserting these sexual, emotional and social claims.

Starts on the second floor

On the map you can see the rooms where the masterworks are located.

Portrait of a young Man as Saint Sebastian

Saint Sebastian is an indisputable icon for the gay community and has become imbued with various connotations over the centuries.

The story of Saint Sebastian, like those of many other saints, is drawn from various sources which gradually shaped his official history. Sebastian was an archer general attached to the personal bodyguard of Emperor Diocletian. After converting to Christianity, he not only spread his new faith but destroyed pagan symbols, for which he was sentenced to be tied to a tree and martyred with arrows fired by his fellow archers.

According to Professor Helena Carvajal González, the importance of the saint in the Middle Ages stemmed not only from the fact that he was the patron saint of ironsmiths but also from the protection he provided from the bubonic plague, a disease represented in art by a shower of arrows. During this period he was portrayed iconographically as a man of mature years, in order to reflect his position in the army, and bearing the instruments and palm of martyrdom.

Between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the saint began to be portrayed as a handsome adolescent boy, and this is how he appears in Renaissance works. The figure allowed artists to combine the protective nature of Christian culture with the newly discovered classical culture. Such was the prominence given to his physical appearance and nakedness that they eclipsed his moral and protective qualities.

The restoration of the Medici dynasty in 1537, represented by Cosimo I, was undeniably conducive to the flourishing of an art that followed in the wake of the Florentine Neoplatonic academy of Ficino, whose espousal of antiquity did not shun homoerotic references. Cosimo I surrounded himself with artists who were well versed in these theories and applied them to their own lives, such as the sculptor and goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini, the painter Gianantonio Bazzi, called “Il Sodoma”, and the historian and poet Benedetto Varchi.

Nevertheless, Cosimo I’s rule was rife with contradictions in its attitude towards homosexuality. He did not show the same tolerance as his Medici predecessors. On the one hand, the duke abolished the civic court in charge of prosecuting homosexuality, with which some 17,000 complaints had been filed, including those against Leonardo da Vinci and Sandro Botticelli. On the other, Bernardo Segni, a historian of the period, stated that, as an authoritarian and superstitious man, he enacted other strict laws, including one against sodomy. However, this law, under which Cellini was tried in 1557, proved ineffective owing to a lack of zeal not so much on the part of the magistrates as on the part of the duke himself. Cosimo, who had publicly celebrated many of Cellini’s witty remarks – such as when a rival called him a sodomite and he replied that sodomy was a vice of gods, kings and emperors and that he did not practice it because he considered himself “a humble man” – had the artist’s four-year prison sentence commuted to four years of home confinement. Even so, Cellini never found favour with the grand duke again.

Bronzino, who created the official image of the Grand Duke of Florence, had been romantically involved with his master Pontormo.

We find contradictions of this kind between two groups: the artists, an intellectual elite with artisan status who were weaving amorphous networks of everyday homosexual contacts (for example, in their workshops) in the growing cities and could show their affections more or less publicly thanks to their friendships with powerful people; and their patrons, well-educated men who promoted the arts and court life but were unable to renounce the powerful means of social and political control that persecuting homosexuality provided.Created by Bronzino at the height of the Renaissance, this Saint Sebastian is a good example of how depictions of the saint evolved towards physical embellishment.

This evolution can be clearly seen if we compare Bronzino’s work to that of the Master of the Magdalen Legend, executed around 1480 and also belonging to the collection. The earlier depiction is much more in keeping with medieval Christian iconographic tradition: the saint is standing, clothed, and bears the instruments of his martyrdom, the arrows.

However, Bronzino’s picture was painted to be shown privately in the homes of the nobility, who, like the artists of the period, practice and cultivated humanistic and Neoplatonic ideals. Works of this kind gave shape to the homoerotic interpretation of the Renaissance Saint Sebastian focused on his physical splendour.

In the opinion of Janet Cox-Rearick, an art historian specialised in Bronzino’s oeuvre, this is an early work executed by the artist while still under the influence of his master Pontormo.

The Renaissance biographer Giorgio Vasari described the two painters as inseparable and many scholars point out that although Pontormo adopted Bronzino – a practice that was not unusual among painters and apprentices – their relationship was much more than one of filial love. Bronzino, who lived with his master for years, benefiting from his trust and working in his studio, also had a poetic side and dedicated heartfelt sonnets to Pontormo when he died in 1557, calling him a ‘father’ and ‘friend’. Pontormo referred to him with pet names such a ‘Bro’ or ‘Bronzo’ in his private diary. In 1552, a few years before Pontormo passed away, Bronzino in turn adopted one of his own pupils, Alessandro Allori, showing that the system of artistic apprenticeship was also an outlet for homosocial affection, as we also find in the case of Donatello, who, according to spiteful tongues, chose his apprentices for their beauty; or Cellini, who in 1557 was accused of sodomy for being caught with his assistant, Fernando da Montepulciano, ‘in bed as if he were his wife’.

Iconographically speaking, Bronzino’s Saint Sebastian belongs to a devotional type found chiefly in northern and central Italy in which the saint is depicted half-length and naked or wearing a loincloth, interceding for the plague-stricken. It is significant that Florence was ravaged by plague between 1529 and 1530, and there is speculation whether this work may have been commissioned as an expression of gratitude when the outbreak died out.

According to Cox-Rearick, these traditional aspects of the saint’s representation alternate with more novel ones such as the marble-like appearance of the saint’s body, in keeping with the interest in classical statuary at the time, which can be seen in Bronzino’s painting. The well-formed body contrasts with the ephebic, ambiguous and natural-looking face that has something of a portrait about it.

The saint’s naturalness and physical intimacy appear to be related to, and foreshadow, certain ideals upheld by the Council of Trent (1545‒1563), which established saints as intermediaries between men and God. Nevertheless, according to Cox-Rearick, this work goes further as it consciously (and ‘consciously’ should be stressed) represents homoerotic aspects. How can this homoerotic nature be accounted for? It is clear to this scholar that in Bronzino’s image the saint’s role as intercessor is eclipsed by secular and even erotic aspects. ‘The conventual attributes and gestures of Sebastian as intercessor are not present: he wears no halo, his gaze is not directed heavenward to God, and he carries no palm of martyrdom.’ Together with these absences, there is a very significant presence, that of the arrows: ‘The arrows […] are not abstract symbols […] but erotic emblems: one has penetrated his body, the other is casually, but suggestively, held against the pink drapery, the saint’s index finger curved around and almost touching the arrowhead. Furthermore, Sebastian is portrayed in intimate conversation with an observer, gesturing with his right hand to emphasise his words. Finally […] Bronzino’s Sebastian has a portrait-like, androgynous face, which contrasts provocatively with his sculptural torso.’

In Cox-Rearick’s opinion, this Saint Sebastian has an ambiguous, part-religious and part-homoerotic meaning that is established not only by the erotic interpretation that was becoming fashionable in scholarly circles but also by the details of the picture. Particularly significant details are the arrows, which this author compares to those of Cupid in other paintings by Bronzino and which the artist uses as an emblem of the blend of humanistic Christianity and Apollonian classicism that is embodied particularly well by the figure of Saint Sebastian.

Saint Catherine of Alexandria

Caravaggio’s sexuality – which aroused historians’ interest early on – is one of the most controversial issues in art history owing both to the ambiguity of his work and the lack of related documentation.

Given the shortage of first-hand documentary sources, Caravaggio’s paintings and their interpretation are almost all we have to go on for speculating about his sexuality. This poses an interesting challenge, as it is necessary to examine them through the eyes of a seventeenth-century rather than a twenty-first-century spectator.

The myth of Caravaggio as a sexual rebel was built on a very specific corpus of works: those executed in the 1590s, when he arrived in Rome and worked in the service of Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte. The cardinal introduced him to the circles of the most powerful people in the city and provided him with stability. Caravaggio painted one of his best-known works for the cardinal and most likely this Saint Catherine of Alexandria, which is notable for its naturalism and sensuality. The model has been identified as Fillide Melandroni, a famous courtesan of the day.

Cardinal Del Monte was the eyes and ears of the Medicis in Rome, who were traditionally linked to France. Enemies such as the lawyer and historian Ameyden, who was paid by Spain, sullied the cardinal’s reputation in one of the earliest biographies, which conveys an image of him as a corrupt sodomite that eventually found its way into Caravaggio’s work.

According to biographers like Andrew Graham-Dixon, the cardinal was relatively wealthy, open-minded, an art lover and perhaps not very fond of the Counter-Reformation, but certainly not the libertine history makes him out to be. Certain art historians and historians of sexuality like Margaret Walters, James Small, Cristopher Reed and James S. Saslow believe that the works produced for Cardinal Del Monte illustrate a highly novel phenomenon: the growth of cities and their economic structures led to the emergence for the first time of a group of wealthy men interested in producing and sharing a series of homoerotic works that could be interpreted as one of the first examples of homosexual subculture.

Another of Caravaggio’s promotors was Vincenzo Giustiniani, an aristocrat and musical and astrological theoretician, for whom he painted the Lute Player and the controversial Amor Vincit Omnia where Cupid is depicted as an adolescent in all his carnality. Giustiniani kept it in a prominent place but concealed behind a curtain – some claimed out of modesty and others to heighten the drama when it was revealed. This anecdote raises an interesting question about the homoerotic interpretation of Caravaggio’s oeuvre as an exclusively twentieth-century phenomenon, as although a few of his works were censored in his own day, it was because they were considered indecorous from the point of view of faith and not for their connotations of homosexual desire.

The most abundant and reliable sources we have on Caravaggio’s life are legal documents, which have provided a basis for creating an image of him as a violent man – though he did, of course, live in a violent age. As for homosexual practices, Caravaggio ended up filing a lawsuit against his rival and subsequent biographer Giovanni Baglione over one of Baglione’s paintings which featured a demon with Caravaggio’s face beside a naked youth – a visual accusation of sodomy that was a direct reference to Caravaggio’s Amor Vincit Omnia. Caravaggio reacted by writing satirical poems and the matter ended up in court, where snippets of information about his private life were revealed: for example, a certain G. Battista was said to be Caravaggio’s bardassa. The term bardassa is frequently found in Florentine legal literature and refers to a young man who offers sexual services to other men as a receiving partner – that is, a prostitute; indeed, the court papers mention that Caravaggio shared these expenses with a friend.

Another name that is linked to Caravaggio is Cecco. Called Cecco de Caravaggio, he was the painter’s assistant and apprentice. Cecco has gone down in art history for having posed for the famous Cupid and for many other paintings by the master, with whom, according to an inventory of the painter’s possessions, he shared a room and enjoyed a long personal and professional relationship.

Other legal documents reveal that Caravaggio was involved in disputes with women and regularly hung out in brothels. However, his fondness for young men soon surfaced in Messina, a city where his paintings were greatly appreciated. He was forced to flee after attacking a teacher who questioned his habit of spending the afternoons with his pupils, according to Francesco Susinno, a priest, painter and biographer of local painters. Andrew GrahamDixon, the author of one of the most recent biographies of Caravaggio, lends credence to the story.

Graham-Dixon, who sets out to debunk the myth of Caravaggio as a gay countercultural figure, sums up his sexuality as follows:

Caravaggio was capable of being aroused by the physical presence of other men. He could not have painted such figures in the way that he did if that were not so. But he was equally attracted to women, as certain other painting from the late 1590s, such as the transfixing St Catherine of Alexandria, plainly demonstrate. Insofar as the art reveals the man, Caravaggio’s painting suggests and ambiguous sexual personality.

San Sebastian

Figures like Saint Sebastian, although depicted half-naked and imbued with sexuality and physical potency, were produced in a completely different context to their Renaissance counterparts. The Counter-Reformation redefined both the images and the functions of saints. In a period in which outbreaks of the plague were less frequent and Christian images were designed to be, above all, educational, Saint Sebastian became a model of martyrdom and Christian death. In his depictions, eros thus gave way to agape: unconditional, reflexive and sacrificial love of God.

The patron who commissioned this work, Cardinal Maffeo Barberini, turned to psalm 42 in his poem In Imaginis Sancti Sebastiani to explain unlimited love and absolute devotion to God: ‘As a hart longs for flowing streams, so longs my soul for thee, O God.’ The offering to God thus predominates over the sensuality of the figure – a sensuality viewed from our contemporary gaze, which is tainted by the treatment given to the male body in advertising since the 1980s. We cannot help interpreting it erotically because of the visual poetry we find in the pose.

We should point out that the history of the Barberini family is intrinsically linked to that of Saint Sebastian, as the family chapel was built on the spot where the martyr’s body was found. They made him their patron saint and assembled and commissioned many images of him.

There is another aspect of this work that cannot be considered of minor importance: it was the first commission the Barberini family gave to a young Bernini and marked the start of what would be a prosperous working relationship that changed the appearance of Rome forever when Maffeo Barberini became the powerful Urban VIII and Bernini one of his chief architects. The lawyer and historian Teodoro Ameyden stated of Urban VIII that he ‘wished to appear more like a prince than a pope’ and pointed out his lax attitude to the homosexual practices of some of his prominent men – such as Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte, Caravaggio’s protector – though as a pope he encouraged anonymous reporting to the Roman Inquisition.

Although Bernini was famous for his many mistresses, various documents attest to the shadow of sodomy that hovered over him. For example, there was his connection with Pope Paul V’s nephew Cardinal Scipione Borghese, a patron of the arts who was known for his fondness for beautiful young men; Bernini made two well-known busts of him in 1632 and the cardinal promoted him in Rome. Then there was the episode involving his own brother and right-hand man, Luigi Bernini, whose expertise as an engineer contributed to the flourishing of his own art. Luigi was reported in 1670 for forcing a boy, a cardinal’s nephew, to have sexual intercourse. He fled to Naples to avoid the death penalty, which was finally revoked thanks to Gian Lorenzo’s friends in high places.

Although Roman society was scandalised and Gian Lorenzo, whose influence was beginning to wane, had to return the favours in the form of artworks, the history of his brother Luigi went down in the legal annals of a city where 144 cases of sodomy were tried between 1601 and 1666.

Nevertheless, in keeping with the authorities’ vagueness about homosexual conduct, the Acta Santorum or Acts of the Saints, the most important seventeenth-century compilation of saints’ lives, establishes an ambiguous relationship between Sebastian and his superiors, stating that ‘he was loved by emperors Diocletian and Maximilian’. This led certain subsequent hagiographers to describe him as ‘the emperor’s favourite’ – an expression with homoerotic connotations which added a further layer of meaning to which great significance was given from the nineteenth century onwards.

According to Richard A. Kaye in his study of how Saint Sebastian became a gay icon, in the nineteenth century the saint took on a new quality: depravity. While leading Victorian religious thinkers attempted to masculinise the saint, an army of decadent artists were eager to turn him into an icon of vice and corruption. Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, Oscar Wilde and Aubrey Beardsley emphasised his dissolute elegance and sultry sensuality and created a certain aesthetic of the ‘sublime homosexual’ with his arrows and sinuous pose. In Kaye’s opinion, this transformation of the saint symbolised a transformation in the discourses on homosexuality itself: it went from being regarded primarily as a sin and, accordingly, belonging to the religious sphere, to being considered an illness and, therefore, belonging to the field of medicine. However, the nineteenth century ended with another type of discourse: legal – the sodomy conviction of Oscar Wilde, who went by the name of ‘Sebastian Melmoth’ in his Parisian exile.

Reminiscences of decadence lingered on in the first decade of the twentieth century and the homosexual desire that was taking root in public awareness could only be expressed in ‘highly coded’ language. Perhaps Aschenbach, the main character in the novel Death in Venice, makes such a more or less secret nod when he describes the saint as a ‘new type of hero’.

Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis and its popularisation further strengthened the saint’s connection with homosexuality: the welcoming and even joyful attitude with which the saint receives the arrows was explained as a desire for penetration and seen to embody the sadomasochistic or narcissistic aspects of the myth.

The twentieth century celebrated another aspect of the depictions of the saint: his kitsch aesthetic, with tawdry symbols of desire, punishment and sadomasochism that stand out in artistic productions such as Tennessee Williams’s play Suddenly Last Summer, where Sebastian is cast as a young poet who propositions boys on the Italian beaches until he is martyred for doing so.

Although he had started to become ‘old-fashioned’ following the emergence of the LGBT rights movement, Sebastian regained his former prominence as a result of the AIDS pandemic in the 1980s, recovering his association with epidemics.

Throughout the twentieth century, Saint Sebastian stood apart from other homosexual myths like Hadrian and Antinous, Corydon and Alexis, Damon and Pythias, Theseus and Pirithous, Zeus and Ganymede, and David and Jonathan in that his story is not one of a shared passion but one of individual martyrdom: a martyrdom caused by a confession – that of his faith. This aspect links up with how homosexuality is viewed today, not as something immoral or punishable but as an act of reasserting one’s identity.

David With the Head of Goliath and Two Soldiers

The story of David includes a number of episodes that hint at love relationships with other men.

Such as when he met Johnathan, King Saul’s eldest son, who became his close friend. According to the biblical texts, when mourning Jonathan’s death David exclaims, "Your love to me was wonderful, surpassing the love of women".

This painter of French origin imagines the young David to be good-looking and elated, according to the description given in the first book of Samuel: ‘He was glowing with health and had a fine appearance and handsome features.’ The Old Testament passage tells how the future king of Israel toppled Goliath with a sling before cutting off his head with his own sword, which he grips here in his left hand, while the blood continues to trickle out, much to the bewilderment of two soldiers. The fingers of his right hand are sensually entwined in the Philistine’s locks in a sort of caress that contrasts with the act he has just committed.

David cuts a majestic figure with his intense gaze and vigorous pose, his marble-like body leaning over the table on the sole remains of Goliath’s body, reinforcing his power and victory with this bodily gesture. But his appearance is not that of a man of great physical strength capable of slaying a giant; instead, his youth, pale skin and face with fleshy lips, pale eyes and soft, shiny hair convey an androgynous image. In addition, his shepherd’s clothing reveals much of his torso, whose skin irradiates light.

The Death of Hyacinthus

Myths, which are regarded as timeless or eternal stories, have been used over the centuries to explain, illustrate or account for a great variety of themes: from political power to same-sex attraction, as we find in this picture where the love story of Apollo and Hyacinthus is set in the eighteenth century. Let us briefly recall the story: like Adonis and Ganymede, Hyacinthus was a young and beautiful mortal who enamoured gods. In this case it was Apollo who was captivated by Hyacinthus, whom he accidently killed with a discus that was deflected by Zepyrus, the god of the west wind who, according to some versions, was also in love with the boy. According to the story, reddish hyacinths sprang from his spilt blood.

This eternal story is updated here by the Venetian painter Giambattista Tiepolo, who replaces Apollo’s discus with a tennis racquet and ball – a reference to pallacorda, a version of the game that had been all the rage at the courts since the mid-sixteenth century. The picture was designed by the artist and his client, Baron Wilhelm Friedrich Schaumburg Lippe Bückeburg, as a tribute to love between two men. In 1752 the baron, who was 28 at the time, was living in Venice to complete his humanistic grounding as part of the Grand Tour.

We know from surviving letters that the baron was romantically involved with a young Hungarian, but later left him to go and live with a Spanish musician in Venice, whom his father, the elderly baron, called ‘your friend Apollo’. Tiepolo specialists like Keith Christiansen point out that the death of the Spanish musician in 1751 was fundamental to the genesis of the painting.

The Grand Tour was a trip to southern Europe, chiefly Italy, designed as a rite of passage to maturity for young upperclass men of northern Europe in the eighteenth century. It usually lasted a couple of years and allowed young men – intellectuals, artists and nobles, always accompanied by a tutor – to further their education through first-hand contact with the classical sources. It also provided plenty of opportunities to meet people, enjoy the milder climate, buy antiques and become initiated into sex, be it with men or women. According to Jeremy Black in his book on the Grand Tour, in countries like England and Germany and in the upper echelons of society – where marriage had a powerful economic component and was governed by strict rules – these trips were considered to entail considerable freedoms and risks. One of the main hazards was homosexuality, which in England was held to be a foreign vice originating in the Mediterranean, especially Italy, as explained in the treatise of the day Plain Reasons for the Growth of Sodomy. Venice in particular was considered by some to be ‘the brothel of Europe’. Back in their countries of origin, these connoisseurs established their own clubs for studying antiquities or followed their own fashions imbued with certain homosexual connotations, such as those of the so-called ‘macaronis’, the forerunners of dandies with their effeminate artifices.

The degree of sexual freedom in this painting is, however, fairly unusual. For several decades of the eighteenth century – paradoxically called the Age of Enlightenment – hysteria about sodomy reached a height in northern European countries, which were particularly prone to moralising owing to the tensions inherited from the Reformation and Counter-Reformation.

Furthermore, the very political tensions that did away with Grand Tours – that is, the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars – led to the decriminalisation of sodomy: in 1785 the reformist Condorcet, but also Montesquieu, Voltaire and Jeremy Bentham, proposed abolishing the punishments, and this proposal was legally adopted in France in 1791. The Napoleonic penal code, which maintained the abolition, spread across Europe after its enactment in 1810.

Boy in a Turban holding a Nosegay

Borrowing a phrase from Oscar Wilde, we might sum up this painting as ‘beauty that dares not speak its name’. There are undoubtedly certain elements in this work, certain clues, that do not go unnoticed to an eye accustomed to searching for cultural references: the androgyny of the sitter, the sensuality of the oriental robes and the bouquet of flowers he holds, which can be interpreted as a sexual invitation but, above all, the profound silence that emanates from it.

It is a fitting silence, because there is no documentary evidence whatsoever to associate either the sitter or the painter with homosexuality, although leading specialists on Michiel Sweerts’s oeuvre such as Thomas Röske and Albert Blankert speak of an ill-concealed homoeroticism in his works, especially those on wrestling themes.

Certainly, Sweerts’s life was not short of mystery or intriguing episodes. Born in Brussels in 1624 to a rich Flemish merchant, he was christened and raised as a Catholic, and the earliest known reference to him as an artist cites him as being in Rome in 1646 to study classical art. There, always guided by a marked individuality, he kept a reasonable distance from the Academy and its subjects and techniques as well as from the group of northern European expats, the so-called bentvueghels (bamboccianti) who portrayed street scenes and folk types. And so, combining classicism and anecdote, he ended up producing an art that stood out in a city full of talent – Bernini, Borromini, Velázquez and Lorrain were living there at the time – and was taken under the wing of Pope Innocent X, who made Sweerts a cavalière.

In 1656 he returned to Belgium, which was still resonating with the execution of the famous sculptor Jerôme Duquesnoy the Younger, convicted of practicing sodomy with his young models. According to Claude J. Summers, the execution may have been a warning to the community of artists entrusted with creating Counter-Reformation art to avoid engaging in improper conduct. Around this time Sweerts converted to a more fervent immersion in his faith and decided to embark on a voyage to China as a missionary. After leaving the expedition in Turkey, he made his own way to the coasts of Goa (now an Indian state), at which point his life again becomes shrouded in mystery until his death in 1664.

Speaking of Rubens, the scholar Daniela Hammer-Tugendhat has pointed out that art history established a pattern whereby the man is the artist and possesses the gaze, and the woman is the erotic object of his gaze; this, especially from the sixteenth century onwards, led to the disappearance of works portraying men erotically. Although male nudes were not unusual in Catholic countries – we find them, for example, in biblical allegories or history paintings – Sweerts’ bathers and wrestlers are certainly so striking for their sensuality devoid of any message that they have led different generations of historians to speculate about the artist’s possible homosexuality.

Horsewoman, Full-Face (L'Amazone)

Édouard Manet was one of the first artists who realised that the world was changing and that these changes were spreading from major cities to the rest of society. He thus steeped everyday experiences in the big city in the grandeur that art had previously reserved for the great heroic stories of the past. Like Charles Baudelaire, he was convinced that "the true painter will be the one who is able to wrest the epic side from contemporary life".

Modern life was embodied by new relationships, new places and new ways of looking at things and of being seen. Both men viewed fashion as a key feature of this modernity.

Horsewoman, Full-Face belongs to an unfinished series on the four seasons that Manet painted in the last two years of his life. In all the works in the series, the artist pays great attention to the clothing worn by the subjects, real women, depicting various items of the latest female fashions to represent each season of the year. The Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza picture represents summer, and in it the young Henriette Chabot sports a dark riding dress. Beginning in the eighteenth century, horsewomen symbolised modern women, emancipated and independent, and it should be remembered that female clothing was also inspired by male dress.

The image of this horsewoman thus reflects a change in the world of women, whose most intimate environment was also praised by Baudelaire in a new idea of lesbian modernity. He was the main disseminator of the word ‘lesbian’ to refer to homosexual women in nineteenth-century France. The term is derived from the island of Lesbos, in Greece, where the poetess Sappho, who was known for her writings about love between women, lived more than 2,500 years ago.

A few lines from ‘Lesbos’, one of the poems in Baudelaire’s Flowers of Evil, give an idea of this context:

[…]What boot the laws of just and of unjust? Great-hearted virgins, honour of the isles, Lo, your religion also is august, And love at hell and heaven together smiles! What boot the laws of just and of unjust?

For Lesbos chose me out from all my peers. To sing the secret of her maids in flower. Opening the mystery dark from childhood’s hour Of frantic laughters, mix’d with sombre tears; For Lesbos chose me out from all my peers.

[…]Of Sappho, who, blaspheming, died that day When trampling on the rite and sacred creed. She made her body fair the supreme prey Of one whose pride punish’d the impious deed Of Sappho who, blaspheming, died that day.

[…]Meanwhile, in the United Kingdom, the other European hub of modernity, Victorian double standards dominated social conduct. An example of this duality can be found in one of the great literary works of the period, Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest, which is full of double-entendres that explore the concept of the double life to which so many homosexuals were accustomed. Oscar Wilde is also an excellent example of how these double standards could be laid bare by the trials to which he was subjected.

The trials of Oscar Wilde (1895) are important for many reasons, among them because they laid some of the first foundations for a way of feeling, thinking and reflecting on contemporary homosexuality which was disseminated by the press and reached many sectors of the population. Secondly, because this reflection took place in the context of a persecution that produced a lay martyr who defended, in Wilde’s words, ‘the love that dare not speak its name’. Thirdly, because the government used the huge social scandal to its own advantage to make homophobia and the persecution of homosexuality a means of increasing their popularity – something which, unfortunately, was common in the century that was then beginning.

Continued on the ground floor

On the map you can see the rooms where the masterworks are located.

Portrait of Millicent, Duchess of Sutherland

A privileged witness to all this was the painter John Singer Sargent, who became the most successful portraitist of his day and whose cosmopolitan but solitary bachelor’s lifestyle is currently being analysed from a new perspective: that of his extensive network of friends, his drawings of male nudes and his secrecy about his personal life, which led his family to burn his personal papers after his death (but not his large collection of drawings of male nudes) so that the only documents we have are his artworks.

Keenly aware of his role in public life and the envy he aroused, Singer Sargent led a very hermetic life save for a few carefully calculated artistic scandals for publicity purposes. He likewise turned down the invitation to be a regular contributor to one of the bibles of decadence, The Yellow Book, but concealed his friendships with famous scandal-mongers and dandies of the day such as Oscar Wilde, Henry James and Robert de Montesquieu.

In keeping with these contradictions, his personal universe was marked by the domestic realm (he enjoyed the company of his sisters and nieces for long periods) and by cosmopolitan scene, with constant travels during which he alternated flirtations with high society ladies with profound friendships with men. Particularly notable is his long 25-year relationship with his butler, Nicola D’Iverno.

The supposed double life led by Sargent and other contemporaries such as Oscar Wilde in fact resembled the novel written by another of the painter’s great friends, Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson. The novel, which has been viewed as a reflection of Victorian double standards and an example of the period’s terror of homosexuality, shows the tension triggered by the growing visibility of homosexuality during the nineteenth century. This tension culminated in a series of scandals of which the trials of Oscar Wilde were merely the climax.

The paths of Sargent and the Duchess of Sutherland crossed in this turn-of-thecentury London. He was one of the most prestigious portraitists of the period and the favourite of the elites; she was one of the most celebrated and influential ladies of the time. The duchess, a model of intelligence and elegance, was known as a writer but also for her keen social awareness.

The painter had a gift for capturing his sitters’ psychological traits and depicted her with a poise that combined her aristocratic bearing with her progressive and independent character expressed in a lively gaze directed at the spectator. He thus achieved a portrait packed with personality but did not omit the symbols of the lady’s rank. The references to classical culture showed that Lady Millicent possessed a delicate and distinguished taste that set her apart from the bourgeoisie, who preferred Art Nouveau. In addition, Sargent presented himself as the continuer of the great English portraiture tradition of the previous century, in which noblewomen were depicted as classical goddesses.

The key to Sargent’s sexuality remains concealed in his works, especially his private watercolours and drawings; many were spontaneously produced and were not exhibited for several decades. Prominent among them all for its striking sexuality is that of the bellhop Thomas E. McKeller. In addition to these personal works, there are 29 charcoal drawings preparatory for a large mural for Boston’s public library entitled The Triumph of Religion. They feature drawings of naked men in sensual poses.

Documentary sources provide no clues about Sargent’s sexuality: whether it was marked by homoerotic impulses or whether his drawings of male nudes, the only ‘proof’ of his interests, stemmed from other cultural factors. Nor do we know whether, out of respectability, he concealed his lovers, be they men or women, or whether he adopted the guise of an asexual dandy that was culturally acceptable for a bachelor. Repressed or simply reserved, Sargent is a good example of how the influence of certain questions about historical figures can provide a richer and more diverse image of the figure of the artist, especially at a time when modern homosexuality had not yet been defined and had neither a name nor characteristic cultural traits.

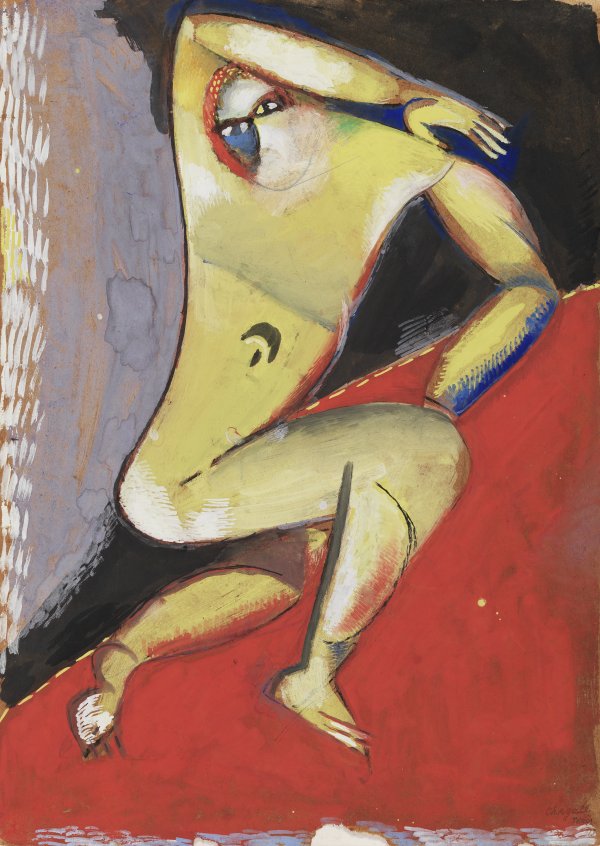

Nude

Marc Chagall produced nude in 1913 during his first stay in Paris. He had arrived in 1911 and was soon captivated by the frenzied pace of life in the capital and decided to stay for three years. In addition to the major advances made in painting and sculpture, a new art form was emerging and truly transforming Paris and its cultural offering: the Ballets Russes, whose first season in Paris was in 1909. The company, which revolutionised the performing arts, brought to ballet the avant-garde trends and the desire to experiment with new aesthetic and expressive forms.

Chagall was doubly in contact with the world of the Ballets Russes: firstly, his mentor had designed sets for Sergei Diaghilev, founder of the Ballets, and had secured major successes for productions such as Cleopatra; and secondly, Chagall himself had had the chance to meet Vaslav Nijinsky, the company’s star male dancer, at the Zvantseva art school in St Petersburg. This combination of circumstances has led scholars to believe that the figure of the Nude, with his extreme, dislocated posture, may represent Nijinsky in an image alluding to the decisive contributions he made to dance by flouting the strict rules of the academy.

Nijinsky joined the Ballets Russes in 1909, encouraged by its founder, and became his lover until 1913, when he married the Hungarian countess and dancer Romola de Pulszky. Their life histories were plagued with turbulent episodes. We know from her sister’s memoirs that the countess had to use all kinds of wiles to lure Nijinsky into marrying her, seducing him with her powerful contacts and her fortune. When they married, Diaghilev, in a fit of jealousy, dismissed Nijinsky, whose career had already suffered many ups and downs.

Nijinsky was always a deeply transgressive and controversial figure, openly homosexual and with an emotional intensity that he brilliantly expressed in his dynamic and always scandalous choreographies. They exuded a sexual energy that often verged on violence, consciously and genuinely seeking a contrast with the fluidity of contemporary French ballet and causing a stir every time they were premiered.

In 1912, when he performed Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun with his own choreography and music by Claude Debussy, his movements earned him fierce criticism from Le Figaro, which questioned the ‘morality’ of his performance. The First World War took the couple by surprise in Austria, and Nijinsky, as a Russian, was imprisoned first in Budapest and later in Vienna. Despite the enmity of the former lovers, Diaghilev used his contacts to have the dancer released, and took him back into the company. However, the experience of captivity, coupled with an inherited tendency towards schizophrenia, had taken their toll on Nijinsky. He became increasingly more paranoid and began suffering from persecutory manias that forced him to abandon his dancing career and be interned in various sanatoriums. He spent the rest of his life in psychiatric hospitals and asylums until he died in 1950.

Love, Love, Love. Homage to Gertrude Stein

This painting is part of a group of poster portraits of prominent figures from the cultural scene which Charles Demuth created between 1924 and 1928.

They are symbolic portraits as he does not portray the sitters’ physical appearance but constructs their identities through words and objects that involve a sort of visual guessing game and supposedly speak of the subjects’ personality and tastes. With this approach to portraiture he called into question the notion of likeness as an essential aim of the genre, as well as challenging the complex and controversial issue of identity.

The person portrayed here is Gertrude Stein, an American writer who spent most of her life in France. She pioneered modernist literature, through which she herself had cultivated symbolic portraits of this kind, and was also well known for her important work as a collector of modern art at the time this portrait was produced.

The word "LOVE", repeated three times, could be related to her fondness for the number three in her writings. Stein is the author of one of the first stories of a love affair between women, the autobiographical Q.E.D. The work contains an encoded message that the spectator must interpret – perhaps this explains the mask, an element whose meaning in this work still remains concealed.

Charles Demuth, like her, was an American who was part of the free Paris scene of the early twentieth century. Today he is hailed as one of the first artists to openly exhibit his sexual orientation through his works.

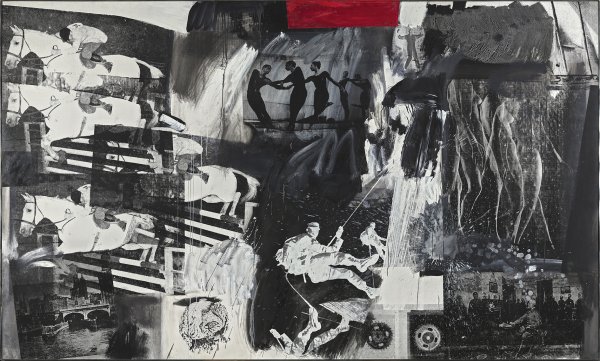

Express

Express belongs to a series of silkscreen prints Robert Rauschenberg made between 1962 and 1963. Rauschenberg was attracted to silkscreen printmaking because it enabled him to print images on a screen on a different scale to the original one.

He then transferred them to canvas, exploring their expressive possibilities by arranging and combining them with thick, vigorous strokes of paint. This experimentation allowed him to reconcile abstract expressionism and figuration in an innovative way.

Sometimes he used photographs of his own, other times he used cuttings from magazines or other mass media. When we view Express, we perceive the multiple spaces and the dispersion of the various points of interest in the work; our perception of them is simultaneous, random, fragmented and very fast, and this also evokes the idea of speed contained in the title.

To choose themes he combined personal interests, historical events and elements of his private life, converting the works into a sort of time capsule that is both particular and universal.

But the personal references were complex and never explicit, especially if they were related to a homosexuality that he never revealed publicly. They were recognisable only to those who knew him very well or were very familiar with homosexual culture. Rauschenberg produced this work two years after his breakup with the artist Jasper Johns. For both men the time they spent together was personally and professionally meaningful, though neither ever spoke clearly about the most intimate side of their relationship.

In this connection, we should not forget the witch hunt that took place in the United States in the 1950s against the communists, who were accused of being disloyal to the nation, though it ended up with more convictions of homosexuals.

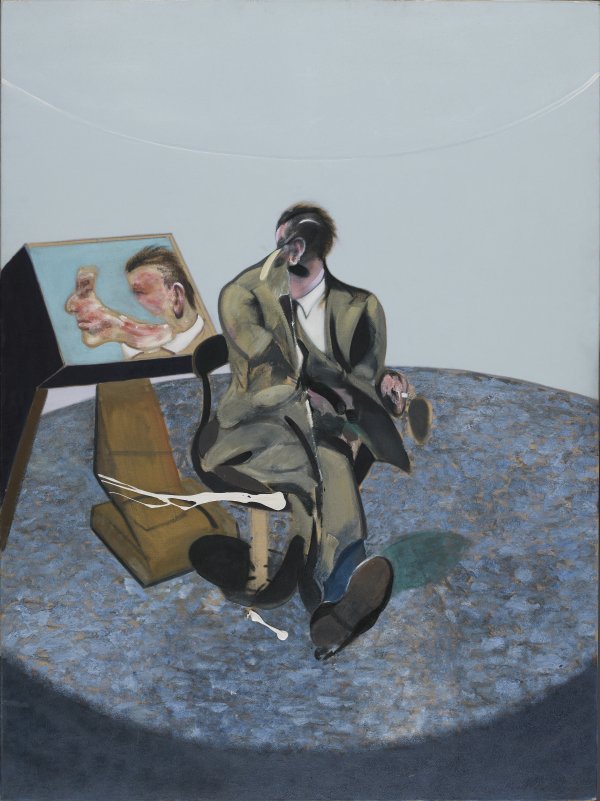

Portrait of George Dyer in a Mirror

Francis Bacon was born in Dublin in 1909 to British parents. According to the artist, his fascination with violence stemmed from the Irish civil war. His childhood was marked by a complicated relationship with his parents – especially his father, who rejected his son’s homosexuality, which was evident at a very early age.

In 1925 he went to live in Berlin, where a family friend was to take him in hand and, according to his father’s expectations, ‘make a man of him’. These hopes could not have been dashed more ironically, as Bacon’s father had unknowingly sent his son to the hub of sexual freedom in Europe, the Berlin of the Golden Twenties. The German capital was then the epicentre of modernity on the Old Continent, a place where magazines featuring male nudes had been published and gay films had been screened since the beginning of the century. In a sense, homosexuality was chic and trendy in a city that was a refuge for all those whom strait-laced Europe still rejected during the interwar years.

In 1927 Bacon went to Paris, where he became familiar with the art of Picasso and changed his vocation from furniture designer to painter. After spending a few months in Paris, he headed for London, where he met the much older artist Roy de Maistre and moved in with him, becoming his lover and apprentice. In London he started out as a painter, chiefly producing watercolours but yet to find his own style until one day, the sight of the meat counter in Harrods planted the seed of his aesthetic ambitions. This is how Bacon came to develop an interest in subjects that enabled him to twist and disfigure human flesh, come face to face with it, and transmit the reality of the image in its most harrowing state.

Around this time he established a relationship pattern that would continue throughout his lifetime. He usually became involved with older men in highly toxic power relationships whose dramatic component is powerfully expressed in the many portraits he painted of his lovers. Bacon confessed to his biographer Michael Peppiatt that Peter Lacy, an alcoholic pianist, was the love of his life. However, their relationship was characterised by violent fights, beatings and jealousy.

After Lacy died, Bacon met George Dyer when the latter broke into his studio. Dyer was a practically illiterate burglar who became Bacon’s first younger and less experienced lover. This granted Bacon a certain amount of power in the relationship that led him to take on an almost fatherly role. Dyer abandoned crime but soon sank into alcoholism and his erratic behaviour caused Bacon’s cronies to consider him a nuisance. Dyer was a danger to Bacon’s reputation as the artist, as he himself stated, despite giving free rein to his impulses in his work, had been careful about his public image in an essentially puritanical and homophobic society.

Dyer’s addiction drove him to commit suicide in 1971. His death came as a very harsh blow to the artist, whose feelings for his lover were sincere, despite their stormy relationship. During the following three years Bacon portrayed him regularly, even depicting the moment after his death in the so-called ‘black triptychs’. In George Dyer in a Mirror we find features common to Bacon’s portraits. The figure is deformed, but by no means gratuitously. Bacon himself stated, "I do not distort for the pleasure of distorting; my figures are not subjected to torture, I try to convey the reality of an image in its most agonising moment".

Andrew Dombrowski reflects on a curious detail in this work in the related entry for the Encyclopedia of Gay Histories and Cultures. The splash of oil paint level with Dyer’s groin can be interpreted in several ways: it could be a protest against naturalist art, which focuses on faithfully reproducing physical reality, or an allegory of the author’s signature; or, given its position, it could also be considered an allusion to ejaculation and, therefore, to the eminently sexual nature of the couple’s relationship.

The reams written about Bacon’s love life and published after his death reveal the deep-seated conflict the artist wrestled with throughout his life: striving to create an authentic art that came from within and was preferably autobiographical, but at the same time attempting to maintain a social identity that was acceptable to the artistic and bourgeois circles he needed to frequent as a respected artist who wished to earn a living with his work.

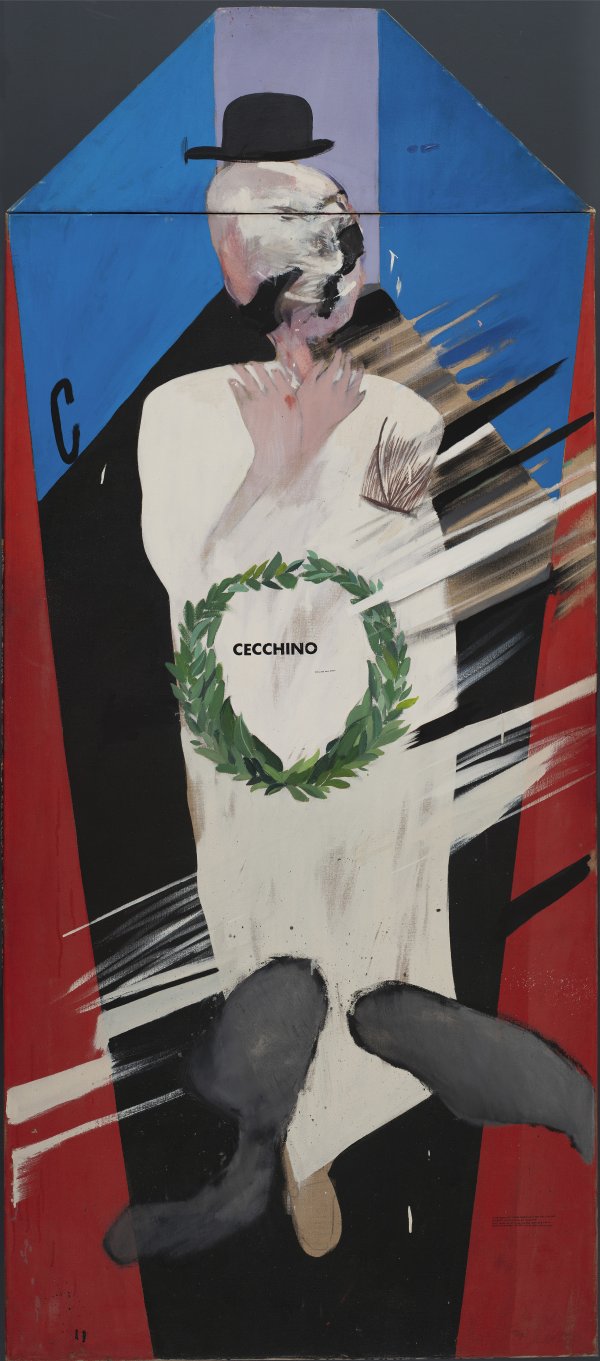

In Memoriam of Cecchino Bracci

David Hockney is one of the most influential British artists in history, a distinguished practitioner of a brand of pop art that draws chiefly on purely autobiographical elements, shunning the idea cultivated by Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein of art as a reflection of mass culture.

Although aware of his homosexuality from a very early age, Hockney chose to keep quiet about it during his artistic training and until he enrolled at the Royal College of Art in London, when his work began to reveal his sexuality through the chosen themes. This tendency continued throughout his entire career, with allusions that were explicit or veiled in varying degrees.

His Love Paintings display the aesthetic influence of gay magazines featuring nude boys engaging in everyday activities such as mowing the lawn or sunbathing. These images, set in an idyllic landscape of the west coast of the USA, planted the seed of Hockney’s curiosity about California, where he ended up living.

As well as drawing inspiration for art from his own sexual orientation – which might be considered an assertion of homosexuality per se – Hockney was an important activist against Margaret Thatcher’s repressive policies towards the LGBT community.

In this work, In Memoriam of Cecchino Bracci, Hockney draws on an episode from the life of Michelangelo to evoke the homoerotic tradition of classical Greece and Renaissance Italy. The height of beauty is the athletic, virile body reproduced in sculptures and frescoes and Michelangelo was the greatest exponent of this cult of virility in art. He even succeeded in incorporating naked male bodies into religious scenes, such as the 20 ignudi (nudes) on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, whose presence displeased many popes.

The consideration of virility and masculinity as the most appreciated social and aesthetic values entails a misogyny that is highly prevalent in what is even today regarded as ‘progressive’ humanism. The efforts of this school of thought were always centred on highlighting male virtues, never those of women.

According to Michelangelo’s biographer Ascanio Condivi, the artist spoke solely in male terms when he referred to love and displayed a preference for the boys who were entrusted to him as apprentices or models, with whom he established a power relationship governed by clear-cut rules that was fairly common in the Italian art world. The master provided them with a comfortable lifestyle in exchange for their attentions. Even the parents who entrusted their sons to the artist were aware of this.

Such is the case of the young Cecchino Bracci, the nephew of Luigi del Riccio, a Florentine nobleman who was acquainted with Michelangelo. Cecchino was a very beautiful adolescent who had captivated the artist, and his premature death deeply affected him.

Aware of Michelangelo’s affection for his nephew, Del Riccio commissioned the artist to design his tomb for Santa Maria in Aracoeli, in Rome, and to write a series of epitaphs.

Saddened by the memory of Cecchino, with whom he had been sexually involved, Michelangelo composed 50 epitaphs in his honour, making a direct allusion to the physical consummation of their love. He later wrote to Del Riccio to ensure that the epitaphs would not be publicly displayed without his consent and without being duly corrected, but when Del Riccio told the artist he intended to publish them without any alterations, Michelangelo asked him to destroy the texts.

Although Del Riccio eventually yielded to his request, their friendship ended as a result of the quarrel.

Hockney depicts the young man inside his coffin, wrapped in a shroud, his arms crossed over his chest. Above his body a laurel wreath encircles the word ‘cecchino’ and, lower right, in tiny lettering, are the first lines of one of Michelangelo’s epitaphs praising the youth’s beauty:

If buried here those beautiful eyes are closed forever. This is now my requiem: They were alive and no one noticed them. Now everybody weeps them dead and lost.

Smyrna Greek (Nikos)

Here we see a self-engrossed man wandering around a gloomy-looking area, ignoring the prostitute who approaches him. It is a portrait with deep symbolic undertones, as it merges two people who lived very far apart in time but are connected through the work of one of them. The figure has the physical features of the London-based Greek poet and publisher Nikos Stangos, but the spirit is that of the poet Constantine Cavafy during one of his strolls around the port of Alexandria, a place for encounters with men which he often mentions in his poems.

Both men cultivated poetry, were of Greek origin and homosexual. Cavafy was the great artist, one of the finest twentieth-century poets, and Stangos published excellent English translations of his work. The painter Kitaj thus creates a fictional world by constructing a character from known and imagined facts, combining his friend Stangos’s features with the essence of the famous poet.

Cavafy was an exemplary employee who led a double life: he worked as a bureaucrat for the Ministry of Public Works during the day, and at night he hung around in taverns, seedy cafés and bars where it was easy to find male lovers. According to Mario Vargas Llosa in his prologue to Cavafy’s homoerotic poems, some of these places usually described in the poems still exist in Alexandria and are still gay hangouts.

Once he came to terms with his homosexuality, Cavafy began to lead a double life like a sort of prism with many sides, some visible and others concealed, depending on the requirements of the context. It may be deduced from his poems that he was somewhat reluctant to perpetuate this double life that made him so uneasy, but the reality of Cavafys’s nocturnal desire almost prevailed over his daytime intentions. According to Timos Málanos in The Poet C P Cavafy, his sexual tendencies caused him long periods of anguish, which was only assuaged by visits to brothels for bisexuals and the odd affaire in the Attarine neighbourhood, which he visited with a servant who kept a lookout for relatives or acquaintances.

The most interesting feature of Cavafy’s oeuvre is his recognition of his source of inspiration: his sensual life. Although he did not write only about this aspect, it can be inferred from the poems that this is from where his art did indeed stem.

Cavafy never wished to publish a book of his poems – not only because of his homosexuality, which had led to his dismissal and social disgrace, but also because it was linked to his taste for the clandestine, the unusual and the inaccessible. Proof of this is the fact that the poems that he did have printed, not all on homosexual desire, were handed out discriminately on separate flysheets to ensure that they only reached the people the poet considered sufficiently intelligent, sensitive or well-read to understand them. As well as the flysheets, two booklets were also printed and distributed in the same way: one containing 12 poems in 1904, and a second in 1910 with 27.

Hercules at the Court of Omphale

Hercules. The theme of Hercules at the court of Omphale is perhaps one of the best-known descriptions of cross-dressing in antiquity and refers to an episode in Hercules’s life when, in a fit of madness, he slays Iphitos and is sentenced by the Oracle of Delphi to serve as a slave for three years.

Hercules performs this task under the orders of Omphale, queen of Lydia, in a captivity described by Ovid as follows in his Letters of Heroines using Hercules’s wife, Deianira as a mouthpiece:

“Doesn’t it cause you shame to restrain those strong arms with gold / And to put jewels upon those solid muscles? [...] / To wear a Maeonian girdle in the manner of a wanton girl / Do you not think this is unfitting? [...] / Antaeus would drag the bands from that hard neck / Lest it disgust him to surrender to an effeminate hero.”

And so, while Hercules dressed in women’s clothing and wove baskets, Omphale bore the hero’s characteristic attributes: the lion’s skin, mace and bow. She also enjoyed his sexual potency: as the scholar Robert Bell points out, Omphale bought Hercules as a sexual object and not as a servant, and after becoming her lover he fathered her four children as well as making a slave girl pregnant.

Homosexuality is not alien to either the Greek or the Roman version of the tradition of Hercules. The reason why Hercules dons the saffron tunic meant for women is something that, according to the scholar Nicole Leroux, anthropologists have attempted to explain from many viewpoints. Some have linked it to the homosexuality inherent in Greek tradition, taking it to be connected with pederasty in pupil-teacher relations and, therefore, a far cry from the feminisation of Hercules, which would have been a contribution of Roman tradition. Others relate Hercules to the rite of marriage, where the exchange of gifts, including tunics, was institutionalised in a tradition that is referred to in Petrarch’s poetry and was used, for example, in the decoration of the Ducal Palace of Urbino to celebrate the marriage of Federico de Montefeltro and Battista Sforza in 1440. Finally, Nicole Leroux links this aspect to Hercules’s relationship with the effeminate Dionysius. In Dionysian celebrations women abandoned their looms and went hunting in the woodlands, while men dressed in women’s clothing. The custom of cross-dressing linked to Dionysian festivities continued until being banned in 692.

In the seventeenth century, the moral climate of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation cloaked the sexuality of artists of the previous century and those of the period in a silence that was broken only by scandalous trials. This phenomenon was illustrated by the censored publication of Michelangelo’s sonnets and Shakespeare’s poems, the biased translations of the poems of Sappho, and the watered-down versions of great myths such as the rape of Ganymede and Monteverdi’s Orpheus, which leaves out the hero’s conversion to homosexuality found in earlier versions.

Nineteenth century. The transition from the nineteenth to the twentieth century was a fascinating time in the history of sexualities. Fin-de-siècle decadence went hand-in-hand with Victorian double standards and was fuelled by the expansion of cities in a period of recent European history known as the Belle Époque in France and as the Edwardian era in England, where an economic and cultural elite were creating a new world.

The Belle Époque, which spanned from the end of the Franco-Prussian war in 1871 to the outbreak of the First World War, marked a zenith in culture in general and in homosexual culture in particular in the French capital. Paris was then the world epicentre of culture, home to intellectuals and an unrivalled centre for artistic experimentation. What is more, according to Florence Tamagne, a French historian specialised in homosexuality and its cultural representations, Paris was also the European centre of LGBT culture, characterised by a hedonistic spirit and bohemian lifestyle that opened the doors to sexual experimentation and new, non-heteronormative forms of eroticism. In short, Paris became what we might call “the European pleasure capital” and a great many salons, bars, bathhouses and clubs – especially around Montmartre and Les Halles – that embraced and developed this new LGBT culture sprang up in a relatively underground but accessible scene.

Twentieth century. Paris continued to be the capital of freedom until the outbreak of the First World War. Another example of these new spaces was the literary salon run by Natalie Clifford Barney, an openly lesbian American writer and poet based in the French capital. Barney hosted the salon for more than 60 years, holding meetings where her guests could socialise and discuss literature, art, music and other interesting matters. Joan Schenkar, a famous contemporary writer and playwright born in Seattle and known for her works based on women’s lives, described Barney’s salon as “a place where lesbian assignations and appointments with academics could coexist in a kind of cheerful, cross-pollinating, cognitive dissonance”. Indeed, beginning in the late nineteenth century, relationships between women became much more visible in Paris, which, to quote the scholar Catherine Van Casselear, became “the undisputed capital of world lesbianism”.

But not everyone welcomed the city’s new idiosyncrasy. Indeed, the conservative sector condemned it, calling for order and describing Paris as the “New Babylon”. Although Berlin took over as the homosexual capital of Europe in the interwar period, Paris continued to be an interesting hub of LGBT leisure and social activities and culture.

This process of gaining visibility and demanding freedoms was fatally dashed by the Nazi occupation of France: the places that promoted LGBT culture were closed down and homosexuality was established as an offence punishable by the law, ushering in one of the harshest and gloomiest periods for the LGBT community in France.

In contrast to the festive and comic tradition of Hercules in drag that was used by artists and writers from Ovid to Rubens to signify the excesses of love, we also find a moralising interpretation of Hercules in the oeuvre of Seneca and Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia: or, Moral Emblems, which is the one Hans Cranach uses in this work.

The abovementioned episode of Hercules at the court of Omphale, one of the most popular in the Renaissance, is thus used by Cranach as a misogynous and moralistic warning against women who exercise authority, as they can cause men to take leave of their senses.

Cranach’s work shows Hercules sitting on what appears to be a wooden bench, surrounded by three women of the court. The hero, known for his strength, is radically subjugated to female norms. All three figures have been interpreted as ladies-in-waiting to the queen, as none of them wears distinctive clothing.

Cranach places the hero in the foreground. Two of the women flank the demigod, while the third, standing with a spindle in her hand, frames the composition on the right and engages the spectator with her gaze. According to the story, one the two women near Hercules was entrusted with dressing him as a woman, which is why she has placed a bonnet on his head, and the other with teaching him to spin, which is why she is helping him wind the yarn. The expression of amusement on their faces contrasts with his own – a mixture of resignation and embarrassment. Hans set the scene in a contemporary context by attiring the figures as ladies of the German court in rich velvet dresses and headdresses with gauze veils.

Continúa en la planta baja

On the map you can see the rooms where the masterworks are located.

The Birth of Venus (The Aurore)

This piece is a combination of three motifs from plaster casts Rodin had created two decades earlier. The crouching woman was a solitary figure that did not look anywhere, and the standing figure was originally in a horizontal position.

The resulting composition is a pair of naked women engaged in an intensely intimate moment. Their hairstyles, which seem to echo the female fashion of the period, lead us to view them as two real women despite the mythological allusions of the title. The standing figure unashamedly shows her pubis – or mount of Venus – underlining the homosexual relationship between the women as opposed to the sensuality or sexuality of a distant goddess.

She raises her arms and appears to gather her hair in a gesture that can be interpreted as giving herself over to ecstasy with a member of the same sex. Rodin’s interest in lesbianism was consonant with a general interest in this theme among the artistic bohemia that arose in the late nineteenth century. It sprang from the fin-de-siècle decadent movement’s exploration of other forms of love as well as from the greater social visibility of lesbianism, which was particularly pronounced in the Paris art circles. This interest can also be detected in the paintings of Courbet (Sleep, 1866), Félicien Rops (Sappho, 1890) and Klimt (Water Serpents, 1907 or The Girlfriends, 1917) as well as in the poetry of Baudelaire, who devoted a poem to lesbians entitled ‘Damned Women’ in The Flowers of Evil, whose publication caused a huge scandal and led to the work being censored.

Whereas, as Walter Benjamin stated, Baudelaire transformed lesbians into modern heroines, Rodin transformed the verses of the accursed poet into drawings in a commission executed between 1887 and 1888 in which he paid special attention to the prohibited poems. From this point onwards, he continued to explore lesbian themes in personal drawings and sketches as well as in sculptures, prominent among which are the Metamorphoses of Ovid of 1884 for the famous Gates of Hell. Rodin had planned to represent different types of love on these gates, but the classical pretext of the Metamorphoses made it less scandalous and connected the theme of passion with Ovid’s conception of it as an incurable illness.

In private commissions such as Iris awakening a Nymph or Condemned Women, Rodin could be erotically more explicit or, if preferred, realistic, as he was known in Paris for using lesbians as models for these works. For Condemned Women Rodin is reported to have hired two lesbian dancers from the Paris Opera whom Degas had introduced to him.

This series of sculptures is part of a large collection of works that are notable for large the number of sketches – a voyeur’s portraits of a female body in explicit poses, masturbating or engaging in sexual relations with other women. They were works created by a gaze which, although erotic, was not intended to excite or pass moral judgement. But his gaze was that of an artist of his era, since, as Barbara Creed explains, these works reflected a series of stereotypical views of lesbians as narcissistic women. In fin-de-siècle painting of the day lesbian relations were viewed as an extension of narcissistic desires, which is why in many works of the period the two women were depicted with the same face, hairstyle and clothing.

Tour resources

The order of the works in this pdf may differ from the recommended order.